The Georgian Theatre Royal

Nicholas Allen

|

|

| (Photo: Cloud Nine Photography) |

The Georgian Theatre in Richmond, North Yorkshire has been authoritatively described as the most important theatre in the development of the English playhouse. It is listed Grade I and built of rubblestone sandstone with a graded stone slate roof, originally pegged with sheep bones. The building's physical massing and impact on the streetscape is relatively low key, and its external appearance is non-specific, providing no true indication of its function. Simply styled in the local vernacular, it blends with the many late 18th century buildings in the centre of town.

Britain has only four pre-1830 theatres which retain the form and style of their original auditorium and stage and, of these, Richmond is by far the least altered, leaving it as the most complete and earliest example of a small provincial Georgian playhouse. (Only the much altered Theatre Royal Bristol, 1766, is older).

It was built in 1788 by Samuel Butler on land leased from Richmond Corporation as one of his circuit of theatres, and his company staged regular productions here until 1830 when the corporation refused to renew the lease. Nevertheless, the playhouse continued to be used for occasional theatrical performances until 1848 when the pit was floored over and wine vaults constructed. Above stage level the playhouse became an auction room, but fortunately the boxes and gallery were not disturbed and, when re-discovered in the late 1930s, the rest of the interior was found to have survived virtually intact.

|

|

| The theatre as it appears now (top) and as it appeared at the start of the project (above), with its intrusive stage lighting, ventilation fittings, and rather garish decorative scheme. Wherever practical the new decorative scheme was based on evidence uncovered in the investigation of the surviving original fabric. Some elements, including the front cloth and light fittings, were based on contemporary 18th century designs. |

In 1963, over a century after the last performance was held here, the old theatre was reopened following a restoration led by the theatre consultant Richard Southern. However, the restoration was limited by lack of money and by the fact that Southern's research with Richard Leacroft into the Georgian playhouse had only just begun. Since then, significant additional scholarly research has been undertaken, discoveries have come to light and knowledge has been assimilated, providing vital information for further restoration.

The most recent programme of work commenced in 2003. Throughout the process emphasis was placed on the need to sustain this building in its primary function as a working theatre. This required a fine balance between parts of the building (particularly the later additions) which required a re-evaluation for modern use, and other areas where there was a need for them to be returned to a former state.

Loss of detail and fabric has occurred over the years and recent research and discoveries informed the new programme, proving invaluable in areas where knowledge was lacking at the time of Southern's restoration. Physically small but nevertheless significant losses within the theatre include the original proscenium doors, original stage machinery, methods of lighting and ventilation, as well as most of the original paint layers within the auditorium.

The project included the design of a new three-storey 'front of house' containing a stairwell and lift, toilets and two bars. This was designed as a contemporary interpretation of the basic form and mass of the original, and one that allowed the legibility of the 1788 theatre to shine through. Relatively little was done to the original external structural fabric, which was basically sound, other than to underpin part of the south wall, found to be lacking a foundation during the demolition of various 20th century additions. From a conservation perspective, the most interesting element of the project is the approach to the interior refurbishment of the 1788 auditorium and stagehouse.

DECORATION

|

| The ceiling of the auditorium is now painted with white clouds in the manner of the 18th century, and has new ventilation grilles. (Photo: Cloud Nine Photography) |

There is no primary evidence to indicate how the theatre was decorated or lit in 1788 beyond the lower levels of painted decoration indicated in the microscopic paint analysis carried out in the early stages of the recent works. However, this very comprehensive and thorough examination, carried out by historic paint analyst Lisa Oestreicher, proved vital in providing the basic evidence used in developing an authentic decorative scheme, and while it provided information on the sequence of colour schemes, in this instance the paint constituents used did not enable accurate dating.

Furthermore there are no accounts of the decoration of the Richmond Theatre in newspapers or diaries, and secondary evidence for the decoration of 18th century playhouses in general is also minimal. A decision had to be made on a date for a decorative scheme that could be supported by the primary and secondary evidence, and 1816 as a date had many attractions, not least because there is a wealth of secondary evidence for the decoration and lighting of late Georgian playhouses between 1800 and 1830 including:

- The watercolours of Robert B Schnebbelie (1780-1849) which reveal in great detail the architecture and audience of minor theatres in use between 1819 and 1825.

- The 'Eyre manuscript', an unpublished account of the development of the Theatre Royal Ipswich from 1803 to 1888 illustrated with watercolours and scraps of original wallpaper.

- Studies of the remaining fragments of other Butler theatres, especially Harrogate, for which accounts survive.

This primary and secondary evidence was brought together by scenic artist Pauline Knox-Crichton in discussions with expert theatre and other consultants to create a decorative scheme that is both historically authentic and attractive to modern audiences. The scheme builds on a background of stone/beige to the walls and perimeter of the ceiling, with the joinery work (doors, columns, box dividers, and box fronts) painted a blue/green. The floors have all been left as natural wood.

|

| A photograph of the interior taken in 1944 by Richard Leacroft shows the theatre when still being used as an auction house, with the pit floor covered over. |

In 1963 the rubblestone forming the rear walls to the side boxes was covered in canvas and painted. Although inspection revealed that the stone had been painted in the 18th century, little paint now remains, and evidence indicated that canvas on battens had been installed early in the theatre's life. It was therefore decided to continue this tradition, and painted canvas linings have now been reinstated.

In common with many playhouses of the period, the ceiling has been painted with a sky of white clouds on a blue background, within a border that mirrors the line of the box fronts. While this was commonplace at the time, it required the remodelling of the theatre ceiling at the point where it sloped upwards towards the rear of the auditorium. However, firm evidence that this was the original ceiling form was found in the ghosted plaster line of the original on the flanking walls, and confirmed by the position of a now partially exposed roof truss coinciding with what we believed to be the original ceiling line.

Miraculously, several of the 1788 timber painted panels (the stage left box front, and two above the proscenium doors) have survived, and were expertly restored in the mid 1990s. The stage left box front shows the shield of the Borough of Richmond, and opposite, the shield of Thomas Dundas, one of the theatre's original patrons, has been reinstated, the original having been lost in a small fire in the 1940s. Over the centre box are the reproduced Royal Arms of George III known to have been introduced when the 'Theatre' became the 'Theatre Royal'. The rest of the box fronts have been painted with a simple swag motif in dark green on the blue background, with the names of prominent playwrights painted over the boxes in the style of the 'Shakespeare' box, which is the only original to have survived.

THE STAGEHOUSE

|

|

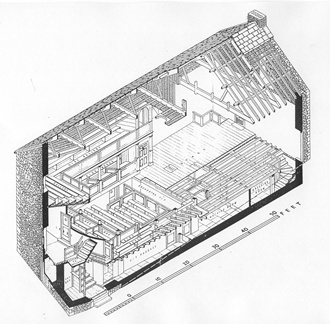

Reconstruction by Richard Leacroft of the original theatre

design (from The Development of the English Playhouse

by R Leacroft, Methuen 1973) |

None of the original stage surface survived the conversion into a wine vault after the theatre closed in 1848 although many of the structural timbers did survive and have been retained in situ. However, these had deflected over the years and had subsequently been propped, resulting in a bowed and uneven raked stage. New structural timber joists were inserted including an oak flitch beam to support the front of the stage, and adjustments were made to ensure as even a rake as possible.

The 1788 trap sliders and the trimmers for the grave trap had also survived, and have been retained in situ beneath the new red deal stage, within which fast-rise trap doors and one fast-rise trap have been installed so that the stage effects used by Butler's company and others can be recreated.

The question of how far the stage extended was the subject of much debate, and within the documentation which already exists on the layout and form of the Richmond playhouse, much time has been devoted to the original position of the forestage. Research now shows that the original forestage extended to the first column, making the pit a perfect square and extending the acting area into the house by about 1.6 m (5' 3") and that this was cut back in the 19th century. A permanent flexible forestage has now been built, replacing the temporary arrangement introduced in 1963.

The current layout of the stage at Richmond provides for two possible stage formats; a stage front immediately downstage of the proscenium doors, or a forestage to be added by inserting a number of 'drop-in lids' to form a cover over the small orchestra pit. One expert, Mark Howell, has taken issue with the existence of the orchestra pit, saying that he knew of 'no evidence that 18th century provincial theatres ever incorporated orchestra pits'.

This issue of the Georgian orchestra pit illustrates perfectly the way in which the conservation philosophy needs to be tailored. While the debate about the existence of an orchestra pit is an interesting one, the reality of operating the playhouse today demands that one must be provided. The question is therefore one of carefully considered design which respects and acknowledges the forestage of a provincial Georgian playhouse and also recognises the need for a practical operational orchestra pit.

|

| The introduction of a new ‘front of house’ to contain two bars, toilets, staircase and a lift avoided the need for extensive alterations in the original theatre (the second gable). |

The previous restoration of the playhouse took place over a long period and in the early phases involved both Richard Southern and Richard Leacroft, although the latter played little part in the major restoration work in 1962. This early work included the re-interpretation of the physical structure, and in particular the wine cellar vaulting which lay beneath the stage and auditorium pit. As part of this process it is clear from Richard Leacroft's proposal drawings for the pit layout (produced in 1949) that a new wall was constructed to support the front of the stage (not the forestage). This provided:

- a rear wall to the orchestra pit

- a structural wall for supporting the front of the stage

- acoustic separation between the dressing rooms/machine cellar etc

- some fire separation between the sub-stage and the auditorium.

The concept of a formal structural wall separating sub-stage from auditorium is in reality a late-Victorian concept, not at all Georgian in origin, and superseded what was generally only a wooden partition.

The evidence provided by Leacroft's drawings and further evidence recorded during an examination of the theatre by a local school teacher in 1939 has allowed greater clarity to be brought to the layout of the sub-stage, which almost certainly extended under the forestage in 1788.

It was decided therefore to remove the 1963 proscenium sub-stage wall, which had little relevance to the original layout of the playhouse, and to replace it with heavy timber sliding doors, allowing either a larger orchestra to be accommodated in the pit, or with the forestage in position, additional dressing room space in the machine room which is sometimes needed, albeit on an ad hoc basis. Large drawers were also provided which slide under the pit floor to give much needed additional storage space.

FLY FLOORS

The 1963 horizontally set fly floors have been replaced. Built in red deal, they now follow the slope of the stage as they did in 1788, allowing painted stage set panels of a uniform height to be slid into place on stage using scene runners, or grooves, which have also been re-introduced.

These allow the authentic recreation of late 18th and early 19th century theatre using a facsimile of Britain's oldest set of scenery, The Woodland Scene, which Richmond was fortunate to be lent in 1963. The original, which was probably painted between 1818 and 1836, now resides in the theatre's museum as it is too valuable to use on stage.

THE LIGHTING AND VENTILATION OF THE AUDITORIUM

There is no primary evidence of the original lighting, which will have been by candle since gas was not available in Richmond until well after the theatre's closure. Whether or not oil fittings were installed later in the theatre's history, it is reasonable to suppose that glass chimneys were introduced here as elsewhere early in the 19th century to steady the fluttering flame of the new wax candles which were more efficient than the older tallow candles.

In the 1963 restoration the principal 'period' lighting was by artificial candles bracketed off the columns. These were elegant in a domestic way but never seemed appropriate to a public playhouse. They also provided little light and the result was that they appeared to be no more than decoration.

New 'candles' have been introduced in the auditorium and increased in number from 16 to 54, each set in a glass chimney supported by a cast iron fitting. From above each column small iron rings are hung from brackets to a design derived from those shown in the Eyre manuscript and in Thomas Rowlandson's watercolour of the Scarborough Theatre of 1813, while the remainder are suspended on large iron rings from the ceiling, one in a central position and two slightly smaller ones over the forestage.

|

The original painted panel of the Sheridan box with a shield

|

When examined in the 1950s, several circular openings in the ceiling were discovered, including one over the central forestage, plastered over in the 19th century. Secondary evidence indicates that these provided extract ventilation assisted by the stack effect of warm air rising from the candle rings suspended below them. These have now been recombined with black iron grilles to provide fresh air input, and candle rings have been suspended from them on retractable cables so that they can be raised above the audience sight lines during performance.

All the candles have random flicker and provide as realistic an impression of 18th century lighting as modern technology allows, and lighting in the ceiling to the boxes has also been introduced by way of threading fibre optics above the 1788 sloping plaster ceiling. Virtually invisible during performances, this lighting is sufficient to enable patrons to find their seats and to read their programmes.

STAGE LIGHTING IN THE AUDITORIUM

The necessary introduction of modern stage lighting had resulted in an unsatisfactory intrusion of heavy-looking black stage luminaires, hanging from lighting rails that drew the eye and bore no relation to the architecture of the auditorium. These have been replaced with new, much smaller luminaires, finished in the same background colour as the ceiling, and hung from lighting rails that mirror the line of the box fronts and perimeter of the new painted ceiling, resulting in a greatly reduced level of visual intrusion.

THE SEATING

The re-created 1788 benches, installed in 1963, have been re-introduced with new detachable cushions, detachable backs, and removable bench ends designed to extend the benches over the aisles as done in 1788. In the boxes the early 20th century gilt ballroom chairs have been replaced with new chairs to a less intrusive 18th century pattern. No great improvements in comfort have been made in the auditorium, although elsewhere in the new extension are greatly improved bars and lavatories.

THE PROSCENIUM ARCH AND DOORS

The oddly square-headed proscenium 'arch' was also modified. Inspection of the building fabric and study of secondary evidence suggested that a 3-point arch had been removed when the theatre became an auction room in the 19th century. Evidence has recently been found for the hanging of a detachable painted pelmet immediately behind it. Both have now been reintroduced, completing the proscenium.

Perhaps the greatest change is the replacement of a bulky four-panel reefer curtain of bottle green by a 5-panel less full reefer curtain of plum baize, a colour in widespread use at the beginning of the 19th century. This is capable of being hauled up out of view.

However, pride of place goes to the recreated front cloth. Front cloths, which depicted a local scene, were a familiar integral part of the decorations of many theatres in Britain and North America for the whole of the 19th century. These front cloths greeted the audience on arrival and helped raise their expectations. The reefer curtain would be used only at the end of a performance or, if any, at the interval, between mainpiece and afterpiece of a long evening's programme.

Front cloths were generally roller cloths. The bottom of the cloth was attached to a six-inch wooden drum on which the cloth rolled upwards to reveal the scene and the actors.

There is no primary evidence as to what was painted on the Richmond front cloth but there is evidence that a local Royal Academician, George Cuit the elder (1743-1818) created painted scenery for the opening of the theatre in 1788, and it was therefore decided to reproduce on the front cloth a view of Richmond Castle and the River Swale, painted by Cuit in 1810. This was painted by Pauline Knox-Crichton and Peter Crombie.

Only at Richmond is the earthy immediacy of the Georgian playhouse strongly evoked. But the theatre has another role beyond being a living museum for both the British and the international theatre community. It has an equally significant role as the community theatre of Richmond and the surrounding area. The recently completed work will hopefully ensure that it succeeds in its latter role, without which it cannot survive to perform the first.