Heritage Protection In Brief

Jonathan Taylor

|

Figure 1 The Café Royal, Edinburgh (1863, listed category A) |

The current system which protects the historic environment in England and Wales is under review. Developments here are being watched closely by politicians in Scotland and Northern Ireland, and any changes may well be copied by the rest of the United Kingdom.

Throughout the UK, protection of the historic environment is effected by the designation of listed buildings, conservation areas and scheduled ancient monuments. Under these schemes, buildings and structures are protected by law, and carrying out work without the appropriate consent can be a criminal offence, leading to a fine and even a prison sentence.

Although some grants are available for the management and maintenance of scheduled monuments, grants are not generally made for the conservation and repair of listed buildings. Their protection is firmly based on the stick rather than the carrot. The government is coming under considerable pressure to at least introduce reduced rates of VAT for conservation and repair work, but it is likely that the principle of the stick will be maintained, with modifications focussing on simplifying the existing system, greater openness, and, for certain listed buildings, the development of tailored agreements or management plans which will avoid the need to apply for consent to carry out certain types of alterations.

LISTED

BUILDINGS

A ‘listed’

building is one which has been entered onto the statutory list of buildings

of ‘special architectural or historic interest’. These buildings are protected

by law from demolition, or alteration. The system of legislation and government

guidance which protects them is designed to control change rather than

to prevent it, since almost all buildings need to be adapted to accommodate

new requirements from time to time. A special permit known as ‘listed

building consent’ must therefore be obtained from the local planning authority

(usually the district, borough or city council) for all alterations –

inside or out – in much the same manner as planning permission. Indeed,

it is a criminal offence to alter any aspect of one in a manner which

affects its character as a listed building without this consent. In theory,

like-for-like repairs do not require consent, since they do not effect

an alteration. However, most repairs do entail some degree of alteration,

so it is always best to consult the local planning authority before commencing

any work.

|

Figure 2 Inside the Café Royal with its magnificent interior with Doulton tiled murals (added 1886) |

‘Listed building consent’ is also required for alterations to any structure within its grounds or ‘curtilage’ which was built before 1 July 1948.

In the event of a refusal or an enforcement, an applicant can lodge an appeal with either the Planning Inspectorate (England or Wales) or the Inquiry Reporters’ Unit of the Scottish Executive. The appeal is made to the relevant government minister, but they are almost invariably conducted and determined by an inspector appointed by that minister.

Alterations to some places of worship fall outside this system of control, as the main churches enjoy what is known as ‘ecclesiastical exemption’. This exemption is limited to the church bodies which operate ‘an approved system of control’. In England and Wales all alterations requiring listed building or conservation area consent may be dealt with through this system, provided that they affect a listed building which remains in use as a place of worship (including cathedrals, churches and chapels). In Scotland the exemption is limited to interior alterations only.

The list includes approximately 440,000 entries, but as some list entries include several buildings at the same address, the total number of listed buildings is larger – perhaps 600,000. The listings are graded according to the architectural or historic importance of each building, Grade I being the most important in England and Wales and category A the most important in Scotland. Other grades are II* and II in England and Wales or B and C in Scotland. The grade or category generally reflects the age and rarity of the building, but many other factors are also taken into account, such as technological innovation, townscape value or connection with a particular historical event. Approximately 92 per cent of listed buildings in England and Wales are listed as Grade II.

Although most proposals for listings come from the various local and national government bodies, anyone can propose a building for listing. Under the present system the proposal is considered in private by the relevant government department (DCMS, Scottish Assembly or Welsh Assembly) with the advice of specialists at either Cadw (in Wales), English Heritage or Historic Scotland, and the addition is then made or turned down by the appointed government minister. As there have been cases where an owner has got wind of a proposal to list the building and has taken pre-emptive action, knocking it down before the listing came into force, there is also an emergency procedure known as ‘spot listing’. Under this procedure, full protection is immediately conferred on the building without having to wait for a decision from the government minister responsible. If the listing is not subsequently confirmed, and the building owner suffers a financial loss as a result, compensation may be payable. However, the lack of any public consultation is, in the opinion of the government, unacceptable, and so the system may have to change.

Each building is described briefly in its list entry. The description generally outlines aspects of special historic or architectural interest, but it should not be relied on as a comprehensive guide to why the building is important, as most listings are made without a thorough survey of the building. (There have been a few well-reported cases where new buildings have been built from reclaimed material to look old, and have been listed. But such mistakes are extremely rare, and it is generally accepted that this approach is cost-effective and sufficiently reliable.) Once listed, protection is conferred on all aspects of the building, whether mentioned in the list description or not, including its important features and its later alterations.

CONSERVATION AREAS

|

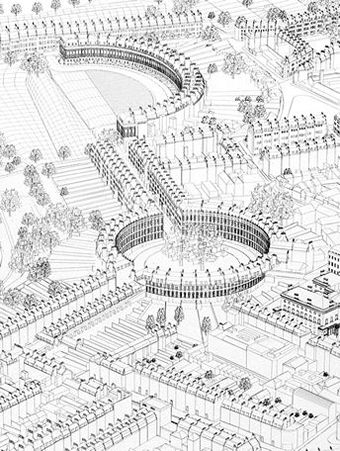

| Figure 3 A computer generated model of part of the city of Bath, illustrating how spaces and spatial relationships as well as buildings define the character of conservation areas. The Royal Crescent is at the top with the King’s Circus below. (Image: CASA, Bath University) |

Conservation and heritage protection tend to focus on buildings – particularly the larger and more historic ones. However, it should not be forgotten that the places we most enjoy are often the product of the inter-relationship between many different buildings, the surfaces and structures between them, and the trees, shrubs, climbing plants, hedges and lawns with which they form an integral whole. The historic environment is composed of both landscapes and townscapes, as well as all their component parts. A street, for example, may gain its character from the width, height and scale of the space between the buildings, from the shopfronts and signage, from the paving, street lamps, railings and other hard landscape features and finishes, and from trees, hedges and other soft landscape features, as much as from the buildings themselves.

Although the principal form of protection in the historic environment is through the listing of buildings and the scheduling of monuments, the designation of conservation areas also brings some limited protection, principally from demolition. Some additional protection is given to trees in a conservation area, bringing the demolition of all buildings into control. In addition, the local authority can also introduce Article 4 designations to control specific alterations to houses which would otherwise be automatically approved under permitted development rights’. Such alterations could include the replacement of traditional windows and doors with unsuitable uPVC products.

Local authorities are required under the Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas) Act 1990 to designate as conservation areas any area ‘of special architectural or historic interest’ with a character or appearance which merits preservation or enhancement.

There are approximately 10,000 conservation areas in the UK, and the range is vast. Usually buildings or townscapes form the focus, but often they include garden and landscape settings. In some cases conservation areas include development sites and other places which detract from the setting of an historic core, drawing attention to their importance and to promote their enhancement.

SCHEDULED ANCIENT MONUMENTS

|

| Figure 4 West Kennet Long Chambered Barrow, Wiltshire, a classic example of a scheduled ancient monument |

A wide variety of archaeological sites, monuments and structures ranging from standing stones to industrial sites and World War II pill boxes are protected as scheduled ancient monuments (SAMs). The main differences between these sites and listed buildings are that SAMs generally do not have a viable use, and under the Ancient Monuments and Archaeological Areas Act 1979 all works to them (not just alterations) require special consent – in this case ‘scheduled monuments consent’. Again, transgressing the law can lead to a criminal conviction and a fine. In this case, it is a criminal offence to damage a scheduled ancient monument either deliberately, recklessly, or by carrying out work without the appropriate consent. It is also a criminal offence to use a metal detector on one or to remove an object from one without a license.

There are currently around 30,000 SAMs in the UK, and the number is growing rapidly as English Heritage, Cadw and Historic Scotland are engaged in new programmes to reassess all known sites – 600,000 in England alone. Only those of ‘national importance’ may be scheduled, and then only if scheduling is considered to be the best means of protecting them. Historic buildings and standing structures which are usable or could be made usable are more likely to be listed.

CURRENT

HISTORIC BUILDING LEGISLATION

In England and Wales the main legal requirements affecting the conservation of historic buildings are set out in the Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas) Act 1990. In Scotland the equivalent Act is the Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas) (Scotland) Act 1997.

These two acts are supplemented by various government guidance including, in England, Planning Policy Guidance Note 15: Planning and the Historic Environment. (PPG15 as it is commonly known, is to be combined with PPG16, which covers archaeology, and reissued in a new format by the Office of the Deputy Prime Minister.) Equivalent documents for Wales are the Welsh Office Circulars 61/96 and 1/98 Planning and the Historic Environment, and for Scotland the equivalent is the Memorandum of Guidance on Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas. These documents guide local planning authorities in their decision-making, and are used to interpret planning law.

…no person shall

execute or cause to be executed any works for the demolition or alteration

of a listed building or for its alteration or extension in any manner

which would affect its character as a building of special architectural

or historic interest unless the works are authorised.

Section 7, Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas) Act 1990

Applicants are also required to take into account the policies set down by the local planning authority for conservation and more general planning issues. Many produce extremely useful guidance on their conservation areas and the features which must be preserved. They may include requirements for common developments, such as roof extensions, sometimes specific to individual buildings or terraces.

In addition to specific protection regimes, all historic buildings are also subject to ordinary planning controls and the requirements for planning permission under The Town and Country Planning Act. They are also affected by the Building Regulations.

RECOMMENDED READING

- Mynors, Charles; Listed Buildings, Conservation Areas and Monuments, Third Edition. Sweet and Maxwell, 1999

GOVERNMENT GUIDENCE

- England: Planning Policy Guidance Note 15: Planning and the Historic Environment and Planning Policy Guidance Note 16: Archaeology and Planning

- Wales: 61/96 Planning and the Historic Environment: Historic Buildings and Conservation Areas 1/98 Planning and the Historic Environment: Directions by the Secretary of State for Wales

- Scotland: Memorandum of Guidance on Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas