Historic Window Glass

Michael Brückner

.jpg) |

.jpg) |

Fig 1. The Merode Altarpiece by the Master of Flémalle around 1425: on the left the window of a relatively wealthy family is shown with glazing in the small fixed lights at the top, while the unglazed lights below are closed with wooden shutters alone, as are the windows of the craftsman’s workshop on the right. (Photo: Metropolitan Museum, New York) |

We tend to take the use of flat glass panes for sealing window openings for granted, but for many applications glass used to be unaffordable. Animal skins and other translucent materials were still widely used as substitutes for glass in windows until industrialisation gradually reduced the costs. Historical documents from the 18th century describe how complex it was to process the thinly shaved animal skins required, illustrating just how valuable glazing must have been then.

One of the earliest paintings that shows how glazing was used is the Merode Altarpiece which was created around 1425 by the Master of Flémalle. The triptych brings the story of the Annunciation into contemporary scenes of everyday life in the Netherlands.

In the central panel the Virgin Mary sits in a relatively prosperous domestic interior lit by a window with glazing in the upper lights only: the lower lights are unglazed, closed only by the casement shutters (Fig 1). Next door, Joseph is depicted in his workshop with shutters alone. By the time this was painted, fully transparent glass panes had been available for several centuries, but glass was generally unaffordable even for wealthy families, so its use remained restricted to the most important buildings, especially churches.

The production of flat glass with firepolished surfaces on both sides was made possible thanks to the development of glassblowing from about the 2nd century AD. In comparison to the cast glasses available until then, this was a substantial step forward in terms of both quality and technology. Instead of pouring the hot, viscous glass mass on a flat, fireproof surface and spreading it as evenly as possible to form a flat glass panel (Fig 2), the new technology took a detour, creating a hollow body as an intermediate step. For this purpose, a certain quantity of hot glass is picked up by the tip of the blowpipe, by simultaneously turning and blowing with the mouth, and shaping the hot glass with the help of wooden moulds into an elongated balloon. Opened on both sides, a hollow cylinder is created, and once cool it is cut longitudinally and then heated up again so it can be unfolded and flattened (Fig 3). The result is a flat glass panel with a slightly uneven and distorted surface. Trapped air bubbles and fine streaks are characteristic features of this handmade flat glass called ‘mouth-blown cylinder glass’.

|

|

|

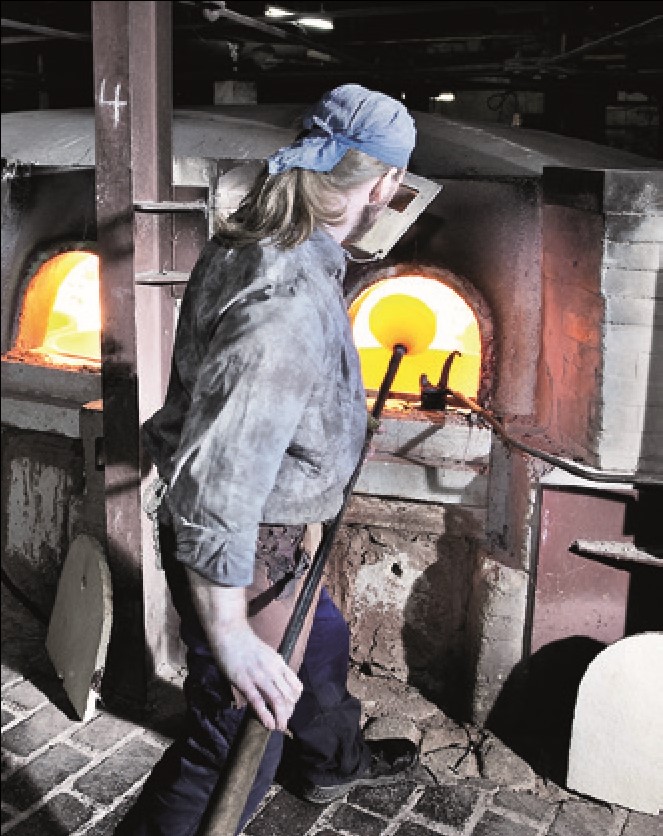

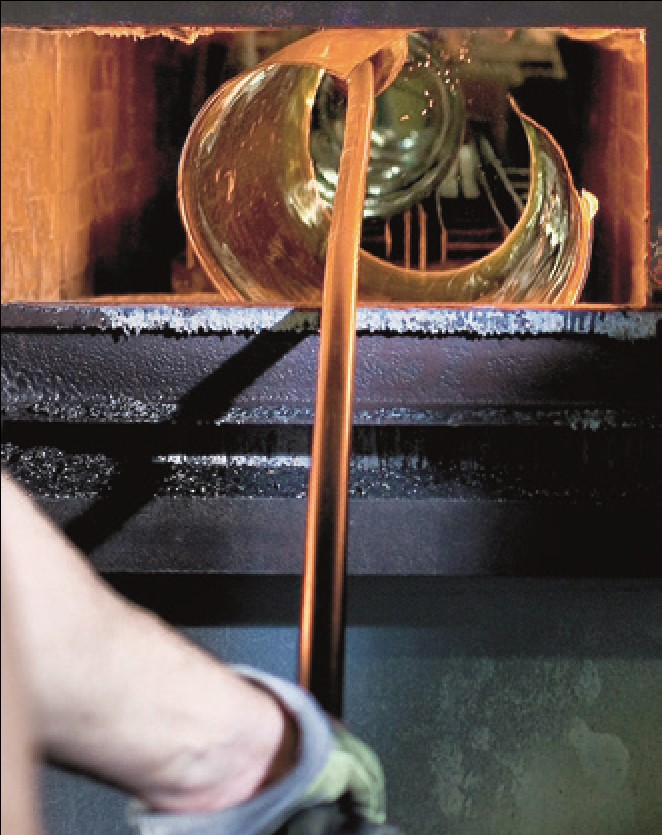

| Fig 3. Making mouth-blown flat glass (cylinder glass): left, picking up the viscous glass mass onto the blowpipe; centre, the elongated glass balloon is formed by simultaneously turning and blowing; and right, after being reheated, the cylinder is cut lengthwise, opened and flattened to create the flat glass panel. (All photos: Glashütte Lamberts) | ||

A variation of this method which was widely used in Britain is the so called ‘crown glass’. The technique produces a particularly large flat disc with a partly sharp-edged stub in the centre, the ‘crown’ (Fig 4). The first step in the process is to blow and shape a glass sphere which is then transferred to a metal rod on the opposite side, and the blow pipe is knocked off, leaving an opening. The sphere is then heated once again. Through fast rotation of the rod in front of the fire, the glass sphere is opened out and extended by the centrifugal force to form a flat disc. Small rectangular or diamond-shaped panes could then be cut from this disk for use as window glass in lattice windows. Although the remaining middle piece is obscured by the stub, it still lets in light and was occasionally used to save money.

|

|

| Fig 2. The production of hand-cast flat glass (Glashütte Lamberts’ table cathedral glass); the underside has a pronounced texture from contact with the table which is typical of cast glass. (Photo: Glashütte Lamberts) | Fig 4. Crown glass with typical concentric ripples around a partly sharp-edged stub in the centre (Photo: Glashütte Lamberts) |

At the end of the 17th century another technique began to develop in parallel to the mouth-blown technique. Hand casting could produce far larger panes of glass, but the glass was not clear because one side was textured. Now, with improvements in grinding and polishing techniques, larger sizes of completely transparent flat glass could be produced, free from distortion. However, the process was extremely laborious and even more expensive than mouth-blown window glass. These ground and polished cast glass panes were mainly used for mirrors in palaces and stately homes, but in some cases also as glazing where customers demanded bigger windows without glazing bars or lead cames.

|

|

| Fig 5. The 18th-century orangery at Schloss Hof near Vienna: the glazing was restored using slightly greenish mouth-blown window glass made to match fragments of the original. | Fig 6. A leaded light windows in the Quaker meeting house at Come to Good, Cornwall which was built in 1710: the small panes or ‘quarries’ are heavily seeded and may include some of the original glass (Photo: Jonathan Taylor) |

Although highly transparent glass surfaces were achievable with more or less effort in the techniques described above, completely colourless window glass in any size remained rare for many centuries. Both the procurement of raw materials and the firing technology played crucial roles in this respect.

Quartz sand, soda and lime, the basic components of clear glass, are abundant almost everywhere, but naturally occurring forms are rarely pure. Contaminants can affect the stability and amount of colour in the glass which can lead to very different qualities depending on the region. A light tint of green in the glass, caused by ferrous sands, was widespread and a reason for a price reduction. In the 19th century, classification into different purity classes was still usual, and the classes were deliberately employed by builders according to where they were to be used. While the much more expensive crystalclear glass was often used in representative rooms, for outbuildings such as the Orangery at Schloss Hof in Vienna (Fig 5) the greenish ‘forest glass’ was deemed sufficient.

|

| Fig 7. The meeting room in Eidsvoll House, Norway where the Norwegian Constitution was drawn up and signed in 1814: the fine wooden glazing bars were a technological necessity because it would have been impossible to make panes of mouth-blown flat glass large enough to glaze the entire opening. (Photo: Eidsvoll 1814, Guri Dahl) |

Nowadays, raw materials are chemically cleaned, so for restorations, ‘discoloration’ must be specifically introduced into the molten glass. By adding various metal oxides and salts, the most varied colour tones and nuances can be matched.

Besides the need for consistency in colour, transparency and surface composition, it was the format of the glazing which perhaps posed the greatest technical challenges for the early glassworks. To glaze bigger window openings the glass panes, which in early times were much smaller than they are now, had to be trimmed and assembled with lead cames or wooden glazing bars (Figs 6 & 7). Through the centuries constant developments in firing and cooling technology among other improvements, enabled the production of increasingly large flat panes of glass. However, ultimately, the size of mouth-blown glass that can be produced was restricted by the limitations of human performance in terms of lung capacity and physical strength. Only with the development of machine-made flat glass (drawn glass and float glass) in the 20th century could sizes be created that did not depend on physical strength. The subsequent increase in production was substantial, starting a price decline which led to the closing of countless glassworks in the 1920s. As a result, only three glass factories (Fig 8) survive worldwide which continue to produce mouth-blown glass by the traditional methods for use in works of art and heritage conservation.

|

| Fig 8. The production hall of a traditional glass factory that is still operating today where mouth-blown cylinder glass, crown glass and even hand-cast flat glass are all produced using historic techniques (Photo: Glashütte Lamberts) |

References

Mark Spoerer, Adalbert Busl, Heinz W

Krewinkel and Reinhard Holsten: 500 Jahre Flachglas, 1487–1987: von der Waldhütte zum Konzern, Schorndorf 1987

Manfred Mislik, ‘Fensterglas’, Restaurator im Handwerk: the trade magazine for restoration practice, 9th Volume, No 4, Pages 22–25, 2017