The House of Good

Eddie Tulasiewicz

The time given by volunteers in the provision of social and community good in church buildings is valued at £850 million per year.

With national heritage bodies, charitable trusts and foundations facing increasing demands for funding, it is becoming increasingly important for churches to be able to demonstrate, using quantifiable measures, the value of church buildings to local people and to the nation.

That’s why in 2020 the National Churches Trust, working with economic consultants State of Life, carried out a pioneering study into the economic and social value of church buildings.

The findings of our report, The House of Good, have provided us with robust evidence to make the case for funding church buildings to ensure their future.

We hope that in the future we may be able to provide a ‘House of Good’ calculator that will allow individual churches to measure their economic and social value.

The focus of The House of Good study was the UK’s estimated 41,000 churches, chapels and meeting houses that are open for regular worship, excluding cathedrals.

We included activity that may take place within a church hall as an extension of the church building. From a review of the literature and research in this area we concluded that research estimating the monetary valuation of the benefits of church buildings to society is still in its infancy.

Studies tackling the subject are rather scarce and thus far have tended to focus on more traditional, economic spend (revenue, costs) and the heritage and/or tourism value, with some looking at volunteering.

In the report we therefore attempted to fill in this gap with a comprehensive macro-level valuation study of church buildings, covering the key economic and social value components of the vital community activities and social care that church buildings provide and host.

The main data sets we used were the National Churches Trust surveys from 2010 and 2020. To analyse the relationship between church attendance, wellbeing and volunteering at an individual level, we also used 77,510 responses from all areas of the UK from the Understanding Society survey 2009–10 and 2012–13.

The two NCT surveys covered most of the Christian denominations in the UK, and although proportional representation of each denomination (especially the smaller ones) could not be guaranteed, we have reasonable confidence that the study took into account the denominational diversity of Christian churches throughout the UK.

Wellbeing Valuation

A very important component not yet tackled in the literature is the wellbeing benefits generated by church buildings.

This valuation is explicitly recognised in HM Treasury’s The Green Book, the central document in the UK government on how to evaluate the efficacy of a policy and its economic and social value.

This can include benefits to the people attending church services, volunteering within and through the church, or participating in the various community activities at the church.

It also includes the improvements in health and wellbeing of those that the church helps with youth services, mental health support, food banks, and drug and alcohol treatment.

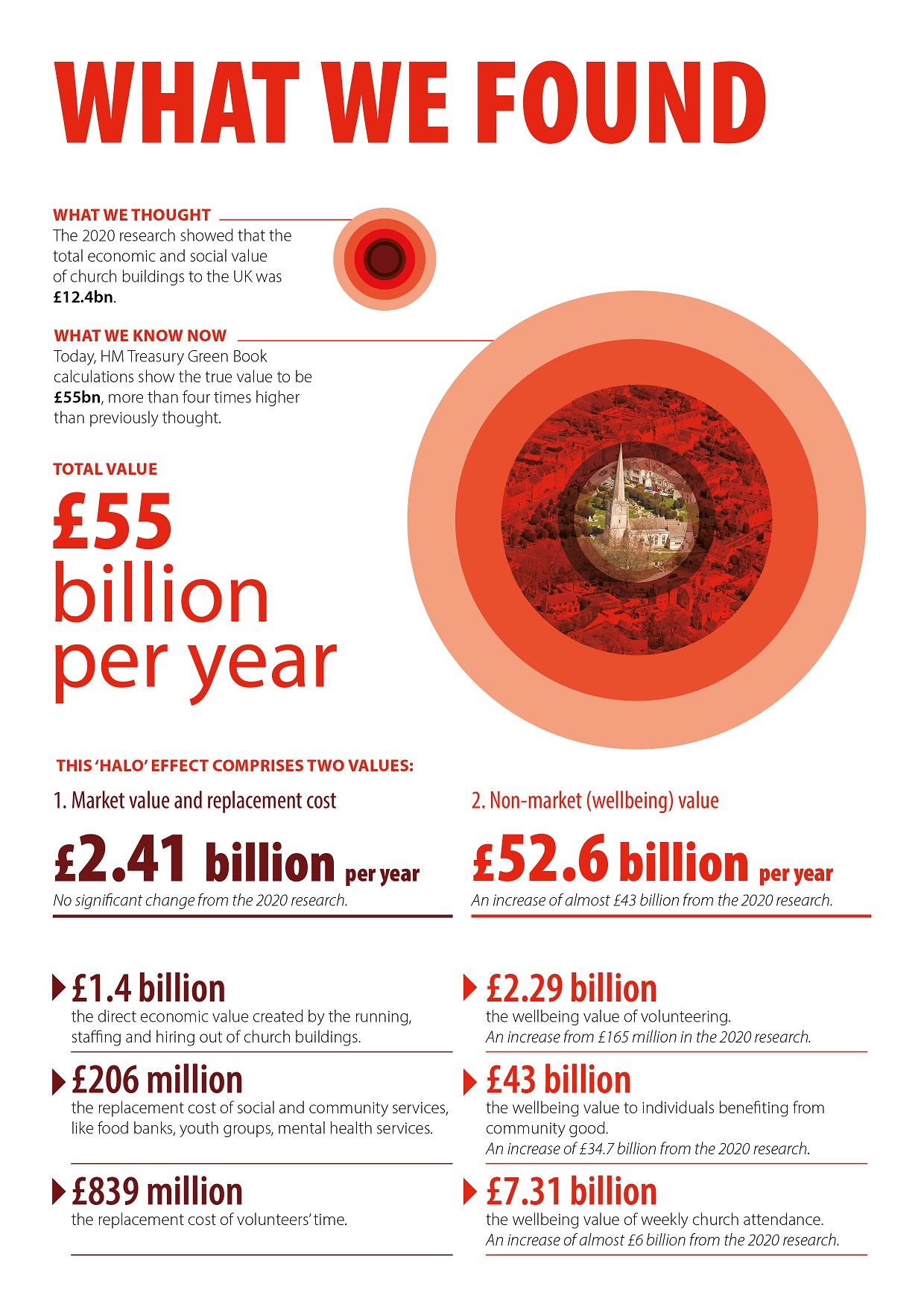

The Halo Effect

|

|

The findings of The House of Good were based on measuring different forms of social and economic value and by analysing both market value and non-market value.

We built up the economic and social value of church buildings in six circles that radiate out from the hub of the church building; we called this ‘the halo effect’.

In total, our report shows that the total annual economic and social value that church buildings generate in the UK is at least £12.4 billion.

This is roughly equal to the total spent by the NHS on mental health in 2018. The economic and social value of an average church in the UK is over £300,000 per year, rising to £1.5 million if less conservative valuation methods are used.

Market Value

The total market value and cost replacement is upwards of £2.4 billion per year. This is made up of three values.

1. Direct economic value: over £1 billion per year

The direct economic value of a church building is created through the day-today work carried out in the buildings and from its upkeep and the value of any investments.

This includes stipends or employment costs for clergy and staff, money spent on maintenance and repairs, running costs such as heating and electricity, donations of money, revenue generated from hiring out the facilities, and tourism-related income.

2. Cost replacement for provision of social good: over £200 million per year

This is the amount local and national government would need to spend to replace the social and community services provided in church buildings. In the study we focused on four key areas of social and community good provided by churches:

(i) counselling and mental health services

(ii) food banks

(iii) youth groups

(iv) drug and alcohol support. These four key areas are important because of the number and scale of these activities in church buildings.

Taken together, these four activities amount to £124 million per year of value generated in direct costs and at least an additional £82 million per year that would need to be found if this social and community good was not able to take place in church buildings.

3. Volunteer economic value: £850 million per year

This is the value of the hours given by volunteers from the congregation and the wider community in the provision of social and community good in church buildings. The time given freely by volunteers is a key element in the provision of social and community good in church buildings.

The data from the National Churches Trust 2020 Survey shows that the average total number of volunteer hours provided per church has grown to 214 per month.

This is almost double the total hours reported in the National Churches Trust’s 2010 Survey. Providing this level of volunteering by staff paid at the National Living Wage (£8.21 an hour since April 2019) would cost local or national government, or other agencies or organisations, £21,080 per volunteer activity at a church or around £850 million per year for all the UK’s churches.

Social Value

The total non-market value (or social value) and wellbeing generated is upwards of £10 billion per year.

|

|

4. Wellbeing value of volunteering to volunteers in church buildings: £165 million per year

I have already presented the potential costs of replacing church volunteers in the provision of social and community good above (£850m). In addition to this value, there are also the health and wellbeing benefits of volunteering to those who volunteer which is valued at £165 million a year.

5. Wellbeing value to the people who benefit from the social and community good made possible through church buildings: at least £8 billion per year

Item 2 outlines the social and community good provided in church buildings via counselling and mental health services, food banks, youth groups and drug and alcohol support. We estimated this to be worth at least £200 million annually in terms of what it would cost to replace these services.

However, church buildings are not distributional hubs of social and community good that exist to save the state money or replace costs.

Rather this good is provided by people’s desire, rooted in faith, to help those in need and to make their lives better by improving their mental and physical health.

This can be defined as wellbeing. At present food banks are by far the most important single social and community good that takes place or is organised in church buildings in terms of their contribution to the welfare of beneficiaries.

The non-market or social value of food banks in terms of their contribution to the welfare of individuals amounts to over £7 billion annually using conservative valuation methods.

The remaining three social activities considered in The House of Good study – mental health services, drug and alcohol support and youth groups – have a combined wellbeing value exceeding £1.3 billion a year. Together, this amounts to an annual total of £8.3 billion. This is equivalent to half the size of the UK care homes sector.

6. Wellbeing value to people from attending services in church buildings: at least £1.4 billion per year

In addition to the vital good that is provided to the community through church buildings, evidence from large national datasets shows that people who attend services in church buildings feel happier and healthier than those who do not attend.

(Note that this value represents the benefit of regular religious attendance and is not necessarily correlated with religious belief.)

Using 2020 church attendance figures, we calculated that the nationwide monetary wellbeing value of regular church attendance in the UK, using conservative valuation method, is £1.4 billion per year (or £604 per person who attends regularly).

The Case for Proper Funding

Despite all the good that is generated in them, church buildings are at risk. If churches cannot remain open because they need repairs to the roof or they do not have basic facilities, they cannot provide these outstanding levels of support.

Although there has been support for church buildings through organisations such as the National Lottery Heritage Fund and through government schemes such as the Listed Places of Worship Roof Repair Fund and the Listed Places of Worship Grant Scheme, no long-term strategic local or national government funding is available.

For its part, in the past ten years the National Churches Trust has awarded over 1,500 grants totalling £14 million to help keep church buildings open but demand far outweighs the ability of the trust to provide grants, and the trust has to turn down 75 per cent of the churches that need support.

Perhaps the most disturbing result of a shortage of funding is that the social value that church buildings provide is often most at risk exactly where it is needed most.

If churches cannot remain open because they need repairs then they cannot provide help. Covid-19 made the need for the social value provided by churches even more important.

Despite church buildings being closed during the lockdown, we found that 89 per cent of churches rapidly re-focussed their efforts to help the community through the pandemic.

Cost-benefit analysis shows that for every £1 invested in church buildings there is a ‘social return on investment’ (SRI) of £3.74 using the most conservative methods, which can go up to £18.10 when alternative wellbeing valuation methods are used.

There is no question that church buildings provide a strong, positive SRI on every £1 invested. Churches are a ready-made, efficient, responsive network of social value and Christian care.

We cannot let these buildings crumble. Not only are churches our heritage and treasures of our past, they are integral to our futures. Without significant help, we will lose these ‘houses of good’ and we will all be poorer as a result.

Recent Developments

The House of Good used a standard unit of measure called a ‘WELLBY’ to put a price on the nonmarket value of the activities taking place in church buildings. This is a new tool and its name is derived from the Wellbeing Guidance for Appraisal.

In 2020, our report used a very conservative rate to reach a total of £12.4 billion a year for the social value of church buildings in the UK.

In July 2021, HM Treasury adopted the WELLBY as its primary measure for wellbeing in its guidance (see Wellbeing Guidance for Appraisal: Supplementary Green Book Guidance). But it recommended that the unit be given an average monetary value of £13,000. This official value is more than five times higher than the average figure used in The House of Good.

In short, by using HM Treasury’s figures, in late 2021 we find that the yearly social value of churches in the UK and the activities that take place in them is about £55.7 billion. That is twice as much as local authorities spend on adult social care. For every £1 invested in a church, the return is over £16.