Intangible Heritage

Charlotte Dodgeon

|

||

| A church building can acquire an extra layer of significance through change of use or congregation. The Cathedral of St Alphonsa in Preston was originally a Jesuit foundation dedicated to Ignatius, and is now the seat of the Syro-Malabar Catholic Eparchy of Great Britain. (Photo: Alex Ramsay) |

Over the last decade or so it has become more common for decision-makers to require a statement of significance to support applications either for a grant, or to make changes to places of worship. Not every denomination requires it (the Church of Scotland, for instance), and practice varies across the UK, but the usefulness of a good statement of significance is increasingly clear. Often it is only by setting out what is distinctive and important in a place of worship that the full impact of the proposals can be properly assessed.

Although the main priority is to understand the value of a building’s fabric in architectural, artistic or archaeological terms, a building’s significance can also lie in its intangible heritage; the events that took place, the people with whom it is associated, and the story of its development. To fully understand a building’s value to the community, all of these aspects need to be considered, particularly if it is a place of worship.

This article aims to briefly set out what elements in assessing significance may be evidenced through intangible heritage; how intangible heritage may be defined, with some broad examples from Europe and the UK; and finally, more specific examples relating to intangible heritage within churches and other places of worship.

The Historic England document Conservation Principles: Policies and Guidance (2008) prioritises the need to understand a building’s fabric and how and why it has changed over time, but it also asks those assessing a building to consider:

• who values the place, and why

• how those values relate to the building’s fabric

• the relative importance of each value

• whether associated objects contribute to these values

• the contribution made by the setting and context of the place

• how the place compares with others sharing similar values.

This guidance recognises that ‘people may value a place for many reasons beyond utility or personal association: for its distinctive architecture or landscape, the story it can tell about its past, its connection with notable people or events... for its role as a focus of a community. These are examples of cultural and natural heritage values in the historic environment that people want to enjoy and sustain for the benefit of present and future generations, at every level from the “familiar and cherished local scene” to the nationally or internationally significant place.’

|

||

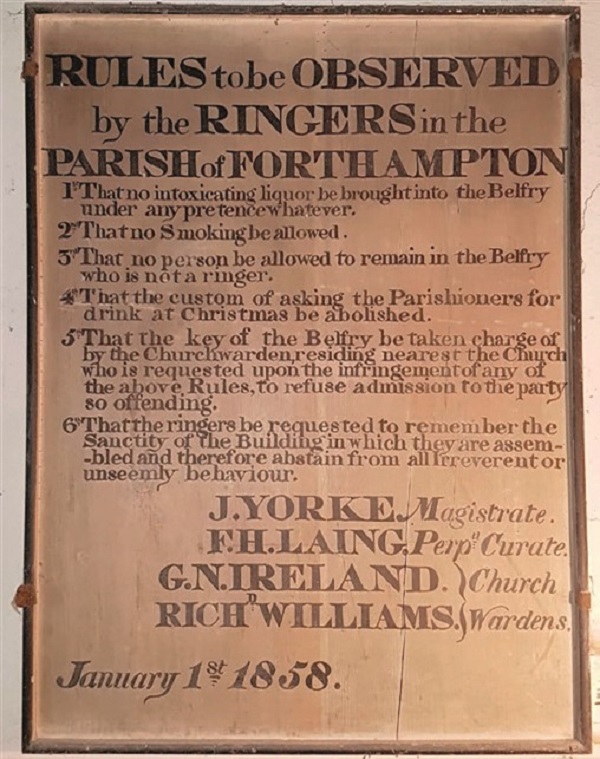

| Found in a Forthampton church, this plaque illustrates the laws governing the conduct of bell-ringers from a bygone age and is an excellent example of the intangible heritage associated with a building and its history. (Photo: Phillipa Holloway) |

If understanding the fabric of the building forms the bones of a statement of significance, understanding these wider elements can help to put flesh on the bones. These elements can often be encapsulated under the heading of ‘cultural heritage’, and ‘intangible heritage’. They have become increasingly interesting to visitors to historic buildings, who often want to know why a place was built, who built it and for what purposes, as well as who used it and how they used it. It is more than understanding the development of the building’s bricks and mortar, it is a people-focused way of looking at heritage. As Robert Palmer put it in his preface to Heritage and Beyond (Council of Europe, 2009); ‘We must continually recognise that objects and places are not, in themselves, what is important about cultural heritage. They are important because of the meanings and uses that people attach to them, and the values they represent. Such meanings, uses and values must be understood as part of the wider context of the cultural ecologies of our communities.’

So what is ‘intangible heritage’? In its simplest terms it’s not physical or material heritage so literally, you can’t touch it. It’s usually about the ordinary, the everyday and the familiar, rather than necessarily something grand or spectacular. It’s something identified and defined by communities, and done by, or transmitted by them, practised, shared and passed on across generations. The UNESCO (2003) definition puts it like this:

Cultural heritage does not end at monuments and collections of objects. It also includes traditions or living expressions inherited from our ancestors and passed on to our descendants, such as oral traditions, performing arts, social practices, rituals, festive events, knowledge and practices concerning nature and the universe or the knowledge and skills to produce traditional crafts… The importance of intangible cultural heritage is not the cultural manifestation itself but rather the wealth of knowledge and skills that is transmitted through it from one generation to the next.

As the UK has not ratified the UNESCO Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage, there is no definitive UK list of intangible cultural heritage, but some sense of the scope of the term can be gained from Germany. In Bavaria for example, in a tradition dating back to 1634, the town of Oberammergau has come together every ten years to perform a re-enactment of the last five days in the life of Christ, the Oberammergau Passion Play, which is now listed as an example of intangible cultural heritage. Another example, also from Bavaria, is a range of traditional techniques used by church painters for the decoration of wall surfaces in imitation of precious materials, which have probably existed for around 600 years.

|

||

| The Arts & Crafts interior of St Cuthbert’s Church in Philbeach Gardens shows the decoration and craft works which were undertaken by craft guilds formed by parishioners in the late 19th and early 20th century. Such an understanding of a building’s social history helps to form an appreciation of its significance. (Photo: St Cuthbert’s archive) |

If we were to look at the UK, then one could see that many customs and festivals would meet the criteria for such a list; from the Padstow ’Obby ’Oss parade on May Day, well-dressing in Derbyshire, the Riding of the Bounds in Berwick-uponTweed, to the Kirkwall Ba’ and plenty of Morris dancing in between; these are local events, with participants passing on the traditions from generation to generation. In terms of traditional crafts and skills, then geographically specific skills include Maund making in Devon, or Kishie basket making in Orkney. Although there are physical outputs, it is the handing down of skills and techniques that form the intangible element.

What might this intangible heritage look like in a church context and how might it be relevant in a statement of significance?

One example of ‘social practices, rituals [or] festive events’ might be the parishes where the ancient ceremony of beating the bounds still takes place. Dating in pre-Norman times, this ceremony usually took place around Rogation week or on Ascension Day. The parish priest, together with the churchwardens and the parochial officials headed a crowd of boys who, armed with boughs of willow or birch, beat the parish boundary markers. On the way, the parish priest prays for the protection of the parish and the whole group sing hymns specific to the occasion. In some places, such as Bodmin, the event is tied to other local customs. This is the realm of the ‘familiar and cherished local scene’, rather than the nationally or internationally significant place, but such customs are a clear example of where intangible heritage (custom and tradition) increases our understanding of why a place is valued by its community.

A more ubiquitous example is bellringing. The practice of ringing a set of church bells sequentially, known as change ringing, originated in the early 17th century following the invention of English full-circle tower bell ringing. The skills required for this, and particularly for the Devon method of call change ringing, are excellent examples of intangible heritage, as is the sound of the bells itself. Boards commemorating the ringing of particular peals, or of laws governing the conduct of bell-ringers, are a further piece in the puzzle, linking to past events.

|

||

| The Guild of St Peter which decorated the interior of St Cuthbert’s Church was led largely by female parishioners, an interesting piece of knowledge that helps us to interpret the church’s tangible heritage. (Photo: St Cuthbert’s archive) |

The value of the intangible heritage associated with bell ringing should be seen as being entirely separate from the values attached to the physical fabric of the bells, which may be significant on account of their age, size or form, or as examples of the work of a particular foundry or founder, or for other historical reasons. Part of the significance of the bells of Christ Church Cathedral, Oxford, for example, lies in the fact that they were moved from Osney Abbey when the see was transferred to Oxford.

Clearly, a church building and its components may have associations with notable people or events; however, where the people or events are more on the local scale, rather than the national, understanding their story can be instrumental in understanding the significance of that building. For example, a Methodist chapel may contain relatively little in terms of features, either architecturally or in terms of fixtures and fittings. However, the events that led up to the founding of the chapel; the people who made donations towards its building, the story of the congregation, and the stories of current members of the congregation can, gathered together, provide a clear picture of a place’s significance beyond the fabric.

Sometimes, the tangible and intangible heritage may be blended. For example, St Cuthbert’s, Philbeach Gardens, is a superb example of an Arts and Crafts movement church. However, unlike Arts and Crafts churches such as Holy Trinity, Sloane Square, which employed the leading craftsmen of the day to carry out the interior decoration, much of the interior decoration at St Cuthbert’s was undertaken by craft guilds formed by parishioners in which women played a leading role, including carving in stone and wood, mosaic work and embroidery. This is well documented in an archive of over 200 photographs of the church and the hall, which includes pictures of the guildsmen and women. So the significance of the tangible heritage is greatly enhanced by our knowledge of the intangible elements – the social history, the ‘who’ and the ‘why’.

|

||

| The history, practices and traditions of the Syro-Malabar congregation which has worshipped at the Cathedral of Alphonsa since 2016 now form an important part of its story. (Photo: Alex Ramsay) |

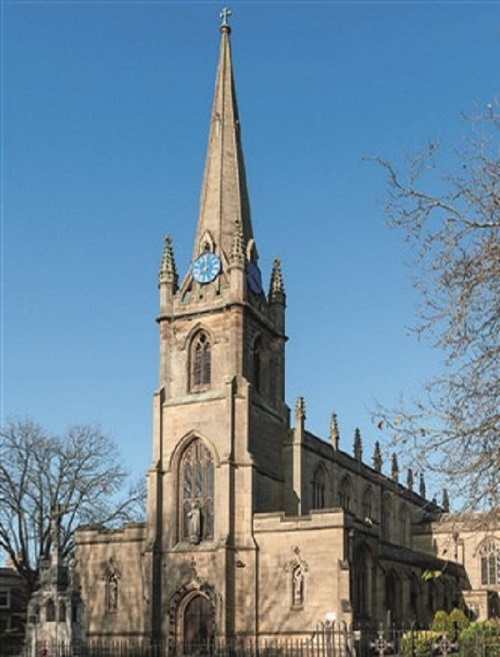

In the case of some churches, an already significant building may develop an extra level of significance through a change in use, or congregation. The Cathedral of St Alphonsa, Preston, is an interesting example of this as it was originally a Jesuit foundation dedicated to St Ignatius. Preston was a recusant stronghold from the Reformation onwards (the town’s name is derived from ‘priest town’), and its Catholic population grew as the 19th century progressed. St Ignatius’ was built in 1833, just five years after the Catholic Emancipation Act of 1829, to the design of Joseph John Scoles, with principal additions by Hansom in 1858. It is a good example of early Gothic Revival architecture and it was the first church in Preston with a spire. It contains many fine fixtures and fittings; it is set within a square of modest but pleasing late Georgian houses and the poet Gerard Manley Hopkins was a curate here in the 1880s. The church was closed in 2014 only to reopen two years later when it was rededicated as the Cathedral of St Alphonsa, the seat of the Syro-Malabar Catholic Eparchy of Great Britain, the first such cathedral in Europe.

Clearly, the building is important on multiple counts, demonstrating significance in terms of both tangible heritage (the style of the building, its setting, original fixtures etc) and intangible heritage (the social history of Preston, the particular time when St Ignatius’ was built, the association with Gerard Manley Hopkins, the changing demographic landscape that led to its closure, the memories of previous parishioners etc). Yet the church’s new lease of life as the seat of the SyroMalabar Eparchy has given it a new element of significance, and one that it is equally important to understand.

|

|

| The tangible significance of the Cathedral of St Alphonsa can be seen in its style, setting and original fixtures, but to fully understand its value the intangible heritage must also be considered. (Photo: Alex Ramsay) | A traditional Syro-Malabar statue that stands in the Cathedral of St Alphonsa, Preston. (Photo: Alex Ramsay) |

Syro-Malabar Catholics, also called ‘St Thomas Christians’, trace their origins and faith to the missionary efforts of St Thomas the Apostle in India in the 1st century AD. They follow the EastSyrian liturgy which dates back to the 3rd century. The Syro-Malabar church follows its own liturgical year and has its own saints and major feasts. It is in full communion with Rome, but retains full autonomy, and it is the second largest Eastern Catholic church (the Ukrainian Catholic Church being the largest). There are some 38,000 SyroMalabar Catholics in Britain, mainly working in the fields of health and IT.

Although there is tangible heritage relating to the Syro-Malabar tradition at St Alphonsa, such as some statues of saints that are not generally known in the Western church, much of the heritage lies in the realms of the intangible – the history of the Syro-Malabar church, and the rites, customs, practices and traditions that now take place in the building. The presence of Syro-Malabar communities across the country can add a further dimension of significance to other churches, and their presence tells part of the story of the life of that church.

In conclusion, the churches and chapels across the UK may be extraordinarily ornate or very simple; they may have celebrated national triumphs or purely local tragedies. However, all of them are a repository not just of building techniques, materials and crafts, but also of the stories of the people who designed them, built them, lived around them and worshipped in them. Understanding and appreciating the intangible heritage of these buildings helps us to develop a better understanding of their significance.