Lighting in the Townscape

Graham Phoenix

|

|

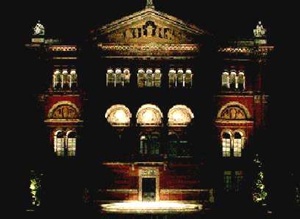

| The Pirelli Garden, Victoria and Albert Museum, London |

When it comes to exterior lighting, the first question that people still quite justifiably ask us is why light at all? With the exception of street lighting, is not most exterior lighting a decorative indulgence, consuming valuable energy resources and offering the constant danger of glare and 'light pollution'? The answer is firstly that it is only badly-designed lighting that puts light where it is not wanted and wastes energy unnecessarily. Better designed lighting is the solution, rather than no lighting at all. Secondly, imagine how drab, depressing and visually uncomfortable our towns and cities would be, if they were only lit by functional, statutory road lamps. Conventional municipal road lighting is designed primarily for vehicle visibility and is most inimical to the rest of the environment. In many cases, pavements and building facades remain unlit or poorly illuminated; and in Britain, predominantly high pressure sodium road-lamps (and even worse the older low pressure sodium type) bathe everything around them in an undifferentiated orange pallor, with heavy downward shadows and little or no colour discrimination.

By contrast, good exterior and area lighting can play a hugely positive role in the way people feel about their environment: it can reveal and enhance our buildings aesthetically, improve our sense of local identity, safety and civic pride; and make people more willing to use the streets, squares and parks after dark, thus boosting an area's night-time use and commercial viability. For all these reasons it is generally accepted that effective, varied lighting of buildings and townscapes, both public and private, is a sound investment that well justifies the relatively small capital and energy costs involved.

Of course, for better or worse, many individual buildings, both historic and modern, are already illuminated. But most schemes are still high on light quantity and low on designed quality. Ninety per cent of exterior schemes are created and executed by non-lighting design specialists. The result is most often the dreaded orange splodge effect, with widely spaced, wide-angle, high-pressure sodium floods located along the facade at ground level, giving an intense, undifferentiated orange wash to the whole building, flattening out the structural details and probably dazzling half the neighbourhood. Cheap it may be, cheerful it is not. Even where luminaires are mounted on the building as uplighters, they are invariably too powerful, so you get blinding 'hot spots', or a light pattern which is unrelated to the architectural form of the building. Public houses around the country are major offenders.

By contrast, using the most modern sources, luminaires and control-systems, specialist practices like LDP and others have developed several sound tenets of contemporary lighting design in recent years, based around tight control, precise application, colour contrast and respect for the architecture. The aim is to use lighting to enable the character of a building or townscape to be 'read' after dark, not obliterated by it.

Today, a new generation of smaller, lower wattage light sources and more precise optics, mean that energy-efficient illumination can now be applied in more discrete 'brush-strokes'. Hopefully too, that awful word 'floodlighting', which has done so much to damage the cause of lighting design through its 'loads-o'-light' connotations, can be banished from the language.

For a lighting scheme to be successful, we need to understand the way in which the architecture - including buildings and townscape features - affect the character of the external space which we occupy. A well designed scheme can be fun, drawing attention to key elements and developing a new character to the space, or it can be modest, in sympathy with the existing architecture. In both cases shadows and darkness are as important as light.

The character of a building may be considered to be the product of its form and the modelling of its form into vertical and horizontal elements; the composition of its primary features, such as doors, windows and the roof-line; and the detailing of decorative components such as cornices, pediments as well as the primary features. By day these elements are emphasised by shadow, surface texture and colour; but by night they may be lost in darkness or in the general flatness caused by a blanket of light.

One approach is to light only the most interesting features of a facade: after all, why draw attention to the boring bits? Cornices, windows, doorways, columns and so on can be picked out with small, narrow-beam, close-set luminaires, leaving the rest in relative darkness. As well as enhancing the architectural form, this largely avoids glare to users and visitors. The lighting of the Pirelli Garden facade of the Victoria and Albert Museum demonstrates this well: the upper window niches are lit from within by low voltage tungsten halogen; while the prominent barrel vaults are picked out with hidden fluorescent strips; and the columns are gently uplit by tungsten spots on clamps, so as not to damage the brickwork. In addition, the three roof-top statues, the pediment and the window reveals are highlighted by narrow-beam spotlights located on the other side of the courtyard.

Another innovation of recent years is the use of contrasting, differing colour temperature beams, made possible by the increased reliability and range of wattage of modern sodium and HID metal halide lamps. The broader colour temperature 'palette' available today allows different building materials, such as granite, steel or sandstone for example, to be given the most appropriate treatment. Rather than negating the fabric's intrinsic colour and textural properties, lighting can actually enhance them.

The need for an uncluttered daytime appearance has also led to the development of far less obtrusive equipment, such as recessed, 'direct burial' spotlights which can be hidden below ground. The size, siting and colour of all fixtures need to be considered carefully, including the wiring, particularly where historic buildings and townscapes are concerned.

The lighting of individual features and buildings cannot be considered in isolation from their surroundings: even the most sensitively lit schemes can be drowned out by crass lighting next door. The award-winning lighting scheme for the Palace Theatre in Cambridge Circus, for example, is now marred by the gross over-lighting of a public house just to the north. All exterior lighting takes place in a context. Certainly the spaces between buildings need consideration too, if illuminated townscape elements are not to appear as a collection of miscellaneous bright spots. Increasingly amenity and pedestrian lighting of various kinds is used to link together the night-time environment and give it an overall coherence.

Just as the character of a facade is the product of its form, features and details, so too is the character of the townscape as a whole. Areas and features need to be brightly illuminated and others need to have a lower level of illumination, in order to create a sense of the modelling and form which gives the place its character by day. Key features which form a cohesive focal point to the landscape by day may become invisible at night, and the sense of structure may be lost.

To combat the growing problem of 'light wars' between commercial properties, to instil an overall civic 'look' to the urban night-scape and to reduce 'light pollution' in general, several local authorities have recently commissioned city-wide lighting plans. Their aim is to integrate all forms of urban lighting in a co-ordinated way. Plans are generally based on assessments of different areas' commercial and historic significance and the form and character of its architecture among other criteria. Advisory recommendations are then laid down for preferred lamp type and luminous intensity in particular zones.

Several local authorities have introduced plans already, including the influential Edinburgh 'Lighting Vision' (now partially implemented) and other examples include Leeds, St Andrews and Londonderry. The proposal to develop a plan for Stratford in East London demonstrates that such co-ordinated lighting treatments do not have to be confined to high-profile urban centres or historic tourist locations. In this 'City Challenge' site, comprising both a conservation area and new build development, a co-ordinated lighting treatment (including street and amenity lighting) is used to link the disparate building elements within the town centre into a cohesive whole. Interestingly, the main lit elements to have been carried out to date affect an unglamorous office-block and a multi-storey car-park.

Outside Britain one of the most impressive European urban lighting strategies to date was developed by the city of Lyon in France, where over the last five years there has been an explosion of creative lighting applications, encouraged and co-ordinated by the local authority. The key to its success was a broad 'loose fit' plan, subsidies for capital investment in new equipment, and the genuine involvement of local businesses and communities in the evolution of lighting schemes for particular locales or sites of interest. Several innovative lighting techniques were developed: for example, 'blue' mercury road lighting for through routes and orange-tinted sodium for secondary roads, give a real sense of hierarchy and order to the night-scape.

In a similar fashion, the Edinburgh scheme incorporated an appropriately 'warm' lighting treatment for the old town along the Castle ridge; while the geometric streets and squares of the Georgian 'new town' area were given a 'cooler', more rational lighting ambience. Even more recently, in a scheme for Trafalgar Square which was 'switched on' last November, contrasting lighting treatments were used to differentiate pedestrian areas, roadways and architectural elements. At the same time the building facades on three sides of the square were given an integrated night-time appearance they have never had before.

However in the absence of city-wide consensus - and in the face of intransigent building-owners happy to blast their buildings with ill-designed lighting schemes - any plan needs regulatory teeth. Some form of planning control on lighting, backed up by ongoing advice and education, must come soon. Ideally each town or city would have a specialist lighting manager, whose job it would be to oversee the introduction of a co-ordinated approach, and to work with architects, designers, road lighting engineers and building owners, to improve the quality of schemes. Lighting design is no longer a private issue; it's a matter of civic and environmental importance to all of us.