Lighting in the Victorian Home

Jonathan Taylor

|

||

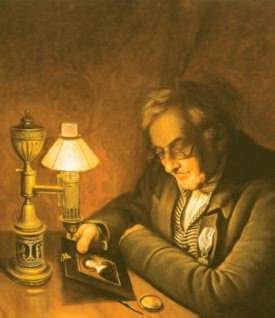

| An Argand oil lamp illustrated in the 1822 portrait of James Peale by his brother Charles Wilson Peale. In this design the reservoir for the thick colza oil supplies one light only and is urn-shaped. The shade is probably silk (Detroit Institute of Arts, USA/Bridgeman Art Library: Founders Society purchase and Dexter M Ferry Jr fund) |

During the 63 years of Queen Victoria's reign,

from 1837 to 1901, life in ordinary houses was transformed by a succession

of technological developments which we now take for granted: flushing toilets,

plumbed-in baths and showers, regular postal deliveries and light fittings

capable of illuminating whole rooms at a time.

At the start of the Victorian period most houses were lit by candles and

oil lamps. Interior fittings included chandeliers (suspended from the ceiling)

and sconces (fixed to the wall). However these were mainly used on special

occasions, and most ordinary events after sunset took place using portable

light sources such as candlesticks, candelabra (bracketed candlesticks)

and oil lamps, and by the light of the fire. By the end of the period gas

lighting was common in urban homes and electricity was being introduced

in many.

CANDLES

Three types of candle were commonly used at the start of the period; tallow,

spermaceti and beeswax. Tallow candles made from animal fat in moulds were

the cheapest but they burnt with a smoky flame which produced progressively

less and less light - and they stank. Spermaceti wax, made from whale oil,

was harder than either beeswax or tallow and was least likely to soften

in hot weather. Improvements in the design of the wicks shortly before the

Victorian period commenced had eliminated guttering, and the plaited wicks

introduced in the 1820s curled out of the flame as they burnt, eliminating

the need for constant trimming which plagued earlier candles. By the end

of the century the modern paraffin wax candle was the most commonly used,

being cheap, odourless and reliable.

Chandeliers, sconces and candelabra varied from their Georgian predecessors

in style only, although shades became popular in the taste for sumptuous

decoration and richness in the late 19th century. The most significant technological

improvements affected various lamps fitted with candles, reflectors and

lenses, often with sophisticated spring-loaded mechanisms for ensuring that

the flame remained at the same height relative to the lens or shade, forcing

the candle to rise as it burnt.

Candlelight was used for most ordinary activities throughout the Victorian

period, from dining and playing cards to cooking, particularly in areas

where there was no gas, until finally eclipsed by electric light. Photographs

of interiors taken by the architectural photographer H Bedford Lemere between

1890 and 1910 (reproduced in The Opulent Eye - see Recommended Reading)

show that in the 1890s fashionable hotels and homes were still being lit

by candlelight and oil lamps. In the drawing rooms and dining rooms of the

wealthy, candelabra were often positioned on the mantlepiece in front of

a pier glass mirror, sconces were also common and on the tables there were

oil lamps, candlesticks and candelabra, often in addition to gasoliers above.

In most cases the candles had shades, some with frills and tassels, others

plain, perhaps made of paper. In the photographs taken in the early 20th

century, many of the candle fittings seen were empty. The frills and tassels

had gone, and the interiors were cool and uncluttered by comparison. Many

of the electric light fittings shown were converted chandeliers and sconces

with light bulbs protruding from imitation candles, illustrating a nostalgia

for the candle which remains as strong today.

OIL LAMPS

Oil had been burnt in lamps at least since the Palaeolithic age, and the

cheapest light fittings used in Victorian homes had changed little since

then, with a simple wick protruding from a small container of whale oil

or vegetable oil. However, much brighter and more sophisticated lamps had

emerged late in the 18th century, the most important being the Argand oil

lamp. This lamp had a broad flat wick held between two metal cylinders to

form a circular wick, with air drawn through it and around it. This in itself

was a revolutionary idea, but its inventor, Aimé Argand also discovered

that by placing a tube or 'chimney' over the flame, the hot gases from the

flame rose rapidly creating a draught and drawing air in from below. Fanned

by a draught from both inside and outside the circular wick, the poor spluttering

flame of early lamps was transformed into a bright, efficient light source

(see illustration).

The one disadvantage for the Argand oil lamp and its many imitators in the

early Victorian period was that the best oil then available, colza, was

so thick and viscous that it had to be fed to the wick either by gravity

from a reservoir above, or pumped up from below. Most colza oil lamps have

a reservoir often shaped like a classical urn to one side which in some

fittings obstructed the light. The Sinumbra lamp got around the problem

by having a circular reservoir around the base of the glass light shade.

|

Left: a type of paraffin lamp with a Duplex burner which was common in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The simple pulley arrangement enabled the lamp to be pulled down low over a table to provide a bright pool of light, or raised to illuminate the whole room. |

The amount of light which can be produced by a wick is limited by the surface area of the wick and the amount of fuel and air able to reach it. As fuel burns at the tip of the wick only. The gas mantle, on the other hand, provides a much larger three-dimensional surface, and is far more effective as a result. Invented by Carl Aur von Wesbach in 1885, the incandescent mantle was the last major breakthrough in oil and gas lighting of the period, before both succumbed to electric lighting. The mantle consists of a skirt of silk or cotton impregnated with a non-inflammable mixture (thorium and cerium), suspended over a fierce flame. When first ignited, the cotton burns away leaving fine, brittle filaments of non-combustible material in its place which glow white hot or 'incandescent'. The mantle works best with either gas or a fine mist of paraffin produced by a pressurised reservoir which is still widely used in camping lamps today, producing a bright, warm light to rival an electric bulb.

GAS

Gas lighting of buildings and streets began early in the 19th century, with most streets in London lit by gas as early as 1816. But for the first 50 years it was generally distrusted and few homes were lit. After gas fittings were introduced in the new Houses of Parliament in 1859 the tide turned. Fasionable town houses constructed in the 1860s often had a central pendant gas light (that is to say a gas light attached to the ceiling) in each of the principal rooms with a ventilation grille above, cunningly disguised in the deep recesses of the ceiling rose. Gas 'wall brackets' were used in place of the sconce, and some staircases were lit by newel lights attached to the newel post. The largest pendant fittings had several burners and were known as gasoliers.

|

|

| Late 19th century paraffin lamp and gas wall brackets in the entrance hall of the Linley Sambourne House, London. (Victorian Society, Linley Sambourne House, London/Bridgeman Art Library) |

Before the advent of the incandescent mantle,

gas lighting relied on a simple open flame. By the mid 19th century the

most common burners produced fan-shaped flames like the Batswing and Fish

Tail burners. The Argand burner, which was successfully adapted for gas,

was the principal exception with its circular flame.

All these gas light fittings and the early incandescent mantles had to point

upwards directing the light towards the ceiling and away from where the

light was needed most, and it was not until 1897 that the gas mantle was

adapted to burn downwards - a useful event to remember when dating gas fittings.

Simple gas lights incorporated a plain

brass, copper or iron gas supply tube with a tap for switching the gas on

and off, terminating in a burner shielded from direct view by a shade or

globe to diffuse the light. Some burners such as the Argand also incorporated

a glass tube or chimney, and around which could be placed a larger shade

of glass or silk. Pendant lights could consist of little more than a vertical

rod turned at right angles at the end to support the up-turned burner, but

they were rarely that simple in the Victorian period. Every element of the

gas light offered an opportunity for embellishment. Early pendant fittings

often incorporated two or more arms forming a loop, gracefully curving down

around the glass lamp shade, with the lamp cradled below. In another design

scrolling arms radiated from a central baluster, a design echoed by the

scrolling arms of the wall brackets.

The shades provided another opportunity for embellishment. Most glass shades

were translucent, either frosted or coloured and were often extremely ornate,

with cut glass decoration or etched patterns. The most elaborate shapes

appeared at the end of the 19th century when designs reached their most

opulent in the Louis XV revival. As well as ornate silk shades on lamps

with chimneys, a variety of other more delicate devices were introduced

at different times, such as shades of glass beads.

By 1890 main stream taste had begun to change dramatically. Although William

Morris, the father of the Arts and Crafts Movement, had established Morris

and Co almost 40 years earlier, it was the second generation of craftsmen

who started to manufacture products on a larger scale, often adopting the

industrial processes reviled by Morris. One of the greatest and most prolific

designers of the new style was W A S Benson who, with the encouragement

of William Morris, had set up his own workshop making light fittings and

other metalwork. His fittings, like those of many of his contemporaries,

were mass-produced, selling through Liberty's in London in particular.

The Arts and Crafts style swept out the clutter from the Victorian interior,

leaving them lighter and brighter in every sense. Richly decorated surfaces

were replaced by plain ones relying on the warmth of natural materials and

simple craftsmanship for their interest. Those elements like the fireplaces

and light fittings which remained as richly ornamented as ever before took

on a new importance, focussing attention. Often the decoration of fittings

can be described as 'Art Nouveau' for their graceful, flowing lines and

lack of any clear historical influence, but revivalism remained common,

and most homes at the turn of the 19th century borrowed heavily from the

Tudor and Elizabethan periods in particular.

ELECTRIC LIGHTING

The rise of the Arts and Crafts movement coincided with the emergence of

electric lighting, and although many new homes continued to be built with

gas lighting until the First World War, Benson's work and that of other

leading Arts and Crafts designers is often associated with electric light

fittings.

In 1879 Thomas Edison beat rivals like Sir Joseph Swan to perfect the first

viable incandescent light bulb. One year later, Cragside, a rambling mansion

near Newcastle designed by Norman Shaw, was the first house to be lit electrically,

using Swan's 'electric lamps'.

The light bulb had enormous novelty value and the earliest fittings displayed

the bulb quite prominently. Early light bulbs were available in a wide variety

of shapes and patterns, often highly ornamented, but as the novelty value

wore off and the short life span of the bulb was recognised, attention turned

back to the shade and the fittings themselves.

By Queen Victoria's death in January 1901, electric lighting was still in its infancy.

Gas lighting was common in the cities and larger towns, supplemented by

candles and oil lamps, but in smaller towns and villages and in the countryside

lighting remained almost exclusively by candles and oil lamps. All the principal

forms of lighting were thus in use at the same time, and it was not until

after the First World War that electric lighting finally emerged as the

predominant source of light in the home.

Recommended Reading

- Nicholas Cooper, (with photos by H Bedford Lemere) The Opulent Eye, The Architectural Press Ltd, London, 1976

- Temple Newsom Country House Studies No4, Country House Lighting 1660-1890, Leeds City Art Galleries, 1992

- Cecil Meadows, Discovering Oil Lamps, Shire Publications, Princes

Risborough, 1972

- Josie Marsden, Lamps and Lighting, Popular Collectables, Guinness

Publishing, Middlesex, 1990

Above: a paraffin

oil lamp suspended from the centre of the morning room, Linley Sambourne

House, London. (Linley Sambourne House, London/Bridgeman Art Library)

Above: a paraffin

oil lamp suspended from the centre of the morning room, Linley Sambourne

House, London. (Linley Sambourne House, London/Bridgeman Art Library)