Lime: The Basics

Jonathan Taylor

WHAT

IS IT?

At times the term 'lime' is used rather confusingly to refer to a variety

of products made from limestone and chalk (both forms of calcium carbonate).

In the context of building conservation, the term is most commonly applied

to types of binder used in plaster, limewash, render and mortar that are

made by burning limestone or chalk to make quicklime and then slaking

this with water.

Mick Barnfields of St Blaise carrying out mortar repairs |

Mortar is the stuff between the bricks or blocks of stone in masonry walls

which closes the gaps and makes the structure wind-proof. It is usually

composed of washed sand and other aggregates, with a binder to protect it

from erosion by the wind and rain. In some areas of the country, coatings

of the same material as the mortar are commonly applied over the stone or

brick to form a coarse, exterior plaster known as render or, in Scotland,

harling. This is often finished with limewash (lime mixed with tallow or

linseed oil), coloured with natural earth pigments which produce delightfully

soft, uneven colours.

Prior to the introduction of cement in the early 19th century, the binder

used in mortar and render was almost invariably lime, and this material

continued to be used widely until the end of the century.

NON-HYDRAULIC

LIME

Lime is made by first burning chalk or limestone to form quick lime (calcium

oxide) and then slaking the quicklime with water (forming calcium hydroxide).

If no clay is present in the original limestone or chalk, the resulting

lime is said to be 'non-hydraulic'. This form stiffens and eventually hardens

by reacting with carbon dioxide which is present in rainwater (in the form

of a weak solution of carbonic acid) to form calcium carbonate once again;

a process known as carbonation.

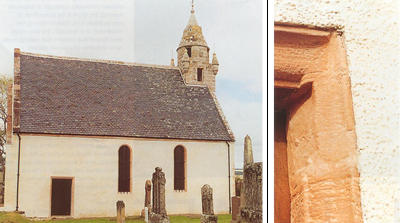

Wardlaw Mausoleum: Interior conservation work included lime plastering and limewashing |

LIME PUTTY

For conservation work, non-hydraulic lime is usually used in the saturated

form known as 'lime putty'. This is supplied to site covered by a thin film

of water in air tight tubs, to minimize the risk of carbonation. It is made

by slaking the lime with a slight excess of water. When matured (lime putty

continues to mature for months), the result is the purest form of non-hydraulic

lime, ideal for making fine plasterwork and limewash, but also widely used

for pointing masonry and making render, daub and other lime-based mortars.

DRY-SLAKED LIME

To construct towns and cities at the rate required in the late 18th century,

Gerard Lynch, the historic brickwork consultant, has convincingly argued

that most lime must have been made on site and used immediately, without

waiting for it to mature. Dry-slaking is ideal for this: lumps of fresh

quicklime are slaked with a limited amount of water and then immediately

covered over with damp sand; then, after screening to remove any remaining

particles of unslaked quicklime, the mixture of sand and lime is knocked

up with water ready for immediate use, although it was probably 'banked'

to allow the lime to mature for a few days first.

Wardlaw Mausoleum: The external lime harling (or render) was repaired successfully by William Napier and The Scottish Lime Centre using a complex, or hybrid, mortar to match the original, and then limewashed |

BAG LIME

Most builders merchants supply a dry form of non-hydraulic lime which can

be used like lime putty if allowed to soak in water for a while. Known as

'dry-hydrated' lime or 'bag lime', it is generally considered to be inferior

to lime putty, not least because an unknown proportion will have reacted

with carbon dioxide by the time it reaches the site.

HYDRAULIC

LIME

If the limestone contains particles of clay, after burning at 950-1200°C

and slaking, the lime produced sets by reaction with water. Limestone containing

the lowest proportion of clay (less than 12 per cent) results in a feebly

hydraulic lime with properties close to non-hydraulic lime, which is relatively

weak, permeable and porous. Higher proportions result in successively stronger

and less permeable lime mortars. Because they react with water, hydraulic

limes are usually supplied to site as dry powder. However, they can also

be made by dry-slaking on site and may be knocked up with water and banked

on site for a few days.

Banking is not thought to harm the mortar despite the commencement of the

set, as the bonds formed during banking are reformed later, after the mortar

has been knocked up again. Indeed, the process may actually result in a

better set ultimately, as the lime is more mature.

POZZOLANIC ADDITIVES

The hydraulic set takes place due to complex chemical changes involving

the hydration of calcium silicates and aluminates in particular. A similar

effect can be achieved by adding pozzolanic additives to non-hydraulic lime

as these additives contain highly reactive silica and alumina. Pozzolanic

additives include some types of brick dust, fired china clay (such as metakaolin

and HTI/'high temperature insulation'), PFA/'pulverised fuel ash', volcanic

ash and pumice.

HYBRID MORTARS

Mixtures of hydraulic and non-hydraulic lime were used in the past to create

what English Heritage has termed 'hybrid' lime mortars (Historic Scotland

describes them as 'complex' mortars). However, the performance of a hybrid

mortar was called into question by English Heritage following a number of

spectacular failures, after which it banned the use of these mixtures on

grant-aided work. The results of a study by the Building Research Establishment

and English Heritage, which are now being prepared for publication, show

that the addition of a small amount of non-hydraulic lime (5-10 per cent)

improves workability but anything above this level significantly impairs

durability. Mixes containing 1:3:12 and 1:2:9 hydraulic lime:non-hydraulic

lime:sand actually performed less well than a standard 1:3 non-hydraulic

lime:sand mix in their tests.

AGGREGATES

Generally, mortars for conservation and repair work should include the same

range and types of aggregate particles as the original mortar, as well as

the same binder and any pozzolanic additives, unless any of these are actually

harmful. This is to ensure that the new mortar performs in the same manner

as the old and is similar in appearance. The original mix is best determined

by analysis. Several companies offer mortar analysis services - see The

Building Conservation Directory or the Directory pages of this

website for details. Common aggregates include local river sand and particles

of brick (which may not have any pozzolanic effect), stone and old mortar,

as well as extraneous material from the firing process in particular, such

as specs of coal dust. The choice of aggregate has a significant effect

on the performance and the appearance of lime mortar. In particular, any

aggregate used should be well washed and graded, free from sulphates (this

tends to rule out the addition of coal dust even if found in the original

mortar), clinker and alkalis such as sodium and potassium hydroxide. Other

factors which have a significant effect on performance include particle

size and shape. The correct specification of the mortar for pointing or

rendering old buildings is vital. Bear in mind that some proprietary mixes

may contain cement, and that a mortar which is too hard or too impervious

may cause extensive damage to historic masonry and other structures.

Further information

- The Scottish Lime Centre. For details of training programmes and other services offered by The Scottish Lime Centre Trust & Charlestown Workshops, please phone 01383 872722, E-mail info@scotlime.org, or visit their website www.scotlime.org

- Hybrid mortars. For details of English Heritage's research into hybrid mortars, please phone English Heritage's Conservation team on 020 7973 3073

.