Metal Windows

Richard Baister

|

||

| Bronze windows in a London theatre. (Photo by Jonathan Taylor) |

Windows are an important part of any building and their architectural style often reflects its age and overall heritage significance. They are often entirely functional in design and perhaps unlike many other building features have been developed in line with the availability of new materials and working techniques. Whereas windows originally performed as a functional blocking of an opening, we now expect them to meet high standards of light transmission, thermal performance and user operability and security, standards for which earlier windows were not originally constructed to achieve.

When looking at the refurbishment of historic windows it is important to recognise these performance limitations together with the perceived difficulties of repair and future maintenance. However, these difficulties should not be seen as justification for their replacement with new items but simply as a requirement to undertake a full assessment and develop appropriate repair and enhancement proposals that carefully balance the requirements of function, aesthetics and heritage. In this way it should be possible to retain these heritage significant items for many years to come.

DESIGN AND CONSTRUCTION

Window design has always followed the availability and manufacture of glass, with the earliest windows incorporating small units of glass (known as quarries) joined together with lead to form a single fixed leaded light that filled the opening. However, to operate as an opening window a hinged frame was required, and with the advent of larger panes of glass, frames of timber or metal became the norm. The metals most commonly used for window frames are outlined below.

Wrought iron is fibrous in nature and contains up to four per cent impurities which are introduced during the manufacturing process. It was first used for metal window production in the 16th century as it provided a stable framework to support leaded lights allowing them to be opened and closed for ventilation. A basic opening light would have been originally formed from flat wrought iron bars, fire welded at the joints by an experienced blacksmith with a leaded light copper wired to the framework. Greater weathering could be provided by soldering flat bars together to form more complex sections, a method which was used until hot rolled sections became more generally available.

|

|

| Wrought iron window to former mill showing jacking corrosion of the frame and opening light sections. (Photo by Richard Baister) | |

|

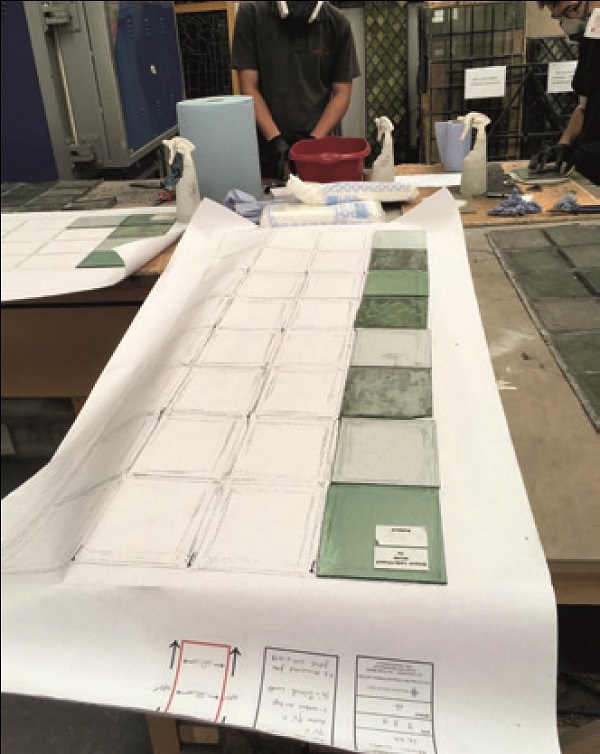

|

| Cast iron pavement lights removed for full assessment in the workshop. (Photo by Richard Baister) |

Steel became available for window production after 1856 when Sir Henry Bessemer developed his new production processes that allowed large quantities of low impurity steel to be manufactured at a much lower cost than the very labour intensive wrought iron production process. The introduction of standard window sections known as the universal suite in 1918–20 by the Steel Window Association then accelerated its use in window manufacturing up until its heyday in the 1960s, where it was extensively used for both domestic and civic projects. Crittall, the largest manufacturer of steel windows in the UK, was responsible for approximately 40 per cent of all domestic production – hence the generic use of their name to describe steel windows from the period. The longevity of steel windows was also improved significantly in 1955 by the mandatory requirement for hot dip galvanising of frames.

Wrought iron and steel are strong in both compression and tension, allowing smaller and lightweight section sizes to be used in window manufacture with typical sections only 6mm thick. As a material it requires painting to provide an acceptable level of corrosion protection.

Typical defects include: corrosion jacking of the wrought iron where paint coatings have failed causing localised distortion of the opening light; shakes and flaws in the metal from its manufacture leading to small areas of delamination; and dissimilar metal corrosion.

Cast iron became a popular material for window manufacture in the 19th century due to the reduced costs of iron production and working techniques developed during the Industrial Revolution. Windows would be cast at the foundry using sand moulds based on a master pattern, allowing cost effective replication of the units. However, cast iron being more brittle resulted in heavier window sections being required over wrought iron units. Cast iron is typically more corrosion resistant than wrought iron, however it also needed to be painted to retain its aesthetic appearance and prevent corrosion.

Typical defects include fractures of the cast iron sections with possible loss of elements such as glazing bar sections, and distortion and porosity of the sections as a result of poor casting techniques or sections cooling at different rates.

Bronze or architectural bronze (brass) was often used as an alternative to wrought iron on more significant buildings where the material could be patinated and expressed as part of the overall building design. The material is very corrosion resistant but its high cost of production resulted in it mainly being used on more prestigious projects. As a material it has good corrosion resistance, however it needed to be patinated and waxed to provide an acceptable aesthetic finish.

Typical defects include surface corrosion of the brass where protective wax coatings have been lost with the formation of green copper sulphate and carbonate deposits. Aluminium windows, although commonplace today, were not commercially available in the UK until the 1930s due to the very high cost to produce the metal from its base ores. Windows were made either by casting, by mechanically joining bar and plate material or, more commonly, by using extruded profiles to form close fitting window sections. Aluminium corrodes readily to form a layer of surface oxides which then act to protect the main body of the material. This can change the appearance of the aluminium, and surface coatings (passivating) are often applied to retain its natural appearance. Typical defects include salt or bimetallic corrosion, and brittleness of sections through work hardening.

Copper and zinc although not commonplace have also been used for window fabrication. These are typically bespoke and need to be carefully considered in determining an appropriate repair specification.

|

||

| Early aluminium windows showing surface corrosion to the metalwork together with physical damage where services have been introduced to the building and degradation of the timber glazing beads. (Photo by Richard Baister) |

Pavement lights became very popular during the 19th century and were typically formed of cast iron or bronze with cast glass blocks. Being situated at ground level, they are exposed to very harsh conditions with a high risk of impact damage to the glass blocks or the grilles themselves. Although original paint coatings may have been applied to the cast iron, they are often not maintained through the life of the pavement light. Typical defects include physical damage due to excessive loading, and damage to glass blocks.

THE ASSESSMENT PROCESS

Essential in any assessment process is understanding the heritage significance of the windows themselves. This may be largely based on the originality of the windows to the building, but may also include other factors such as the construction materials or any unusual features or aesthetics that have been incorporated. Where windows are deemed to be of greater heritage significance, increased efforts should be made to retain and repair them.

For listed buildings the repair or replacement of windows may be seen as a material change, requiring prior approval from the local authority (listed building consent), and specialist advice from an accredited heritage professional should always be sought.

The majority of condition assessments are carried out on site and it is necessary to fully inspect and record the condition of the window. This can be difficult if the windows have been poorly maintained in the past and defects are covered with many layers of paint coatings. Wherever possible the assessment should be carried out in situ as removal can put the window at risk of further damage. However, in some cases it may be necessary to carefully remove sample windows for inspection in the workshop where the true condition and difficulties associated with the refurbishment can be established.

Each window should be examined both internally and externally to identify and record:

- original construction material – either through inspection or sample analysis

- physical size of the window including section profiles and glazing thicknesses

- visible defects on the window including any wear in operation and missing ironmongery

- the fixing method and the condition of fixings

- paint coatings and other finishes, including sampling to identify leadbasedpaint systems where necessary.

A photographic record should be made of the internal and external elevations of the window, with specific defects recorded on dedicated photo sheets.

From the condition assessment a treatment recommendation can be prepared which details the works required to undertake repairs. The extent of the repairs will vary upon the findings and a number of options from minimum intervention through to full replacement can be considered. These may include:

|

||

| Leaded lights being rebuilt by a specialist restoration company (Recclesia). The glass is being cleaned and retained in its original location by using a rubbing of the original panel. (Photo by Richard Baister) |

Stabilisation Where minimal repairs are required it may be possible to undertake treatments that will stabilise the condition of the windows and prevent further degradation without the need for their removal, which

could result in damage to the surrounding masonry. This may include ensuring that paint

coatings are reinstated or that mechanisms

are lubricated and made functional again.

They would then not require more invasive

works at this point in time.

Repairs Minor repairs can be carried out in situ, however more extensive repairs require the removal of the window to a workshop. Removal should be carried out by companies with experience of the particular window system, with all units individually tagged to record their original location. The window may need to be partly deglazed to access fixings or to assist with the disassembly, in which case all removed components should be tagged together.

Temporary windows may be required while the existing are being refurbished and usually these should be weathertight to prevent unnecessary damage to the building interior.

Once in the workshop the windows can be fully dismantled for treatment. Where paint layers are to be removed, sampling should be undertaken to record evidence of earlier treatments and colour schemes, whether for replication later or simply for record purposes. The treatment of the frames to remove paint or corrosion will require a methodology specific to the particular material type and to minimise the risks from lead-based paints. Iron frames may be flame stripped or air abrasive cleaned, whereas bronze and aluminium frames require less aggressive cleaning techniques.

Corroded or missing frame sections will require repair with new sections to match the existing. Some limited sections are commercially available, although most of the missing ones will require bespoke new sections made to match the original details. These are then fixed mechanically or by welding or brazing to the original frame to reinstate full section profiles. Trials will always be required when welding repair techniques are used to ensure that full penetration welds can be made to the original material without stressing or distorting it.

Following repair of the frames the glazing can be reinstated using salvaged glass that was removed prior to the refurbishment, and new glass that matches the original material where possible in terms of movement and colouring. For frames that are putty glazed an appropriate metal glazing putty should be used rather than a traditional linseed oil putty, as unlike timber frames the oils cannot be drawn out of the putty. Metal or timber glazing beads should be refurbished and refitted where in good condition, or new elements manufactured where they are missing or damaged through use.

|

||

| Matching glazing bar sections for repair. Available sections may need to be modified to exactly match original section sizes. (Photo by Richard Baister) |

Where leaded lights have been removed it is likely that they also require refurbishment. Where a full rebuild is required, the original glass quarries should be salvaged and carefully cleaned before reassembling to match the original appearance, and any leading repairs should be made using lead ‘cames’ of the same section as the original.

Missing ironmongery should be replaced to match the original and adjusted to ensure that the completed opening lights can be closed to seal against the frame. This can include the fitting of wedge blocks to support the opening light in its closed position, therefore preventing long-term distortion of the frame.

Protection It is important to choose a suitable protection system that will prevent the metalwork from corroding and tarnishing. Ferrous frames will require full protection after treatment with a suitable paint coating system. These can be based on traditional oil paint (albeit lead-free) or modern, longer life epoxy or alkyd paint systems. The frames can also be zinc flame sprayed to provide additional protection, which is a similar process to galvanising. However, it is less prone to distortion so is more suitable for complex frame sections.

Bronze frames can be chemically repatinated or coated with tinted lacquers to achieve a traditional aged appearance before being coated with waxes and buffed to a high shine. Aluminium frames once treated can be coated in clear lacquers to retain their silver appearance.

Improvements Original windows can be improved to provide greater thermal or acoustic insulation by replacing glass panes with modern glazing systems. Slim double-glazed units can be produced in thicknesses as little as 10mm, providing a significant thermal improvement over single-glazing, and the new Pilkington Spacia glazing system can supply vacuum sealed units which are only 6mm thick while still achieving comparable thermal performance to that of a 27mm double-glazed unit.

However, where new modern glass systems cannot be utilised then secondary glazing systems fitted to match the original window fenestration is often a more viable option and avoids heat-loss through the metal frame itself.

Draught sealing is also a popular improvement. However, again this can be limiting if the frames were not originally designed for seals. The application of selfadhesive draught seals can be effective after frames have been refurbished and gap variances improved.

Security The use of laminate or toughened glass may be required where the windows need to conform to Part N of the building regulations which will also provide enhanced security over a standard glazed unit. Window locks or restrictors can also be fitted as part of the refurbishment. The choice of locks should be carefully considered to be in keeping with the overall window aesthetic and any stays should restrict the window without stressing the units unnecessarily.

|

||

| New cast iron windows manufactured to replace existing units. (Photo by ©Dominic Grosvenor, Barr and Grosvenor). |

Replacement In extreme cases it may be necessary to consider replacement of the window units rather than undertaking repairs. Where this is necessary the replacement should be sympathetic to the original design intent, using similar materials while conforming to modern standards for thermal performance and security. Often the decision to replace windows is taken without a full assessment of the windows themselves which can lead to poor quality imitations and the loss of important heritage features. Replacement should always be the last resort and not taken as the easy option.

A successful refurbishment of traditional windows starts with a detailed condition survey and the development of a suitable repair specification that can be taken on by an experienced contractor with good knowledge of the window system and applicable repair techniques. Repairs can never achieve the performance requirements of modern window systems, however this should never be used as a reason in itself to replace traditional hand crafted and historically significant items.

Acknowledgements:

With many thanks to Peter Meehan for his assistance and advice in identifying suitable photographic images.