Monumental Brasses

William Lack

|

||

| The brass of Margarete de Camoys, c1315, St George’s, Trotton, Sussex (Photo: Derrick Chivers) |

The earliest brasses were laid down in this country in the early 14th century and their popularity as memorials for the landed gentry and wealthy middle classes continued until the mid 17th century. Iconoclasm, greed and carelessness have reduced the original number of brasses to a current total of about 8,000. Many of these are to be found in comparatively isolated churches throughout the country with a concentration in the Home Counties and East Anglia. A brief revival in Victorian times produced many notable designs and occasional examples are still made.

The greatest danger facing brasses is theft. Therefore the first priority of the conservator is to ensure that the brasses are secure, either in their original slabs or in an alternate setting.

Every brass was originally set in a stone slab, often of Purbeck marble, which was itself an integral part of the monument. The brass was secured with brass rivets set in lead plugs let into the stone and the plates were bedded on pitch. Over a prolonged period, pitch deteriorates and loses its adhesion, rivets spring or pull out of the stone, and the endless pressure of feet causes plates to expand laterally and to bow. As a result, plates work proud of their slabs and become loose and vulnerable. Brasses which have been reset in their slabs in the past using screws or other inappropriate techniques are particularly vulnerable. When set in the floor of a church, corrosion is not usually a problem unless the brass has been relaid and bedded unsuitably, for example on cement.

The conservator’s first task is to clean the plates, taking care not to disturb the existing patina. It is most important that this is done without the use of chemicals. After light washing in distilled water or white spirit, dirt, corrosion and calcareous accretions are carefully scraped off and lifted with a scalpel. New brass rivets are fitted and the brass secured in its original slab with the plates bedded on fresh bituminous mastic with the rivets set in an inert resin grout. This process, which follows the original methods, provides support and secure anchoring for the brass and protection from damp.

On church floors slabs have usually survived remarkably well. However, problems which are encountered include fracturing of the stone and deterioration of the surface, either caused by heavy foot traffic or by environmental conditions where rising damp and migrating salts have caused crumbling of the stone surface, often leaving edges of plates exposed.

Wherever possible, a damaged slab should be conserved by a stone conservator, not renewed. It may need to be removed from the floor, dried out and the level of soluble salts reduced by expert treatment. Any fractures will need to be pinned with stainless steel dowels and the surface may need to be consolidated. Limestones and calcareous sandstones may be consolidated using limewater but not an impervious chemical, as most proprietary treatments are liable to lead to further deterioration and cannot be reversed. In extreme cases the surface may need to be dressed and new indents cut.

|

||

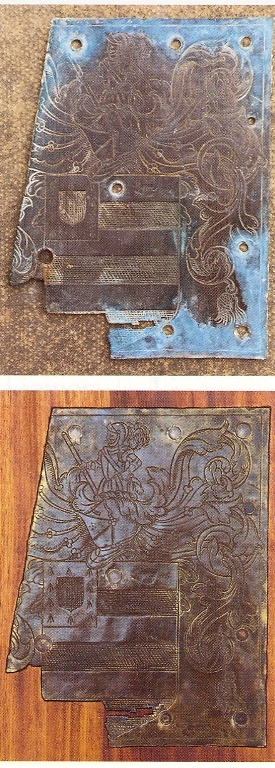

| Above: Two Victorian brasses from St George’s

Chapel, Windsor; one before cleaning and the other

after.

Below: A 17th century example, before and after cleaning. |

||

|

The Victorian fashion for tiling church floors resulted in the loss of many original stone slab floors. Brasses were often removed to the walls where they may now be found nailed or screwed directly to damp, plastered and limewashed walls. Not only are such brasses more vulnerable to theft but they often become corroded. It is common to see green (copper carbonate) corrosion around the edges of the plates and ferrous corrosion around the fixings.

Where corrosion has occurred, the brass must be removed from the source of damp and cleaned. If the original slab cannot be reused, or if replacing it in its original position would entail unacceptable risk of further deterioration, a cost-effective solution is to mount the brass on a board. While this may not be an ideal solution from an aesthetic or historic viewpoint, it nevertheless provides better security and protection against corrosion and wear, provided the brass is properly rebated and riveted to the board. The board should be spaced away from the wall to allow air circulation behind and should be secured with stainless steel anchor bolts. The wood should be stable and free from natural chemicals which may react adversely with the brass. For this reason oak, Douglas fir and certain other hardwoods are not suitable. Iroko, beech and cedar of Lebanon are among those currently in use although each has its disadvantages.

Victorian plates present unique problems. Many of them were secured with rivets soldered to the reverse and these joints can fail, leaving edges proud of the slab. In such cases it is usually necessary to lift and conserve the whole plate. These brasses were often produced with coloured infill in the engraved lines and their surfaces were polished and protected with lacquer. Where the lacquer has broken down, either as a result of polishing or environmental conditions, the brass will need to be cleaned, lightly polished and re-lacquered with a cellulose lacquer such as Incralac.

In the 1960s and 1970s brass rubbing achieved great popularity and many celebrated brasses were rubbed intensively. Brass rubbing was perceived to damage brasses, and a by-product of the brass rubbing boom was the emergence of resin facsimiles. In churches where brass rubbing is most popular, facsimiles can be introduced to ensure the protection of the originals. Although excessive rubbing almost certainly contributed to a loosening of some brasses and caused damage where plates were not securely fixed and could be flexed vertically, recent study (1) has shown that brass rubbing, if properly carried out, does not wear the surface.

Most damage has been caused by the use of metal polish and by injudicious use of coverings such as coconut matting and carpets with underlays which harbour grit. The practice of laying fitted carpets with rubber underlays prevents floors and slabs from breathing and inevitably causes corrosion to brasses, while any grit caught beneath abrades the surface.

Some medieval brasses were made by reusing older ones, and lifting brasses for conservation has revealed many unknown ‘palimpsests’, with the older engravings preserved on the reverse side. After conservation, the reverse will again be concealed so they should be recorded by taking a rubbing or by making a resin facsimile for display elsewhere in the church.

Where brasses have been conserved, the only action necessary to maintain them is to ensure that they are kept regularly swept with a soft brush and protected with regular applications of a micro-crystalline wax.

RECOMMENDATIONS

- Where brasses become loose or proud of their slabs or seriously corroded, advice should be sought from the local DAC, a conservator or a specialist conservation architect. Parts which become detached must be locked away.

- Where possible brasses and slabs should be roped off to prevent people walking on them. If this is impossible they should be covered with carpet with felt underlay. Rubber-backed carpets or abrasive matting should not be used. In churches with resident bats, brasses should usually be covered to protect them from acidic droppings.

- Where excessive foot traffic is damaging brasses and slabs, consideration should be given to removing them to a quieter location or mounting them against a wall.

- Brasses and slabs should be swept regularly with a soft brush. An occasional wipe over with a rag soaked in white spirit will remove dirt and some stains.

- Brasses should never be cleaned with metal polish or proprietary cleaners as they contain abrasives and chemicals, principally ammonia, which damage the surface.

- Brasses and slabs should not have furniture or flower arrangements placed on them.

~~~

Recommended Reading

- Malcolm Norris, Monumental Brasses: The Memorials, Phillips and Page, London, 1977

- Malcolm Norris, Monumental Brasses: The Craft, Faber and Faber, London, 1978

- HK Cameron, 'Technical Aspects of Medieval Monumental Brasses', The Archaeological Journal, CXXXI, 1974

Notes

(1) 'Wear of English Monumental Brasses Caused by Brass Rubbing', by JT Yates, TE Madey and HL Rook, Nature, 243, 1973