Nuts and Bolts

An Introduction to Conservation and Repairs

Jonathan Taylor

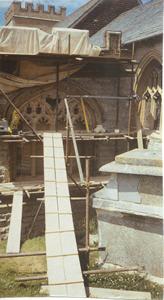

Parapet repairs at St Andrews, Cheddar (St Blaise Ltd) |

It is a common misconception that listed buildings cannot be altered or demolished. They can be. Listing simply means that all such proposals must be approved by a statutory authority before work commences. Indeed, some element of alteration is inevitable as a result of ordinary conservation and repair work, and in some cases even the demolition of some part may be required in order to ensure the survival of the building as a whole. Surprised? Conservation is a very broad concept.

The term 'conservation' encompasses all actions that are required to ensure the survival of the building in the long term, including, where necessary, sympathetic alterations. The term 'preservation', on the other hand, is much more limited in scope, describing only those actions which prevent change or protect a building from change, and therefore excludes all alterations, no matter how essential. The third term frequently used in the same context is 'restoration'. This term describes action taken to reverse more recent alterations and is thus very much a process of change, removing later alterations and often putting back features based on the design of elements removed in the past.

In conservation circles restoration is often frowned on due to the number of poor restoration schemes carried out in the past, often based on the most vague concept of what might have been, and removing any later features, irrespective of their historical interest. Medieval buildings in particular suffered at the hands of Victorian architects who 'restored' features which had never existed in order to create a thoroughly Gothic aesthetic. In the best conservation schemes restoration is limited to the bare minimum, so that the authenticity of the building or object is not compromised. For example, where crumbling stonework has to be replaced, the new stonework might be carved to its original profile where it is clear what this would have been: where the original design is unclear, however, a new design may be preferable to conservationists since work which imitates the original can look fake, casting doubt on the authenticity of original elements and detracting from their historic value. On the other hand, repairs which stand out can also detract from the enjoyment of original architecture, so a balance is required where new work can be distinguished from the old without harming its character.

THE SEVEN DEADLY SINS

Old buildings do not look after themselves, no matter how well constructed. Most materials are liable to deteriorate when they remain damp for long periods: iron fixings rust and can shatter the stone into which they are built; ancient oak beams can be hewn out by deathwatch beetle; and dry rot can crop up far from the nearest source of damp. Nevertheless, old buildings have lasted hundreds of years perfectly well with little more than general maintenance, and arguably the greatest threat to their future comes from ill-considered intervention by their owners.

Broken roof tiles contributing to damp in the wall below |

1.

Poor maintenance

Perhaps the most common causes of dry rot and other forms of timber decay

in old buildings are blocked gutters and the failure of roof coverings (for

example, slipped and broken slates and clay tiles, damaged and stolen lead

and other sheet metal roof coverings). Look out for the tell-tale signs

of damp patches and green algae growth around hoppers and downpipes which

often indicate nothing more complex than leaves or a dead pigeon blocking

the pipe - easily rectified if caught in time. Regular tile slippage can,

however, indicate more fundamental problems as old nails and wooden tile pegs

used to fix the roof coverings often begin to deteriorate all at once.

If ignored, blocked gutters and gaps in the roof covering can cause adjacent

timbers inside the roof to deteriorate, and creating the ideal conditions

for wet rot, dry rot and beetle larvae, often far from the original moisture

source, with little sign of moisture penetration below.

|

| Broken roof tiles contributing to damp in the wall below |

|

| Damaged render |

2. Sealing damp in with modern renders, sealants

and concrete floors

Most old buildings

have solid walls which

keep out the rain due to their mass. Moisture absorbed into the thick

walls is absorbed and retained, but only temporarily. Rough textured surfaces

of natural stone, brick and

lime renders encourage evaporation, and even in the British climate damp

is unlikely to reach the interior in sufficient quantity to become a problem

if the walls are sound and well maintained. Nevertheless, modern paints,

renders and other coatings are often unwisely

applied to overcome a damp problem without properly identifying

its cause, and the results can be disastrous. Impervious surface coatings

lock moisture in and inevitably crack as the structure expands and contracts

with changes in temperature, allowing more moisture in and trapping it.

Covering the floor or relaying it with a damp-proof floor slab membrane

can also prevent natural evaporation, causing moisture to rise through

walls and columns instead. This is often seen as a tide mark of salt crystallisation

and stone decay, one foot or so above floor level.

3. Cement-rich pointing

Although suitable for use in a modern masonry construction, cement rich

mortars can cause substantial damage when used to repoint traditional

masonry. The cement mortars are much harder and allow less movement than

the original lime mortar remaining in the core of the wall. As pointing

usually replaces only the outermost inch or so of mortar, any movement

in the wall will be resisted by the shallow depth of rigid masonry at

the face, causing stress. As a result of this and other factors, such

as salt crystallisation and frost action, pointing with a cement-rich

mortar can often cause masonry to decay.

4. Inappropriate cleaning

Dirt often adheres tightly to surfaces and may extend deep into the pores

of a material. Many of the most effective chemical cleaning methods used

today and all mechanical methods (such as sand blasting, sanding and other

abrasive techniques) are effective because they can remove not only layers

of dirt but also the surface of the material being cleaned, including

metal, glass and stone. The effect of inappropriate cleaning methods can

be seen most clearly in the softening of edges and the loss of more and

more detail with each cleaning. Even the most gentle techniques such as

low pressure water cleaning entail some risk of harm, and proprietary

cleaning products used in the home (for example for cleaning brass) are

no exception. There are almost as many other risks attached to cleaning

as there are cowboy contractors willing to carry it out.

5. Rapid heating systems

Heating systems which are able to introduce rapid or immediate heating

can seem tempting, however, sudden changes in air temperature can cause

serious problems for old buildings. The combination of warm air and still

cold surfaces causes air-borne moisture to condense on walls and windows

in particular, and the sudden rise in temperature causes rapid expansion

and contraction of the fabric of the building and its furnishings. Condensation

on the walls can also make the building feel more cold and damp, reducing

the effect of the heating system as well as contributing to any existing

problems with damp.

|

||

| Masonry repairs by St Blaise at Lyme Regis church (St Blaise Ltd) |

Because the buildings materials and construction techniques used in the past are so different from those used today, their conservation and repair needs to be left to those who have trained in this field and who specialise in this type of work. Being registered with a professional body such as the Royal Institution of British Architects (RIBA) or the Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors (RICS) does not mean that a professional consultant is qualified or experienced in conservation work, and building inspections are regularly carried out by professionals who have little real understanding of how historic buildings should be repaired. The appointment of building contractors in particular is a minefield as some highly experienced conservators have no formal qualification, while many others who claim to specialise in the field are both unqualified and unskilled. This is why so many buildings are damaged by poor masonry cleaning, use of the wrong type of mortar and other inappropriate routine repair work. However, the situation is gradually improving following the introduction of several accreditation bodies, listed below, and The Building Conservation Directory provides an excellent starting point for selecting appropriate specialists.

7. Unsympathetic alterations and repairs

It is obvious that alterations to update or accommodate new facilities will have a considerable impact on the character of an old building. The impact of smaller alterations and repairs, however, is more easily overlooked and often receives little attention at the design stage. For example, the introduction of new lighting in the interior may require electrical wires to be run in places where they have not been run before. If not properly planned, by the time valuable wall paintings or historic wallpapers are discovered under the plasterwork, a four-inch channel has been chased across them. Similarly, chasing conduit through roof timbers may result in structural damage, particularly if the timbers are already overloaded. The results can be catastrophic. In each case, no matter how small, consider:

- the need for the alteration

- its effect on the character and enjoyment of the building or component

- the archaeological and historical impact of the alteration

- its effect on structural performance and durability of the building or component.

Where the alteration of historically important fittings and fabric is unavoidable, the original or existing structure should be carefully recorded, before, during and after alteration, to provide a record not only of the building's history, but also of the alteration itself so that they can be quickly identified if any further modifications or repairs are required in the future.

ACCREDITATION SCHEMES

- Register of Architects Accredited in Building Conservation, 11 Oakfield Road, Poynton, Cheshire SK12 1AR Tel 01625 871458 www.aabc-register.co.uk

- Professional Accreditation of Conservator-Restorers (PACR), c/o Institute of Conservation, PO Box 444, Sigford, Newton Abbot TQ12 9DZ www.icon.org.uk

- Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors, Building Conservation Group, 12 Great George Street, Parliament Square, London SW1P 3AD Tel 0870 333 1600 www.rics.org/uk

PLANNING

LEGISLATION

In England and Wales planning is governed by the Town & Country Planning

Act 1990 and the Planning (Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas)

Act 1990, while in Scotland it is governed by the Town & Country

Planning (Scotland) Act 1997 and the Planning (Listed Buildings

and Conservation Areas) (Scotland) Act 1997. Further guidance is given

in separate documents for each of the three regions as follows:

- England: Planning Policy Guidance (PPG) 15 (issued in 1994) Scotland: Memorandum of Guidance on Listed Buildings and Conservation Areas (1998 edition)

- Wales: Welsh Office Circular 61/96, Planning and the Historic Environment: Historic Buildings and Conservation Areas; and the Welsh Office Circular 1/98, Planning and the Historic Environment: Directions by the Secretary of State for Wales.

Despite this disparity in guidance, the legislation governing the conservation of the built environment is in many respects identical throughout the UK. Unlike other buildings, some ecclesiastical buildings which are in use are exempt from many aspects of listed building and conservation area legislation, but not planning permission.