Seeing the Past in Colour

An introduction to architectual paint research for historic interiors

Lisa Oestreicher

|

Curiosity is endemic amongst professionals involved in the conservation and repair of historic buildings, including building archaeologists and historic paint analysts in particular. Fortunately, it is also a trait possessed by the owners of many buildings in equal abundance. The secrets held by the layers of paint which cover so much historic fabric provide tempting clues to the way the building or structure appeared to previous generations. The problem is how to unlock this information.

Often the presentation of architectural compositions such as the interior of a room seems confusing. The elements created in one period are presented according to the tastes of successive owners and occupiers, and the colours used by one generation may effect a very different character from that originally envisaged. Highlighting one surface in a particular way can also have a substantial impact on its relationship with other elements, affecting the architectural composition dramatically. Wall paintings and decorative effects such as trompe d'oeil wood graining and marbling may also have been used in the past, and there may have been physical alterations, such as the introduction or removal of panelling or a fireplace.

Interpreting how the room has changed can be difficult, not least because decorative schemes overlay each other, and can even co-exist in the same room. The key to unravelling this information is an architectural paint investigation. This process, which should be seen as an archaeological exercise, involves careful examination of all the available evidence, including archival records and the paint layers themselves, to build up a picture of the decorative evolution of the surfaces. However, investigations are often targeted to shed light on the decorative treatment in one specific period.

The information gathered in this way may be used to recreate a decorative scheme of a particular period, or it may simply be recorded for posterity. Where conservation repairs or investigation work necessitate the removal of the historic paint layers, as is sometimes necessary, the paint analysis and the archived samples may serve as the only surviving evidence of its decorative history, providing vital information for future generations.

Background research is an important component of a paint research project as it will give a context to the findings and it will help to determine where samples should be taken. Historic bills, contemporary descriptions or illustrative material all serve as useful sources of information. Such records might be found in archives held at the historic property itself or in local or national depositories. Oral history can also provide invaluable information: those who lived or worked at the property for many years often have insights into earlier uses and alterations not immediately apparent.

On-site investigations essentially involve the examination and analysis of surviving paint layers by a variety of different techniques, including cross-section analysis, and scraping back to expose the various layers.

The general rule of thumb when taking samples is that the greater the number and the larger the sample, the more information will be retrieved. However, this approach must be balanced against the sensitivity of the fabric. In the case of an interior, samples would usually be taken from each of the architectural features within a room and any sub-component that might have been decorated in a different manner. In a complex entablature for example, certain elements might have been gilded or highlighted in contrasting colour, so to gain a true understanding of how it was decorated, it would be necessary to sample all its constituent mouldings, and because each element is quite small, several small samples might be required. On flat surfaces such as large expanses of wall it may be possible to take larger samples, but they should still be taken from a variety of locations. This reduces the chance of sampling an unrepresentative area such as a wall where soft distempers have been washed down prior to repainting, or an area affected by a physical alteration. Where analysis reveals that substantial paint stripping has been carried out in the past, the results may be sketchy and extrapolation of the results may be required.

On an exterior surface which has been exposed to the elements, the chance of finding that previous layers have been lost is much greater, and sampling must focus on very specific points where old paint layers are most likely to survive.

For analysis, the samples are set in resin blocks, ground down to expose a cross-section through the paint layers, and polished. They are then examined in both incident and ultraviolet light to develop an understanding of the sequencing of decoration as well as the materials employed in their execution. Microchemical tests are also useful for determining the nature of the pigmentation and medium identified in cross-section. Further commonly available techniques for pigment analysis include polarising light microscopy, which helps to identify many of the mineral constituents of an inorganic pigment; electron dispersive X-ray spectrometry (using an electron scanning microscope) or Raman spectroscopy, both of which can determine the elemental composition of the sample. Gas chromatography-mass spectroscopy can also be employed to give more information on the medium involved in a particular decoration.

The identification of materials is important for gaining an understanding of the appearance of a decorative application and how it may have deteriorated over time. But certain materials, particularly pigments, also have dates of manufacture or introduction associated with them. When comparing these date markers with documentary evidence it is possible to establish a picture of how the room has changed over time.

COMMISSIONING ARCHITECTURAL PAINT RESEARCH

Since this is a relatively new area of conservation, not everyone knows how to commission a paint analysis programme in order to reap its full potential benefit. The most common misunderstandings concern the timing of paint analysis within a conservation project. If the investigations have been initiated strictly to gain further information on the development of a room as an end in itself, and the surfaces concerned are not about to be stripped, the research can proceed at its own pace without many outside constraints.

If, however, the results of the analysis will have a role to play in the planning of a conservation project or in the redecoration of a room, its role in the programming is more crucial. As paint investigations can be thought of as the archaeological portion of the project, it becomes clear that this work has to be done prior to actual conservation and building work. It should provide the first piece in the puzzle, shaping the approach taken to the conservation of the building and the way in which the fabric is presented.

|

|

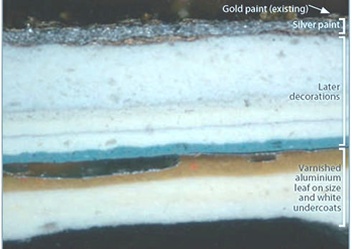

| Cross-section (above left) taken from the ceiling fish motif (above right) in the foyer of the Apollo Theatre, London. Currently embellished with details in gold paint, the sample confirms that the detail was originally entirely silver, with varnished aluminium leaf. The illustration at the start of the article shows another fish from this remarkable 1930s interior, which is now known to have been similarly altered. | |

Furthermore, it is worth bearing in mind when planning a conservation project that architectural paint analysis is a service offered by a relatively small group of properly trained specialists, and it may not always be possible to find one free at short notice. It is advisable to assess the need for paint analysis at the earliest opportunity.

To gain the greatest benefit from paint analysis and to avoid unnecessary costs it is important to develop a precise brief for the investigations. This process is best undertaken in conjunction with the analyst, so the abilities and limitations of the process can be fully explored and taken into account. For example, if it is an important component of the project to assess whether the cornice is original to the creation of the room, the paint investigations can be targeted to provide a timely answer to this question.

The analyst will also require as much historical background information as possible before commencing work. This will give him or her an idea of the best areas to take samples from, as well as providing the context within which the findings are placed. Most paint analysts are trained architectural historians and capable of undertaking such work, but in some instances it might prove more cost effective to have such historical information prepared in advance.

|

|

| Early 18th century marbling at Hanbury Hall in Worcestershire: the presence of an earlier trompe l'oeil scheme was indicated by cross-section analysis of paint samples, and confirmed by carefully scraping back the upper layers to reveal the composition of the scheme. |

Following historical research, the analyst will need to take small samples from the building. These may be removed before work starts on site but often further site visits are made as the project progresses, possibly once demolition or uncovering work has commenced. In this manner access can be provided to previously inaccessible areas. It is important that any access restrictions and scaffolding requirements are discussed at an early stage so that the investigations can be properly planned.

Once the samples have been set and examined microscopically, the process begins of marrying up the information gleaned from analysis with the information gleaned from the historical research.

The final product of a programme of paint analysis will usually be a small archive of resin-set samples and a report tailored to the brief outlining the conclusions drawn by the analyst. This report usually includes a section describing the paint layers or 'stratigraphy' of key paint samples, including the materials and methods employed. Another section then presents the conclusions with an account of the chronological sequence of individual decoration schemes, and setting out what has been discovered about the architectural development of the room and its decoration. It would also be expected that any specific queries raised in the brief are answered in this section. The explanation of the findings is normally assisted by the inclusion of photomicrographs, a sample list, sample location photographs and often tables charting the various schemes identified.

Following receipt of this report, it may be necessary to initiate a second stage of investigation in which paint layers are scraped back to uncover a specific decorative scheme, such as stencilling, to determine its pattern, or to reveal a particular paint colour so that the analyst can colour-match it. An understanding of the materials employed will give a good idea of how the paint finish may have aged, enabling the paint analyst to show the decorator how to recreate the original colour, without being misled by the current colour in its degraded state.

Ideally, the information contained within the report will help the conservation team (the architect, surveyor, curator and others) to solve conservation issues and guide them in choosing an appropriate model for presenting the final results to the owner or the public. As the report should also include a description of the materials and techniques employed, it may also be of assistance in determining a suitable conservation approach for the fabric. However, it is important to involve the paint analyst in these curatorial and technical discussions, as his or her understanding of the building's historical development and decorative techniques may be critical to the decisions eventually arrived at.

|

|

||

| Above left: Royal Victoria Park bandstand, Bath (1880s) as found. Above right: the bandstand after its redecoration. The colour scheme, which probably dates from the Edwardian period, was chosen because it was the one about which most could be discovered from the paint analysis. | |||

Finally, consideration should be given to where resin-set samples should be stored, as these may provide a convenient primary source of reference for future research, and if the surface from which they came is ever stripped, they will be the only primary source; unique, irreplaceable and invaluable. Larger organisations, such as the National Trust, may have their own repository but more often than not it is the paint analyst who will keep them for future reference.

Although there is always the risk that the analysis will reveal that substantial paint stripping has been carried out in the past, limiting the scope of the information gained, paint investigation is an exciting and important tool in the conservator's and curator's armoury. Based on sound analysis of the surviving paint layers (or archived resin-set samples) and thorough historical research, a paint analysis report should help them develop a clearer picture of how their building or interior evolved, and should enable them to make more informed decisions when considering its conservation and presentation.