Papier Mâché

Harriet Hawkes

|

Even though papier mâché was quite commonly used in interiors of the 18th and 19th centuries, both in conjunction with wallpapers and as a substitute for plaster mouldings, the extent of its survival is often not fully realised. Studies of more familiar materials such as plaster and wallpaper have eclipsed investigations into its use and conservation, and in any case it can be difficult to identify.

Papier mâché ornament can survive extremely well in stable conditions, but it is vulnerable to damage and, where paint removal is involved, failure to identify it can lead to spectacularly disastrous results – careful testing of cleaning systems is essential. Since no companies now manufacture papier mâché its conservation and repair can be problematic. Where sections of papier mâché mouldings are missing it is possible to remodel individual pieces to fit, but it can be difficult to match material mixes and methods of production.

Papier mâché is principally composed of pulped or layered paper that has been pressed into a mould, generally with a binder such as starch glue or oil, with perhaps the addition of whiting or gypsum fillers. Later variants include carton pierre – a pulp of paper with a high gypsum plaster content. The shallow relief moulded wallpapers such as Lincrusta and anaglypta or impressed panels of Tynecastle are close relations, and architectural papier mâché also has connections with the production of mirror and picture frames and japanware (imitation lacquer ware), where its use is better documented.

The more common fibrous plaster, which uses a fibrous mix to give added flexibility to gypsum plaster, developed out of papier mâché and some manufacturers, such as Jacksons, made a direct switch from one to the other. Another alternative – composition, or compo – also found favour during the late 18th-19th century mania for artificial materials. Unlike papier mâché or carton pierre, compo had no fibrous content but relied on the use of oils for its flexibility. Moulded rather like a putty, it was particularly popular for cast ceiling decoration.

|

HISTORY AND DEVELOPMENT

The

use of papier mâché in this country can be closely related to the first

widespread use of wallpapers from the late 17th century, which were made from

linen or cotton rag. It is generally accepted that much of the production of papier

mâché in Britain resulted from the paper hangers’ prudent use of off-cuts,

as papers were taxed per sheet through most of the 18th and earlier 19th centuries.

Early 18th century accounts of its production are rather scarce, but quite grand-scale

use of papier mâché mouldings – such as those at Walpole’s Strawberry Hill

– occur from about 1740 onwards, with quite a concentrated use corresponding with

gothic or rococo decorative schemes in the mid 18th century.

Papier mâché was used by the paper hangers to produce fillets which masked the edges of wallpaper pieces. In this respect the material made good use of their offcuts. Trade cards from some 18th century paper hangers – such as Masefield’s or James Wheeley of London – also offered a range of papier mâché mouldings to be used as an alternative to plaster or compo. The material was supposed to be more durable than plaster and, importantly, for vaulted gothic ceilings such as at Strawberry Hill, was lighter and less dangerous should there be a collapse. These ‘off-the-shelf ’ mouldings also allowed a client to select a whole decorative scheme at once and had – at least by the 19th century – the distinct advantage that they did not need to be installed by a specialist.

Geoffrey Wills and John Cornforth have demonstrated that frame makers also carried architectural papier mâché mouldings. But indications are that interior schemes using these papier mouldings were, for the earlier and mid 18th century at least, the province of the more well-heeled members of society, and it was not until the later 19th century and the advent of mass production that papier mâché came to be used for architectural detail in more ordinary households.

Surviving accounts of papier mâché from the 18th century indicate that the paper pulp method of production was the most usual. Alastair Laing quotes Lady Luxborough, for example, describing in 1751 how ‘the paper is boiled to a mash and pounded for a vast while, then it is put into moulds of any form.’ Pounding was necessary to achieve a uniform surface, without which the result would be an unconvincing imitation of plaster. The implication might be that pulped paper mouldings dominated this period of production. But exuberant mouldings reused in the estate church of Witley Court in Worcestershire, for example, are quite clearly made up through the layering of discarded paper sheets with a binder, and it seems that for most of the 18th century neither method of production dominated.

|

|

| Bielefeld mouldings fixed onto the beams of a coffered ceiling at Dinefwr, Dyfed | |

|

|

| Detail of an 18th century ceiling rose in a Sussex townhouse. Distinctive brown papier mâché can be seen inside the moulding with just discernable curled paper edges. This moulding is made from layered paperr pieces, but has not been mechanically pressed. |

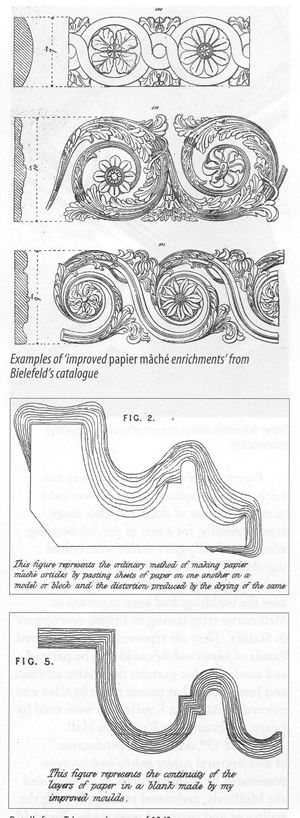

The relationship of architectural papier mâché production with that of japanned ware is less clear, although advances in production and patents relating to papier mâché seem largely to have been made by japanners such as Henry Clay in the 1770s. The heavily varnished japanned ware required an extremely smooth but durable surface, which pulped papier mâché did not consistently provide. This led to the introduction of what Clay patented as ‘best’ work, where layers of paper were applied alternately to either side of a piece of board, thus avoiding distortion through shrinkage. This method produced a robust and flexible panel which proved invaluable in interior fittings, but less so for the production of three-dimensional ornament. Patents exclusively relating to layered paper compressed into moulds suggest further refinements of papier mâché production continued along these lines until 1839, when JF Saunders patented Improvements in Certain Descriptions of Paper, Papier mâché &c. Capable of Being Produced from Pulp Paper. By the 1840s blanks of paper pulp made from off-cuts were being supplied direct to the makers of smaller papier mâché objects; predominantly wood-pulp papers rather than the linen or cotton rags of the 18th century. In 1815 Jennens and Bettridge had patented refinements for using both pulp and layered paper, but from the 1840s Charles Frederick Bielefeld came to dominate the production of papier mâché ornament, patenting not only the materials for the mouldings but also for the reproduction of the moulds themselves. Wear and tear on the moulds was considerable in 19th century papier mâché production, as manufacturers used mechanical presses, and Bielefeld’s patent included the use of iron filings in the mix to provide the necessary durability and resilience. His layered papers by this time were allowed to dry naturally, before being oil-saturated and dried a second time in stoves.

Papier mâché panel, however, was not solely used for japanned ware. It was used in the fitting out of ships and also, more experimentally, for a sort of pre-fab housing, where panels of papier mâché were bolted together. The Illustrated London News featured such a project by Bielefeld in 1853, reporting how the buildings had been exported to Melbourne after testing in British downpours in Staines. They are reported to have survived. Panels of papier mâché could also be painted and used in rather grander decorative schemes, and Jones notes that panels made by Clay and painted by Angelica Kauffmann were used by Adam, for example at Kedleston Hall.

By the 19th century the production of architectural papier mâché had become dominated by manufacturers in London and the Midlands, associated principally with the wallpaper and japanned ware trades. Bielefeld was London based and his production of papier mâché mouldings was so successful that he was able to produce catalogues for off-the-shelf purchase, giving the buyer moulding dimensions and even sectional views of the pieces to illustrate their profiles. His work in the Reading Room of the British Museum has most recently been repaired. At the same time, Jennens & Bettridge were producing catalogues of their papier mâché goods in the Midlands. Mouldings by this time varied from cornices and ceiling roses through to quite elaborate capitals, and ranged stylistically from medieval Gothic through to scholarly Greek: the original association with the 18th century gothic or rococo styles had been lost.

The reasons for the decline in the production of architectural papier mâché are hard to pinpoint. Innovations of Lincrusta in the 1870s and anaglypta in the 1880s allowed mass production of shallow relief using wood or cotton pulp and various binders on continuous canvas backings. Carton pierre, which used the quick-set of gypsum combined with the flexible fibrosity of paper, certainly became more popular by the later 19th century and was used to great effect in many theatres and early cinemas. It in turn was supplanted by fibrous plaster, which omitted the paper content in favour of individual fibre. The production of japanned ware simultaneously began to wane after a rather disastrous showing at the Great Exhibition of 1851 at which the japanners were held to have exhibited a singular lack of taste (architectural mouldings were also displayed), but also as electroplating replaced the vastly expensive and appalling working conditions of japanning. Experimentation with cast paper panels continued with the production of anaglypta and later Tynecastle, but papier mâché by then had all but disappeared. Architectural papier mâché ceased to be commercially produced by the middle of the 20th century.

CONSERVATION AND REPAIR

|

|

| Papier mâché mouldings and panelling at Baggrave Hall, Leicestershire | |

|

|

| Papier mâché ceiling decoration in the hall at Dinefwr, Dyfed |

The principal problem when dealing with architectural papier mâché is how to identify it. Horror stories abound about fireplaces and doors losing their mouldings together with their paint layers, when owners have been undertaking rather gung-ho paint removal. Early papier mâché is particularly difficult to identify as it tends not to have an oil content and, as a result, there is less likelihood of the telltale distortion inherent in most later types. Carton pierre and fibrous plaster are also difficult to distinguish from plaster mouldings – and from papier mâché – unless broken.

A close visual inspection will help. Papier mâché mouldings can appear quite flat in contrast with more three-dimensional lime plasterwork, but the same can apply with the more common composition work and distinguishing the two can be difficult. If access is possible, it may be helpful to tap the surface of the deeper mouldings: papier mâché will almost always sound hollow, unlike composition or gypsum. At the same time, look for evidence of fixings, particularly tack-heads, gaps between the mouldings and the wall or ceiling which appear to have been filled, or simple distortion of the moulding: most mid–late 19th century papier mâché has some oil content, and may appear distorted where polymerisation of the oils has caused the piece to contract slightly. Oils will also usually give the papier mâché a yellow or brown colouring.

Where breaks can be seen in the pieces, papier mâché mouldings will usually be hollow at the back, and where paper pieces have been used rather than a pulp to form the moulding, the material will be quite simple to identify. It can be hard to distinguish between papier mâché and carton pierre, particularly as some papier mâché was finished with a coat of whiting and size to produce a smooth surface of gesso which could then be gilded, and some carton pierre was applied on continuous paper backings. It is, however, relatively rare for papier mâché to be gessoed.

In several cases, the applied papier mâché ornament will be quite at odds with the overriding architectural style of the room in which it is used. Many 18th century schemes combine rococo birds with austere palladian doorcases or fire surrounds, or the mouldings appear over- or under-sized for the space in which they have been applied. Obviously such stylistic ‘mistakes’ do not guarantee the presence of papier mâché, but they can be useful indicators.

The hardness of oiled papier mâché is comparable to hardboard, whereas earlier papier mâché tends to be more vulnerable to damage or disintegration, but in either case pieces should only be eased back into position and held by light tacks; never forced. For missing pieces moulds can be cast as for plaster, but matching the material remains a problem. As methods of production were in continuous development through the 18th and 19th centuries, it is often unlikely that an exact match of either material content or method of production will be possible. There is, however, no practical reason why papier mâché should not be used rather than gypsum mouldings, and a number of specialist contractors will still undertake such repairs.

Recommended Reading

- J Cornforth, ‘Putting up with Georgian DIY’, Country Life, 9 April 1992

- Y Jones, Georgian and Victorian Japanned Wares of the West Midlands, Wolverhampton Art Gallery & Museums Exhibition Catalogue, 1982

- C Hind (ed), The Rococo in England, The Georgian Group, London, 1984

- A Laing, Foreign Decorators and Plasterers in England

- T Rosoman, London Wallpapers: Their Manufacture and Use 1690-1840, English Heritage, London, 1992

- G Wills, English Looking Glasses: A Study of the Glass, Frames and Makers (1670-1820), London, 1965

- C Woods, ‘Proliferation: Late 19th Century Papers, Markets and Manufacturers’ (England) in L Hoskins (ed) The Papered Wall, Thames and Hudson, London, 1994