Conserving Railway Heritage

Jim Cornell

|

|

| Bristol

Temple Meads Station: the main entrance, 1999 (all photographs by Railway Heritage Trust unless otherwise stated) |

Britain’s built heritage is as varied as any in the world. Its architects, designers and engineers drew upon centuries of experience to construct a huge variety of buildings and structures which provide an invaluable insight into much of the economic and social history of our land. All manner of materials have been used, including natural and local resources, those emerging from the industrialisation and, latterly, those produced by 20th century high-tech processes. These advancements together with developments in construction methods and design standards have led to an array of buildings, and to a lesser extent structures, which increasingly are becoming recognised as being of enormous value and interest to the nation.

RAILWAY HERITAGE AND ARCHITECTURE

Railway architecture, although all less than 200 years old, displays its own vast variety of features and components. The emergence of the steam railway in the early part of the 19th century had a great impact on civilisation and on industrialisation worldwide. Within less than 25 years, Richard Trevithick’s experiments at Coalbrookdale led to the opening of the Stockton & Darlington Railway in 1825. Without doubt, the 19th century was the age of the railway.

Between 1825 and 1875 the network of railways spread throughout the country as rival investors built competing lines. Although not always benefiting the business bottom line, and often duplicating both routes and facilities, the result united the nation, benefiting passengers and delivering freight to even remote parts of the country.

Some 9,000 stations, 1,000 tunnels and 60,000 bridges were constructed in addition to an enormous range of ancillary buildings such as warehouses, rolling stock housing and maintenance sheds, signal boxes, water towers, offices and hotels.

The first railway stations often reflected the local architecture and would not have looked out of place in the high street of any small country town. Local materials and styles were used, with speed and economy of construction being a major design consideration, and size was more often than not relatively modest. There were, however, a few notable exceptions including Neo-classical, Gothic or even Moorish-style buildings, perhaps intended as much to reassure the first nervous passengers as to impress prospective investors.

Leading architects, engineers and contractors were attracted by the fame and prestige, not to mention fees and salaries, which were associated with this new era of opportunity. The benefit to our heritage was a rich legacy of well-designed buildings and structures which has stood the test of time – 175 years in some instances.

|

||

| Settle Station in 2000, illustrating the distinctive features of the Midland Railway's design, with ridge tiles, barge boards, window and door frames appearing very much the same as when they were constructed in the mid 1870s |

The second half of the 19th century and the early years of the 20th saw tremendous growth in rail traffic. During this time the railways’ power and prestige were expressed in the many ambitious buildings and structures that were needed to handle the ever-increasing business. At the start of this period – the age of the Crystal Palace and the Great Exhibition of 1851 in Hyde Park – significant examples of pioneering structures were completed. Their building involved the use of what was then the latest technology and an unlimited supply of cheap labour; men prepared to live on the job in far from ideal conditions, who still produced generally high standards of workmanship. Excellent examples of such achievements include Dobson’s Newcastle Central Station, and Stephenson’s High Level and Royal Border Bridges.

While hardly anything physical remains of theGreat Exhibition, much of the railway infrastructure which brought millions of visitors to the Crystal Palace in 1851 still survives in daily use. Bristol Temple Meads, Paddington, St Pancras and Huddersfield railway stations compare favourably with our great country houses, cathedrals and public buildings. The great architectural practices of the day were involved; the hotel at St Pancras, for example, was the work of Sir George Gilbert Scott, famous also for the Albert Memorial in Hyde Park; while the Charing Cross Hotel was designed by Edward M Barry, the younger son of Sir Charles Barry who built the Houses of Parliament.

Civil engineers also played their part, with Brunel’s Royal Albert Bridge crossing the Tamar at Saltash and Robert Stephenson’s Britannia tubular structure over the Menai Strait in North Wales.

ARCHITECTURAL VARIETY

|

|

| Great Malvern Station: the capital of one of the platform canopy columns in 1998 |

It may not be readily apparent to today’s railway traveller that the lines were built by many different railway companies rather than by one entity. However, countless distinguishing features still survive which reflect the architectural house-style of a particular company and where the ravages of time have not taken their toll.

The Midland Railway’s Settle to Carlisle route illustrates this particularly well. This line was driven through some of the most demanding terrain in Britain. Doubts about the line’s future in the 1970s and ’80s, coupled with budgetary pressures, resulted in virtually all of the station buildings remaining in situ although lacking attention to maintenance. Some properties were even sold to private owners. Despite the lack of maintenance (since reversed), virtually all the distinctive features of the Midland Railway’s design remains, with ridge tiles, barge boards, window and door frames appearing very much the same as when they were constructed in the mid 1870s. The progressive restoration of all the buildings on the route is now bringing pleasure to those who travel by train and significant benefits to the local economy.

The design of the Midland Railway was distinctive, but it was also robust; a statement of intent and durability. Contrast that with the ornate style of Elmslie’s Great Malvern Station which is unique in minor station architecture. The wrought iron ornamental roof ridge and cast iron brackets give way to the most elaborate and richly decorated column capitals to be found anywhere on the rail network.

Of the largest stations, Bristol Temple Meads forms one of the most important assemblages of historic railway buildings anywhere in the world and is listed Grade I reflecting its architectural and historical importance. Brunel’s 1840 terminus gave way to Digby Wyatt’s 1874 building with its magnificent clock tower, delicate canopies and terracotta chimneys, and the complex also includes Brunel’s remaining passenger building, engine sheds and offices. Bounded by the City of Bristol’s new Temple Quays development to the north east, well over 160 years of architectural styles are present in a relatively small geographical area.

|

|

| Surbiton Station (J Robb Scott, 1937) in 1999 Photo: Milepost 92½ | |

|

|

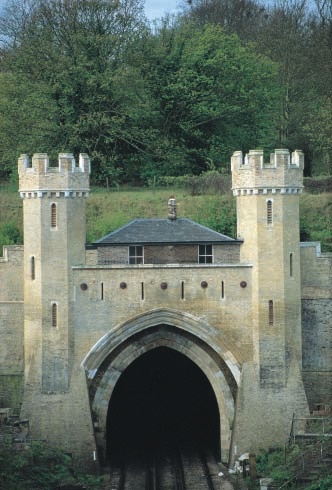

| Clayton Tunnel with its elaborate portal in 1997 Photo: Milepost 92½ |

Not all listed railway buildings date from the 19th century. Surbiton, probably the oldest suburb in Europe, owed its existence to the railway and grew around Kingston Station which opened in 1838. This station was quickly succeeded by Kingston Junction in 1845 (renamed Surbiton and Kingston in 1863) and the Southern Railway, in turn, replaced this with the present station in 1937. J Robb Scott’s attempt at the ‘International’ style has received mixed reviews over the years including one description as ‘flashy’. Pevsner, however, regarded it as 'one of the first in England to acknowledge the existence of a modern style'. Restoration works in recent years have confirmed the success of Surbiton’s elegant design features.

The builders of our railways did not confine imaginative design to stations and other buildings. There are numerous examples of extravagant designs which were applied to tunnel portals and bridges. Most people find the west portal of Brunel’s Box Tunnel near Bath amazing, but perhaps Clayton Tunnel’s north portal, on the London to Brighton line near Hassocks in West Sussex, surpasses even Brunel’s efforts. Dating from 1841, the portal comprises a massive two-centred arch surmounted by a headwall flanked by two hexagonal towers. Outside each tower a flanking wall extends to a small turret on each side, combining into one of the most elaborate tunnel entrances in Britain. To complete the extravagance, nestling between the towers stands a dwelling house, originally provided for the railway’s policeman.

Not too far away from Clayton Tunnel is John Urpeth Rastrick’s Ouse Valley Viaduct at Balcombe. Considered by many as one of the most elegant railway viaducts, it may owe some of its classical elegance to the distinguished architect David Mocotta. In addition to its slender brick piers it has stone balustrades and no less than eight stone pavilions. The original limestone came from Caen in Normandy but this source was exhausted by the time Railtrack PLC commissioned a four-year programme of repairs in 1996–7. Comparable stone was brought from Auxerre in France enabling this Grade II* listed viaduct to be fully restored to its 1841 splendour.

Through the post-war era right up until the early 1980s, the nation’s concern for its built heritage was far from a priority. Railway heritage was regarded in the same manner and the situation probably made worse as the industry lurched from one financial crisis to another.

The demolition of the Great Doric Arch at Euston in 1961 was an act that caused outrage and may well be regarded as a watershed after which the nation’s Victorian heritage, and its railway heritage in particular, assumed greater importance. It wasn’t until 1981 however, that the then Secretary of State for the Environment decided that a record of the rich heritage of historic railway buildings should be published, and the first volume was duly completed by the Public Services Agency. The British Railways Board, conscious of the interest and variety of British Rail's heritage, responded positively by establishing the Railway Heritage Trust in April 1985. The Board's view that a respected and maintained heritage complements an efficient and modern railway service was a welcome vision indeed.

DEALING WITH CONSERVATION

A major

challenge for the railway industry is finding solutions for historic buildings

which have become totally or partly surplus to operational requirements.

The problem applies to buildings rather than bridges; there are only 44

listed bridges within the non-operational estate.

|

|

| Newcastle Station: Bell's south barrel roof in 1997, shortly before the removal of the intrusive 1954 signalling centre/relay room |

Buildings, however, range from signal boxes, crossing keeper’s cottages and rolling stock maintenance depots to small, medium and large stations where, following the introduction of modern technology, productivity and re-organisation initiatives, their operational usefulness has reduced significantly or altogether. For example, the introduction of new signalling technology such as Solid State Interlocking or Radio Electronic Token Block can often result in one new signalling centre removing the requirement for up to 80 traditional signal boxes. The de-staffing of rural branch line stations and rationalisation of rolling stock maintenance depots have created unused space or totally empty buildings. Often the siting of such buildings, with their close proximity to the railway, imposes restrictions on reuse for safety reasons.

Following years of decline, demand to use the railway is increasing. 21st century customers usually welcome the historic environment provided by the variety of architecture on display to them as they use station buildings, but they rightly have 21st century expectations such as lifts, escalators, customer information systems, modern ticketing facilities, lighting and signage.

These modern requirements must be carefully balanced against the calls for minimum intervention and for alterations to be reversible. Clearly there is a need to respect the character and historic interest of our built heritage. The use by the industry of architects with conservation experience is essential if win-win solutions are to be achieved.

The Railway Heritage Trust’s remit can be effectively split into two parts. First, the focus is the conservation and enhancement of buildings and structures which are listed for their special architectural or historical interest or scheduled as ancient monuments. Second, the Trust acts as a catalyst assisting outside parties and the buildings’ owners on the conservation of non-operational property and securing alternative uses, including the possible transfer of responsibility to local trusts or other interested organisations.

How the railway industry, supported by the Railway Heritage Trust, attempts to balance conservation and business requirements is best demonstrated by examples.

Probably the most dramatic demonstration of reversing previous unsympathetic action is the removal of the 1954 signalling centre/relay room which had been driven through Bell’s south barrel roof at Newcastle. Following major engineering works, the steel framed intrusion was removed in 1998/99 and the splendid 1893 roof has now been fully restored to its original condition.

|

|

| A former water tank (1861) at Haltwhistle Station after restoration in 1999 |

Manchester Piccadilly Station is another example. By the late 1990s, a succession of uncoordinated initiatives, many severely restricted financially, had produced a hotchpotch of station facilities which neither met customer needs nor respected the buildings’ architectural and historic importance. Then an intensive three-year programme of work was commenced which led to a complete transformation of the concourse, the restoration of the train shed walls and former Goods Agents Offices and the dramatic ‘opening’ of the 1883 undercroft. All of this work now splendidly complements the earlier recladding of the train-shed roof in modern ‘planar’ glazing. Damaged capitals and filigree brackets of the cast iron train shed columns have been repaired and even a travelator has been introduced. Modern intervention has blended excellently with the 1883 construction in a massive and highly successful investment.

On a much smaller scale, and as a complete contrast, is the restoration of the 1861 water tank at Haltwhistle, including the provision of office accommodation within the red sandstone arched base as part of the Haltwhistle Regeneration Strategy. For almost two decades this structure had declined and been little used other than as a store for platelayer tools and materials. Restoration and reuse has delivered conservation through regeneration. Even the decorative castings on the water tank have been restored.

Reuse on a much grander scale occurred at Liverpool where the former London & North Western Railway’s North Western Hotel of 1871 was re-opened by John Moores University as student accommodation in October 1996. The hotel had closed in 1933 and for the next few decades the building was used as railway offices. After it was finally abandoned in the 1970s, its condition declined rapidly. This magnificent structure has now been fully restored, apart from a relatively small part of the ground floor, with significant works being carried out to the stairway and entrance hall. The University has taken out a 150 year lease on the building, thus conserving its future.

|

|

| The Doric Arch at Euston Station, London, which was demolished in 1961, shown in a watercolour of 1838 |

Most of the stations on the West Highland Line between Helensburgh and Fort William became unstaffed halts in the 1980s. Several of the stations which were built in the early 1890s are in a ‘Swiss chalet’ style with matching pavilion-like signal boxes and are listed Grade B. Bridge of Orchy was one such example. Only minimal use was being made of one small room until in 1998 an imaginative proposal was developed to convert the station into a 15-bed bunkhouse for use by walkers, fishermen, canoeists, skiers and tourists. The excellent conversion, including the restoration of dado panelling, window frames, doors and cladding ‘shingles’, was achieved through a five way partnership. The accommodation, now known as the ‘West Highland Way Sleeper’, sits on an island platform which still receives regular train services on this route. No building is too small to be brought back into use once it has become non-operational. A simple conversion has allowed a small business to take over the signal box at Torquay Station and this is just one example where determination by all concerned can ensure conservation in situ. It would be wrong not to give an example of the reuse of a non-operational railway viaduct to complete this short review of conservation and restoration works. Lambley Viaduct in Northumberland was designed by Sir George Barclay-Bruce and when it was opened in 1852 it was the only major feature on the Haltwhistle to Alston branch line. The branch closed in 1976 and over the next 16 years defects started to grow and the parapets were vandalised. British Rail Property Board assembled a group of partners to fund significant devegetation and repair works. The partners included the North Pennines Heritage Trust which, on completion of the works, took over the viaduct and opened it as a footpath and cycle way which links to the South Tyne Trail.

Historic railway buildings

and structures are important examples of our nation’s built heritage.

Significant efforts have been made over the past two decades to conserve

that heritage whilst at the same time responding to modern business requirements.

For further information please contact:

Railway Heritage Trust, 40 Melton

Street, London, NW1 2EE

Tel 020 7557 8598

Fax 020 7557 9700

E-mail rht@ networkrail.co.uk