Roof Lighting

Peter King

|

||

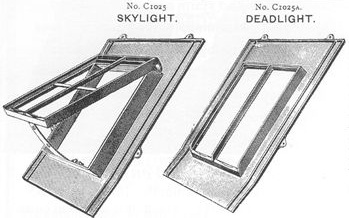

| Victorian cast iron rooflights from an original catalogue |

The appearance of roof lighting is a relatively recent occurrence in our architectural history. But flip through the pages of any architectural journal or view any urban area from above today and it will quickly become apparent that roof lights are now an important part of our architectural legacy.

It is difficult to find any large new public or commercial building without a prominent roof lighting feature and domestic roofscapes are often peppered with rooflights. This was not always the case. Roof lighting has gone from non-existence to ubiquity in the span of about 300 years.

In Britain and throughout most of Europe skylights did not appear until the mid 1700s when the developments in the process of glass manufacture made available relatively cheap glass sheets of adequate size. For rooflights, large panes which could span from top to bottom without a break were preferable, as small panes connected together by horizontal glazing bars (or lead cames) could invite leaks.

The earliest and simplest form of rooflight was a sheet of glass inserted into a tiled roof in lieu of a roof tile. This had the advantage of being relatively cheap, but it could not be cleaned easily, it was difficult to repair if broken and could not be opened to provide ventilation. Consequently this form of roof lighting was used primarily in secondary or agricultural buildings.

The earliest openable rooflights used in domestic architecture appear to have been timber framed with a lead-clad timber kerb and an opening casement (also lead-clad) which overhung the kerb on all sides. The lower edge of the glass would be left free of framework in order to allow rainwater to run off the rooflight quickly. Rooflights of this type can be still be found on some Georgian and Regency residential buildings, usually tucked away around a side or rear elevation in a position where a dormer window would be architecturally undesirable or physically problematic.

Rooflights did not become common in ordinary houses until the late 19th century, partly because excise duties, which were imposed on glass by weight in the mid 18th century, favoured small, thin panes of glass. Dormer and gable windows and lantern lights (in which the glazing is vertical) therefore provided the principal means of lighting attic rooms and staircases respectively, throughout the 18th century, and they remained so throughout the 19th century, long after rooflights had become common. Following the removal of excise duties in 1845, which coincided with a number of technological improvements in the manufacture of glass, there was an immediate and dramatic change in the appearance of windows as glazing bars were removed, and a less noticeable increase in rooflights, which remained functional necessities, often tucked out of sight.

Mass-produced rooflights of cast iron became available in the mid 19th century and their use in domestic architecture has continued up to modern times. Large-scale overhead glazing was achieved by means of the patent glazing which was similarly devised, developed and confidently used by the Victorians in all manner of structures from railway stations to museums.

By the late 19th century, glass had become relatively inexpensive and was available in good quality large sheets. The Victorians self-confidently built on a scale previously unheard of and with a collective panache and flair that has seldom been matched since. Building types that had never existed previously had evolved during this period, such as the great railway stations, which utilised vast areas of overhead glazing. Other deep-plan public building types of this time, such as the Leeds Corn Exchange and University of Oxford Museum, would not have been possible without the use of overhead glazing, and the most famous Victorian building, the Crystal Palace of 1851, employed glazing on an unprecedented scale.

In domestic buildings, original cast iron rooflights are most commonly found over the stairwells in late Victorian and Edwardian terraced houses. To reduce the draught caused by air circulating across the cold surface, these rooflights often had secondary glazing fixed at ceiling level.

THE FUTURE OF TOP-LIGHTING

Today, rooflights are more common and more popular than ever before, particularly in attic conversions and in refurbished historic buildings, where they are seen as a practical and unobtrusive means of letting light into roof spaces. Their popularity is due in part to the improvements made in the thermal and weathering performance of metal and timber rooflights which have brought the small-unit rooflight up to date, and they are also much less expensive to introduce than dormer windows (roughly 25%-30% of the cost), and size-for-size they admit more light. However it must be said that rooflights are still seldom seen as other than as a necessity in domestic architecture, and they take an architecturally subservient role to other elements. Rooflights have been and probably always will be seen in domestic architecture as a device to admit light and ventilation to a space as inconspicuously as possible.

Although top-lighting has become widespread in both the domestic and public realms, lighting from above is rarely used by designers for its own particular qualities. In domestic work it is generally used for utility purposes only, while in public buildings it is invariably ‘mixed’ with side-light. As anyone who has visited a top-lit gallery will know, natural top-lighting, when separated from side-lighting, generates in our country (with its almost permanent cloud ‘filter’) an ethereal, almost luminous effect. It may be that our eyes are used to seeing objects in side-light, and top-light – like theatrical low light – throws our senses slightly out of kilter.

The value of top lighting was widely recognised by 18th century architects like Robert Adam, who used lanterns over grand staircases and halls of grand houses and stately homes to great effect, establishing a tradition continued in buildings as diverse the Dulwich Picture Gallery and the Johnson Wax Building. Hopefully, apart from offering us economy and planning convenience, top-lighting through rooflights will, in the right hands, continue to bring us the unique sensation of light from above.