Wooden Churches of the Russian North

Richard Davies

|

|

| Church of the Virgin Hoddigitra (1763), Kimzha, Mezen district, Archangel region (All photos by the author) |

Christianity was formally established in what is now Russia in AD 988. In Nestor’s Primary Chronicle we are told that Prince Vladimir of Kievan Rus was urged by envoys from neighbouring countries to adopt their faith. He was tempted by the Muslim Bulgars’ promise of beautiful women in paradise but ‘circumcision and abstinence from pork and wine were disagreeable to him. “Drinking,” said he, “is the joy of the Russes. We cannot exist without that pleasure”’.

Vladimir eventually decided to be baptised into the Orthodox faith and, as the chronicles tell, he ‘ordained that wooden churches should be built and established where pagan idols had previously stood’.

Thousands of wooden churches were built all over Russia although many were later rebuilt in stone and brick as wooden churches became unfashionable. In the 1830s a German traveller noted that ‘the Russian country people take a particular pride in stone churches in their villages… nay its inhabitants would scarcely marry those of villages with wooden churches’.

However, in northern Russia, where wood was the most common building material, wooden churches were still being built up to the time of the Bolshevik revolution. The new and surviving ancient churches were often clad in white-painted boards and their aspen-shingled onion domes gave way to shiny metal ones to give the impression that they were spanking new stone churches.

|

|

| Church of St Dimitrius of Thessalonica (1784), Verknaya Uftiuga, Krasnoborsk district, Archangel region |

The north of European Russia grew prosperous over the centuries, exploited by the traders of Novgorod for its resources – fur and salt in particular. Its rivers and lakes were important trading routes and many settlements grew up beside them. Each town and village had its place of worship, traditionally not one building but three: a winter church, a summer church and a bell tower. Each city had its cathedrals and churches. Monasteries and hermitages were built on the islands of the White Sea, on the islands in the vast northern lakes and in deep forest.

Kholmogory and later Archangel, on the Northern Dvina River, were the most important ports of medieval Russia and trade with the English and the Dutch brought more wealth to the region. All this changed, however, with the building of St Petersburg by Peter the Great. With a port that remained ice-free for ten months of the year, St Petersburg became the window to the west and northern Russia became increasingly isolated and sank into obscurity.

During the mid to late 19th and early 20th centuries there was a revival of interest in the north, this time ethnographic rather than economic. Leading historians, musicologists, artists and architects travelled to the north. While working as an ethnographer in 1889, the artist Vasily Kandinsky described the peasants as ‘so brightly and colourfully dressed that they seemed like moving, two legged pictures’. In 1904 the artist Ivan Bilibin wrote of the bell tower at Tsyvozero, ‘she is living her last days, she has leant over sideways and trembles in the wind. The bells have been taken from her’ (110 years later she is still hanging on). The painter Vasily Vereshchagin complains, in 1894, of the neglect of the churches by the local clergy: I wish they had even a brief course in the fine arts at the seminaries. If priests who have responsibility for the old churches do not show mercy and unceremoniously demolish them, what can we expect from the semi-literate country fathers. They are ready to sacrifice every ancient wooden church for a gaudy new stone church, embellished with manneristic golden baubles.

If the custody of the wooden churches by the priesthood was shoddy, their custody by the local Soviets after the revolution was catastrophic. The artist Ivan Grabar and the architect and preservationist Pyotr Baranovsky joined the campaign to save the northern wooden architecture. In 1921 Baranovsky undertook the first of ten expeditions to the north to study its architecture: In the villages on the banks of the Pinega there were so many churches that were ‘extremely miraculous’ that I decided that come what may, I would go up the river to its very source. You arrive in a village and there are two or three tent-roofed church beauties, three-storey wooden houses, mill-strongholds – and all of them first-class architectural masterpieces… I don’t know anything more miraculous than Russian wooden architecture!... It is hard to acknowledge the fact that the descendants of those who raised this miracle with their calloused hands, destroyed the glory of their great-great grandfather’s father. And destroyed they were, no wooden church survives on the Pinega river today. Those that did survive in the north were used by the local Soviets as warehouses, grain stores, clubs, garages, dance halls and cinemas. Most were left to rot.

|

|

| Church of the Transfiguration (1781), bell tower (1793), Turchasovo, Onega district, Archangel region |

After the ‘Great Patriotic War’ against Nazi Germany and its allies, during which God had been reinstated by Stalin to fight on the side of Holy Russia, there was an effort to restore the wooden churches that had survived. They were recognised as a great symbol of Russian culture, the culture that the Russian people had been fighting desperately to preserve.

In 1948 the architect Alexander Opolovnikov (1911-1994) supervised the restoration of the wooden Church of the Assumption at Kondopoga. With his team and later with his daughter Elena (1943-2011) Opolovnikov restored over 60 monuments of wooden architecture and much of what we see today, including the churches at Kizhi and the Cathedral of the Assumption at Kem, survives thanks to them. Opolovnikov also produced technical drawings of the churches and of their construction details that are great works of art.

With the break-up of the Soviet Union, funds disappeared and most restoration came to a halt.

STOPPING THE ROT

The first wooden church I visited, in 2002, was the 43-metre high Church of St Dimitrius of Thessalonica at Verknaya Uftiuga. I later learned that Alexander Popov, a student of Opolovnikov, and his team had spent seven years from 1981 to 1988 restoring St Dimitrius. They had completely dismantled the church, rotten timbers (15% of the whole) were replaced and then the building was reassembled log by log. The logs were up to 12 metres long and some weighed as much as two tons. Popov, like Opolovnikov, is very rigorous in his research and methods and at Verknaya Uftiuga he experimented with the local blacksmith to produce carpenters’ axes based on sketches of axe heads found by archaeologists in Siberia. He was keen to use the same techniques and tools as the builders of 1784.

In 2011 I asked Mikhail Milchik, vice director of the St Petersburg Research Institute of Restoration and a great expert on Russian wooden architecture, to write an afterword to Wooden Churches: Travelling in the Russian North. He was not optimistic, his first sentence read, ‘Wooden Architecture, the most original and most unique part of the cultural heritage of Russia, is on the verge of extinction’.

Almost four years on I’m slightly more confident of its survival (I hope Mikhail is as well). I have one or two reasons for believing this. Firstly, I am very impressed by the grassroots organisations that have been set up to record what has survived and other organisations that have been established, often on a very local scale, to do what they can to literally stop the rot. Water ingress is the main enemy of wooden buildings. When the joints are rotten, collapse is imminent. Local people have taken it upon themselves to repair the roofs of their churches and bell towers, to shutter windows and to clear out the detritus of years of neglect.

|

||

| Local carpenters Alexei Malofeev and Mihail Mahnov at the Church of the Transfiguration, Turchasovo | ||

|

|

|

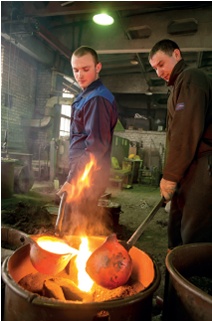

| Above left: restorer Sergei Golovchenko, Turchasovo. Above right: new bells being founded for Turchasovo at the Shuvalov Bell Foundry, Tutaev, Yaroslavl region in April 2015 | ||

The organisation Obscheye Delo (Common Cause) was founded by Moscow priest Father Alexei, who spends his summers at Vorzogory on the White Sea with his family. He explains: When we first came here we suddenly heard the unexpected sound of an axe splitting wood by the abandoned bell tower. It was Grandpa Sasha, for years he had been patching and repairing the tower – he simply couldn’t bear the thought of it one day collapsing before his eyes. We were so inspired by his example, that we immediately offered our help and now, every summer, we work to restore the ancient temples of Vorzogory. Obscheye Delo has set itself the task of saving the wooden churches of northern Russia. Each summer its members, now in their hundreds, patch leaky roofs, prop up walls, clear undergrowth and dig trenches to act as firebreaks. Professional restorers will take their place in time but many of the churches and chapels being patched up by volunteers are having their lives extended for a few more years.

Money has been made available from private and public sources to restore churches. Alexander Popov is now working on restoration of the early 18th-century Church of the Saints Cosmo and Damian, near Lezhdam in the Vologda region. It had been sitting neglected in the woods for many years but has now been dismantled and transferred to Popov’s workshop in Kirrillov. Another example is the 17th-century Church of St George. Also abandoned in the woods, it was discovered beside the Northern Dvina River in the Archangel region in 1997 by the artist Ivan Glasunov. The church has now been professionally restored and re-erected at the Kolomenskoe Museum of Architecture in Moscow.

The Church of the Transfiguration (1781) at Turchasovo was in the process of restoration during Soviet times but that came to a stop with the break-up of the USSR. I first visited the church in March 2006, when the snow was thick on the ground. The church and its bell tower stood magnificently above the frozen sweep of the Onega River. Svetlana the churchwarden opened the church for us, warning ‘Don’t stand under the dome, the birds will drop something revolting on you’. The windows were shuttered and it was dark inside as Svetlana told us about Alexei Sioutine, who works in Norway but whose mother was born in the village. He is trying to raise funds to finish the restoration and to hang bells once more in the bell tower.

When I visit again in 2010 the timber window shutters have been replaced with plastic sheeting and our need for care is clear to see. Svetlana is saying prayers in the church every day, others sometimes join her and she is encouraging the children to take an interest in and to respect their church. By 2012 the guano has been replaced by a plastic sheet, the church has been cleaned with the help of the children and the restorer, Sergei Golovchenko, and others are working on the roof, cutting out the rotten wood where possible and laying down new timbers to keep out the wet. There is much to do and the village women have set up a canteen in a building donated by the community to keep the workers fed and tea’d.

In 2013, with Alexei Sioutine, we climb up through the mass of church timbers and out onto the roof to meet local carpenters Alexei Malofeev and Mihail Mahnov, who are continuing the work to make the church watertight. We look down on the bell tower, which still needs a set of bells, and over the great curve of the Onega River.

Alexei tells us that the work he is doing is illegal – the church belongs to the state, but the state is doing nothing, so if not him, then who? He can’t stand by and see it collapse before his eyes – another Grandpa Sasha. If I remember right the ageing sign stating that the church is under the protection of the state was still attached by a rusting nail or two.

I plan to visit Turchasovo again this summer, the bells have been cast and they will ring out again over the Onega River for the first time in over 80 years.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to acknowledge the help of Matilda Moreton (co-author of Wooden Churches), Daryl Ann Hardman (co-founder with Richard Davies and Cathy Giangrande of the charity Wooden Architecture at Risk) and Alexander Moshaev (co-author of Russian Types) in the preparation of this article.