Early 20th-century Shops

Lindsay Lennie

|

|

| Gill’s of Crieff blends traditional design with 1930s style, as in its Vitrolite stall-risers. |

While we undoubtedly admire the beauty of Victorian and Georgian shopfronts, it is some of our 20th century examples which are architecturally the most daring and striking. Inter-war shopfronts offer a particularly rich addition to our townscapes but are sometimes unappreciated and their designs and materials not always understood.

THE 1925 PARIS EXHIBITION

While many Edwardian shopfronts were beautifully constructed of exotic hardwoods and polished brass, they remained of an inherently similar design to their Victorian cousins. However, the 1925 Paris Exhibition was to be a watershed for 20th century shopfront design.

The Exposition Internationale des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Moderne firmly established the Art Deco movement while promoting revolutionary styles and new materials. Designs produced for the exhibition by French architects such as Louis-Pierre Sezille and Rene Prou were breathtaking in their bravery. The angular windows, daring signage and smooth frontages left visitors to the exhibition in no doubt about the radical new direction which retail architecture would take.

DESIGNS AND DESIGNERS

From this embryonic beginning in Paris, the style spread rapidly and by the mid 1930s its use in Art Deco-inspired shopfronts was widespread throughout British towns. Undoubtedly the large cities had the greatest number, with Glasgow particularly favouring a Moderne style. Kenna (1985:4) describes this as ‘consumer Art Deco which did much to brighten up the Depression-stricken city’. However, the style is also evident in smaller towns, often associated with butchers and fishmongers.

|

||

| Sunrise motif to shopfront clerestory, Falkirk: The design was popular in the 1930s and was widely used in shopfront design. | ||

|

||

| Tooth Factory, Forfar: A traditional shopfront with margin panes to the clerestory glazing, curved glass and black granite stall-riser (Photo: Historic Scotland) |

Leading architects like Joseph Emberton (1889-1956) were inspired by visiting the Paris Exhibition and mapped the way forward with their exciting new designs. Some, like Erno Goldfinger (1902-1987) took the ideas to minimalist extremes. Architects recognised that shops offered a particular opportunity to bring Art Deco to the very centre of people’s lives, to the main shopping streets of Europe.

By the end of the 1920s, two main types of shopfront style had emerged. The first was a very minimalist, undecorated design constructed of sleek and shiny materials. The second was of a more traditional style using curved glass entrances, leaded glass to the clerestory and marble or tiled entrance floors. There was therefore something of a reluctance to totally abandon the past. The use of stained glass to create sunrise motifs was popular for both shops and domestic properties. Others adopted leaded glass, sometimes with mock bulls-eyes or tracery bars and margin lights to decorate otherwise plain glazing. Inevitably, styles merged, changed and adapted to create a myriad of variations within the streetscape.

Whether Moderne or more traditional in inspiration, common features included geometric detailing, integral blinds, decorative stall-riser vents and window screens. These screens were timber and glass which focused the view of the customer on the goods in the window but still allowed light into the shop.

Although it was architects who experimented with the first undecorated shops, it was shopfitters who brought these new designs to the mass market. Firms like Frederick Sage, E Pollard & Co and Harris & Sheldon were leading designers of exceptional shopfronts which broke the mould of traditional shop design and construction. They re-fronted shops and offered specialist services such as showcases and interior fittings. They paid little heed to Victorian or Georgian parent buildings and were sometimes severe in their execution. The pursuit of a fashionable frontage surpassed any consideration of the surroundings.

Shopfitters were highly innovative and developed new products for their ever increasing client base. E Pollard & Co, for example, promoted a non-reflective glass in the 1930s. This was installed in the new black Vitrolite shopfront of T Fox & Co of London. Complete with a red neon sign, the shopfront was the height of fashion for this umbrella business which was established in 1868.

MATERIALS

During the early part of the 20th century the introduction of new materials like steel began to influence the construction of shopfronts. Steel allowed even more possibilities than its 19th century predecessor, cast iron. The construction of Selfridges in 1909 with its innovative steel frame and exterior of Portland stone heralded a new approach to department store construction.

While structural considerations were clearly crucial, it was the exterior finishes which created the necessary look. The last two decades of the 19th century witnessed the mass production of decorative tiles for the first time. While these remained a popular material for shopfronts into the 20th century, other materials crept into the market and gradually usurped these decorative ceramics. Cladding in marble, terrazzo and Vitrolite became a quick and easy way to transform a shop from traditional Victorian to Moderne overnight.

A browse through Perry’s 1933 Modern Shopfront Construction indicates the great breadth of materials available to shop designers in the 1930s. Travertine marble, black granite, Roman Stone (a form of artificial stone), bronze, embossed glass, walnut and stainless steel. Green marble proved to be particularly fashionable and was widely used. These materials were used in endless combinations to allow either a minimalist, Art Deco-inspired or more traditional style.

|

||

| West Coast Fisheries, Ayr: 1936 black Vitrolite shopfront. Some damage is evident but overall the Vitrolite is in fair condition. The fascia signs are particularly good examples of their type (Photo: Historic Scotland) | ||

|

||

| Former Burton’s store, Dumbarton: The ground floor shops have been altered and although the upper facade of white faience remains intact, the overall effect is lost (Photo: Historic Scotland) |

Of all of these, it was Vitrolite which became the iconic fashionable material of the 1930s. It is described in Pilkington’s Vitrolite Specifications as:

A Rolled Opal Glass ranging from semi-opacity to complete opacity. One surface is usually impressed with a pattern of narrow parallel ribs which provide a key for the mastic or other material with which the glass is fixed. The glass has a hard, brilliant, fire-finished surface.

There were 16 colours available, ranging from the standards of black, white, green and turquoise to more exotic shell pink and walnut agate.

Although its origins were as a practical material for use in hospitals and also to clad the Mersey Tunnel, it was a particularly versatile material for re-fronting shops. Available in a range of sizes and thicknesses, the opportunity to use different colour combinations and to utilise it with other materials such as chrome allowed a mass produced material to offer significant individuality. While many shop owners opted for a simple, classy look of black Vitrolite, others were more daring, creating innovative and striking designs inspired by the geometric style of the Art Deco period.

Other fashionable glazing products included etched or sandblasted glass. The use of opaque glass was not new. In the Edwardian period the use of delicately etched glazing, often for entrance doors, offered an air of elegance and sophistication to shops. The name of the shop owner or their trade reinforced the advertising of the business. However, during the 1930s the use of decorative glass was particularly popular for the clerestory of the shopfront. Geometric designs such as zigzags or wavy lines became an integral part of the shopfront design.

Faience and terrazzo also rose in popularity. These modest, unassuming ceramic materials provided a smooth finish and clean lines. Some retailers, like Montague Burton particularly favoured faience. His tailoring empire used white faience for its purpose-built inter-war shops designed by their Leeds architect, Harry Wilson. The gleaming white ceramic combined with Art Deco detailing to give a truly modern look for their shops. Chain stores like Burton’s made an important contribution to the promotion of these new materials and styles and were often at the cutting edge of shop design.

PROBLEMS

The great architectural success of these shopfronts was also perhaps their weakness. They were so modern and striking that their fashion was short-lived and by the time World War II had ended, the desire for this type of shop was waning. The 1950s saw a continuation of some of the themes born in the 1930s, but with less vigour and enthusiasm for the radical designs. Many shopfronts were replaced, making way for the designs which prevailed in the post-war decades including the rising use of aluminium.

Those which have survived face a number of issues. First, 1930s shops tend to be extremely sensitive to inappropriate alterations. Their minimalist style means that the overall architectural composition is surprisingly easily destroyed. Alterations to signage, entrances and windows can seriously detract from the designer’s original intention. In contrast, Victorian shopfronts are often more robust and seem able to withstand a greater degree of intervention while retaining their integrity. For purpose-built shops such as those erected by Burton’s, although the upper facades generally remain largely intact, the ground floor shops rarely survive, losing the overall design effect of the building.

|

||

| Bronze stall-riser vents set in green marble: These small details are important. Bronze vents varied in style but were always integral to the overall design. Damage to the marble is also evident. |

Secondly, a lack of understanding of the rarity or significance of these shopfronts means that they are extremely vulnerable. Although there is a greater appreciation of them now and statutory measures offer some protection, many outstanding examples have already been lost. In cities like Glasgow, where the streets were once brimming with Art Deco shopfronts and gleaming Vitrolite, finding good surviving examples is a challenge. Effort needs to be focused on ensuring that any shopfronts which remain are suitably protected and conserved.

Undertaking conservation, however, can be a problem. Some of the materials, once mass produced and readily available, are no longer manufactured. Vitrolite has not been produced since the 1960s and although there are some limited salvage options it remains a very rare material. This is a significant issue when dealing with a product which is subject to breakages and cracking, particularly at stall-riser level and around entrances where impacts can easily damage the glass.

Substitutes are rarely successful as they lack the depth of colour and distinctive finish which is characterised by Vitrolite. Shop owners have tended to resort to a mixture of unsatisfactory repair options including painted plywood, painted Perspex or glass and even polished slate. Damaged panels can allow water ingress, which may affect the stability of panels.

Options may include moving surviving panels to more visible locations and using a substitute material where the panels are less obtrusive. However, care needs to be taken in the removal of the panels to ensure further damage does not occur and that panels are made watertight when reinstated.

Other materials like faience and terrazzo are also subject to cracking and damage but they can, at least, be repaired more easily than Vitrolite. Similarly, matches are possible where marble cladding has become damaged or lost.

FUTURE CONSERVATION AND REPAIR

It is ironic that some of the more recent shopfronts cause the greatest conservation challenges. While repairs to Georgian joinery or Victorian cast iron shopfronts are relatively straightforward, the conservation of inter-war shops presents a much greater problem. The lack of expertise in dealing with them, together with the limited availability of certain materials means that shops frequently go unrepaired or are poorly repaired with inappropriate materials.

|

||

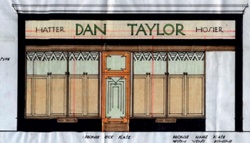

| Dean of Guild drawing for Dan Taylor’s Hat Shop, Perth, 1932 showing etched glass and window screens (Photo: Perth & Kinross Council Archives) |

Recognising the significance and rarity of these shopfronts is a vital starting point in ensuring that their place in the architectural time-line of shops is secured. Statutory protection also has a vital role to play.

The simplicity of inter-war shopfront design means that the special combination of integral blinds, door style, glazing pattern, stall-riser vents and fascia lettering should not be underestimated. Where features have been lost, reinstatement should be considered, where appropriate. Historic photographs and archive drawings can be particularly helpful in identifying the original features and design intentions.

Art Deco was a style which transcended localities and retailers. From tiny market towns to cities and from independents with a single shop to chain stores with hundreds of sites, the adoption of Art Deco as a style for shopfronts was unsurpassed. Despite the loss of many examples, the UK’s high streets remain more interesting places as a result of the Vitrolite, faience and terrazzo shopfronts which still survive. Their role in the architectural history of our towns and cities deserves better recognition and wider appreciation.

~~~

Recommended Reading

- T Draper-Stumm and D Kendall, London’s Shops: The World’s Emporium, English Heritage, London, 2002

- F Hudd, ‘Issues Surrounding the Conservation of Vitrolite Glass’, Journal of Architectural Conservation, Vol 16, Issue 2, 2010

- R Kenna, Glasgow Art Deco, Richard Drew Publishing, Glasgow, 1985

- R Kenna, Old Glasgow Shops, Glasgow City Archives, Glasgow, 1996

- L Lennie, Scotland’s Shops, Historic Scotland, Edinburgh, 2010

- K Morrison, English Shops and Shopping, Yale University Press, London, 2004

- T Perry, Modern Shopfront Construction, The Technical Press Ltd, London, 1933

- Pilkington Brothers Ltd & British Vitrolite Company Ltd, Vitrolite Specifications, Pilkington Brothers Ltd, London, undated (1930s)

- A Powers, Shop Fronts, Chatto & Windus, London, 1989

- The US National Park Heritage Preservation Services, Preservation Brief 12: The Preservation of Historic Pigmented Structural Glass (Vitrolite and Carrara Glass), Technical Preservation Services, Washington DC, 1984