Shutters

Linda Hall

|

|

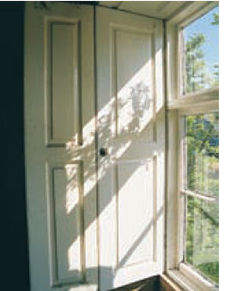

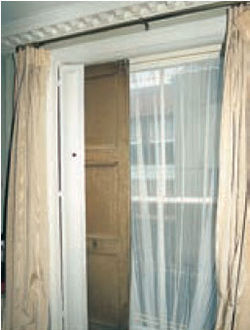

| An extremely rare example of sliding shutters: this window in the hall of a late 16th century manor house in Norfolk is a projecting oriel window, so it would always have been glazed. |

Shutters are a vital if often overlooked feature of many historic houses. In the medieval period, when most windows were unglazed, shutters kept out wind, rain, insects and birds. In later periods, when houses had cosier rooms with fireplaces and glazed windows, shutters provided extra draught-proofing and privacy. The common use of fastening bars with security devices implies that shutters were also regarded as protection against intruders. External shutters also protected windows from vandalism, and were common on the ground floor windows of vulnerable buildings like public houses, at a time when glass was expensive.

It is rare to find shutters dating from before the late 17th century and most date from the 18th and 19th centuries. They are perhaps the least-studied feature of historic houses and our knowledge of their dating and development will remain limited until more research has been done. Many have been covered with so many layers of paint that they no longer open, while others have been brutally stripped of all paint using blowtorches and the like, exposing pine panels that were never intended to be seen. However, many house owners who appreciate their historic value also attest to their usefulness in making houses warmer and more secure, so the shutter is far from obsolete.

|

|

||

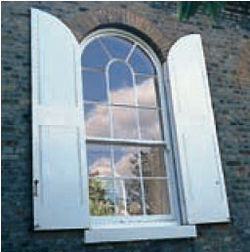

| Above left: panelled shutters in a house at Latteridge, South Gloucestershire (1686) with a second leaf of just three inches wide, yet fully panelled. The small iron bar on the sill is pushed through the iron hasp on the central mullion to hold the shutters closed. The edge of each shutter is cut away to accommodate the hasp. Above right: the outer face of these shutters at a house in Sproxton, Leicestershire (1810) have fielded panels, while the inner face, hidden when the shutters are open, has plain recessed panels. Often the narrower central leaf, concealed when the shutters are folded back, is a plain plank. | |||

EARLY EXAMPLES

Medieval stone buildings had hinged shutters whether or not the window was glazed. An early example is the Queen's Chamber at Guildford Castle, which in 1245 had glazed windows with opening casements and internal shutters. Other entries in the Liberate Rolls of Henry III (1232- 69) refer to shutters of fir, some painted with the royal arms; others in Cambridge in 1432 were oiled (Salzman, p255-8). Construction was the same as for doors, with planks, ledges and battens. Few have survived intact, but the pintles on which they hung often remain. Many were closed by a wooden or iron bar passed through a substantial iron hasp set into the central mullion; sometimes the stonework is expanded at this point to provide a hole for the bar (illustrated right).

Timber-framed buildings had either hinged or sliding shutters, and many had both. Hinged shutters could be hung to open sideways or upwards; the position of surviving pintles and hasps (for fastening), or the holes for them, will show which type was in use. Grooves for sliding shutters survive above the windows in the main horizontal timbers of many medieval and 16th century houses. The base of the shutter was usually held in a separate timber nailed to the face of the wall, although occasionally the sill was wide enough to contain the runner (Martin and Martin, p77). When these shutters went out of fashion, applied rails were taken down to allow for the removal of the shutters, so these rails rarely survive. However, the timbers below a window often still display the telltale marks of nails or, less commonly, peg holes showing where the rails once were. The upper grooves, usually about 25mm (one inch) wide, have sometimes been filled in with plaster and painted over, or hacked off altogether leaving a rough surface or an unexplained rebate.

|

|

| Medieval stone window from a farmhouse in Meare, Somerset with typical evidence of long-lost shutters: iron pintles for the hinges survive in the jambs, and the expanded portion in the centre of the mullion would have held a small iron bar to fasten the shutters |

Less common are vertically sliding shutters, often used where space was restricted or where there was a continuous run of windows. A document of 1519 refers to 'many pretty windows shut with leaves going up and down' (Salzman, p256) , and one has been reconstructed at the Weald and Downland Open Air Museum near Chichester. Wooden pegs or some sort of rope and cleat arrangement would have held the shutters fully or partially closed. Grooves for vertical shutters can be seen on the first floor of the Guildhall, Thaxted (Essex) and the top floor of the three-storey Chantry House, Henley-on-Thames, probably built in the late 15th century, which had a continuous run of windows facing the river.

17th CENTURY DESIGNS

Some evidence suggests that from the later 16th to the later 17th century the increased use of glazing may have caused shutters to be abandoned (Martin and Martin, p75). Oriel windows added to Priory Cottages, Steventon, Oxon in 1570-71 were glazed but retain no evidence of shutters, although another building of 1571 near Chesham, Bucks had sliding shutters throughout, with unglazed windows at the back and oriels, presumably glazed, at the front. However, little research has been done on this, and the extent to which shutters were used in the 17th century is not clear.

Evidence for hinged shutters is easily overlooked as it may be as slight as the presence of holes in the side or top members of the window where pintles (the hooks on which the hinges hang) have been removed, or nail holes left by simple butterfly hinges (Martin and Martin, p81-3). Many houses may have had external shutters, which remain common in Europe and America. However, surviving examples, which are more common in towns, appear to date from the 18th or early 19th century, and iron shutter stays on the outside wall are evidence of shutters now gone. These can be highly decorative, although English examples seem to be plainer than American ones, which are placed at the bottom of the shutter; in England they are more likely to be part way up the long sides.

|

|

| A medieval unglazed window in a farmhouse at Pebmarsh, Essex with a shutter groove in the horizontal rail above: damage and a peg hole below the window show where the bottom runner for the sliding shutter has been removed |

Shutters comprising two panelled leaves hinged together appear in the 1680s. Early examples survive at The Wardenry, Farley, Wiltshire, which was built in 1681 with large wooden-mullioned cross-windows. The shutters fit within the mullions rather than passing over them, and the upper lights are unshuttered. Each shutter has two leaves of equal size, joined with decorative H-hinges, with mouldings around each panel. Iron bars fastened to the outer frame swing up to overlap in a large open hasp on the central mullion, holding the shutters closed.

Commonwealth House in South Gloucestershire, dated 1686, has shutters covering the entire stone cross-window, with unusual methods of fastening and construction. The shutters are composed of two leaves each; the central leaf is only about 75mm (three inches) wide, yet is fully panelled to match the main leaves. There is no internal architrave or boxing and the shutters simply fold into the window reveals which are only slightly smaller than half the window width. This explains the very narrow central leaves. To hold the shutters closed, a small iron bar, 6mm (a quarter of an inch) square in cross-section, is passed through an iron hasp set in the central mullion.

GEORGIAN SHUTTERS

The design most commonly associated with Georgian houses, in which internal shutters fold back into architraves to form the window reveals, was common throughout the 18th century and until the 1840s. The main leaves are panelled on the outer face to form a panelled surround to the window. The fielded panel is common in the 18th century, with plain recessed panels or flush panels in the early 19th century.

|

||

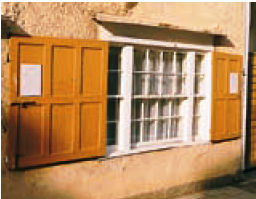

| External shutters in Holywell Street, Oxford with stays near the top of each side, and a central bolt for fastening the shutters together when closed. This would have to be done from inside the house by raising the sash window. If external shutters were used with earlier casements, they could only have been fastened on the outside, as English casements, unlike European ones, always open outwards. |

The number of leaves depends on the width of the window; two panelled leaves and one extra leaf is a common arrangement. This third leaf is usually a plain unadorned plank, and all the leaves are rebated to fit tightly together. Others have two leaves each side, both panelled, while some have one leaf on one side and three on the other. In this case the third leaf is a simple narrow plank, while the second one is panelled but to a simpler design than the main leaves. It has been suggested that so many shutters were required in the 18th century that specialist joiners mass-produced the main panelled leaves to standard sizes. Adjustment to the width of the window was made on site, hence the plain central leaves (Ayres, p73). This assumes that window heights were more standardised than their widths, although no statistics are available to confirm this.

Decorative H-hinges and butterfly hinges were used in the late 17th and early 18th century, superseded by plain H-hinges or rectangular hinges. Service rooms such as dairies had plainer plank shutters with strap hinges. Some shutters were split horizontally, allowing the lower half to be kept closed for privacy with the upper half open for light and ventilation. Sometimes panels are pierced with ovals, circles or hearts to allow a small amount of light in even when closed.

Sliding shutters were occasionally used, either sliding horizontally out of the wall on one or both sides of the window, or rising vertically from the sill; the latter are called sash shutters. Sometimes all that is left are the grooves on either side of the window, with pulleys at the top to take the sash cords. They tend to be found where the walls are relatively thin, or when a brick skin has been laid over an older timber-framed wall, leaving a thin gap, as at the Old Vicarage, Cheam, Surrey.

By the ascendancy of Queen Victoria in 1837, curtains had become more fashionable. Shutters were no longer used in the grander houses, although they continued to be used in smaller houses with front gardens through the 1840s, and they remained popular in street-fronting terraced houses until well into the 1860s.

|

|

|

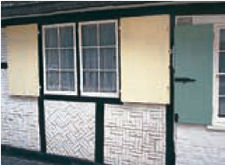

| External shutters on casement windows in Sandwich, Kent: the pair on the left are plank shutters of uncertain date, with stays halfway up the sides; on the right is a shutter with early 19th century flush moulded panels. | External shutters in The Close, Salisbury: these have central locking bars as used on internal shutters. Where there is no gap between the shutters, the bar doubles as a stay holding two adjacent shutters open. The outer ones have small stays on the outer edges. |

SHUTTER FITTINGS

Shutters were held closed by various forms of iron bar; usually fixed to one shutter while the other has some form of housing for it. The bar hangs down vertically when not in use. Crudely carved recesses in the opposite shutter leaf accommodate the projecting parts of the ironwork when the shutters are folded back. Some windows have removable bars held in hasps on either side of the frame. The simplest form of attached bar is a long hook which engages in a loop. Longer bars were used in the Queen's Bedchamber at Kew Palace, dating from c1720-30.

In theory, an intruder could raise the bar from the outside by passing a knife or other implement through the gap, although the rebated ends of the leaves should make this difficult. Nevertheless many shutter bars have some form of security device to prevent this. A County Durham house of 1752 has a bar which passes over a hasp and is held in place by a small iron pin attached to the end of the bar by a length of chain. More common, and generally later, are the press button and swivel fasteners. The latter have a small bar suspended from the fixing plate of the housing, which has to be swivelled to one side to allow the bar to be opened or closed. Most are plain, but there are a few beautifully decorated examples.

Press button fasteners have a concealed tongue within the housing which engages a hole in the end of the bar; a press button below the housing releases the pin. In another version found at a Sussex house of circa 1809 a decorative plate holds the bar; a projection on its inner face engages a small hole in the end of the bar and is released by pressing the base of the plate. Similar devices at Kew Palace, however, have been dated to the late 19th or early 20th century.

Other variations involve bars set diagonally; one has split shutters with one diagonal bar on each, with open hasps to hold the ends. A house in Bury St Edmunds has split shutters, with the bar split to form an elliptical shape to hold both shutters closed. The fact that so much ingenuity was expended on making shutters secure from outside penetration suggests that burglary is not just a modern phenomenon, and more variations are still being discovered.

|

|

||

| Above Left: External shutters are common on chapels and meeting houses, as here at the Friends' Meeting House, Brentford (1785). These have decorative S-shaped stays halfway up each side. 1785 seems early for flush panels, so the shutters may be later replacements. Above Right: Early 19th century horizontal sliding shutter from a house in Whitby: on each side of the window a shutter slides out from a hole in the wall, concealed behind a hinged flap which forms part of the window architrave when closed. | |||

~~~

Recommended Reading

- James Ayres, Domestic Interiors: The British Tradition 1500-1850, Yale University Press, London and New Haven, 2003

- Linda Hall, Period House Fixtures and Fittings 1300-1900, Countryside Books, Newbury, 2005

- Nathaniel Lloyd, A History of the English House from Primitive Times to the Victorian Period, 1931, The Architectural Press, London, 1975

- David Martin and Barbara Martin, Domestic Building in the Eastern High Weald Part 2, Windows and Doorways, Hastings Area Archaeological Papers, Robertsbridge, Sussex, 1991

- Steven Parissien, The Georgian Group Book of the Georgian House, Aurum Press, London, 1995

- Louis Salzman, Building in England Down to 1540: A Documentary History, 1952, Sandpiper, Oxford, 1997