Statements of Significance

The View from Historic England

Andrew Brown

|

| The churchyard of St Thomas à Becket, Box, Wiltshire: the monuments, the churchyard and its surroundings have obvious aesthetic value, but their broader and more complex values can also be captured in a good Statement of Significance. |

All our responses to historic places are conditioned by the values we attach to them, including which elements of our perceived inheritance we choose to protect, what we are prepared to fight for and what we are willing to let go. That is why the use of a values-based approach to the management of change in the world around us, due in large part to the success of The Burra Charter (1979), is embraced by Historic England.

Historic England’s preferred system of values is set out in the 2008 English Heritage publication Conservation Principles (see Further Information), which identifies four categories of heritage value – evidential, historical, aesthetic and communal – that together amount to the significance of a place. This approach draws heavily on The Burra Charter and the work of the late James Semple Kerr. Historic England commends this system of values to anyone proposing change to heritage assets because it allows the effects of change on what matters about a place to be set out clearly and any harm to be assessed.

A statement of significance is one of a number of formats in which the values attached to a heritage asset might be set out. Conservation Principles explains that:

A ‘statement of significance’ of a place should be a summary of the cultural and natural heritage values currently attached to it and how they interrelate, which distils the particular character of the place. It should explain the relative importance of the heritage values of the place (where appropriate, by reference to criteria for statutory designation), how they relate to its physical fabric, the extent of any uncertainty about its values (particularly in relation to potential for hidden or buried elements), and identify any tensions between potentially conflicting values. So far as possible, it should be agreed by all who have an interest in the place. The result should guide all decisions about material change to a significant place. (Paragraph 82)

Before expanding on this concise exposition of the purpose and content of statements of significance, however, it may be helpful to put them into the context of other similar documents and to clarify the differences.

Heritage impact assessments, as espoused for example by ICOMOS in relation to world heritage sites, tend to follow the method used for environmental impact assessments. The level of the assessment is usually the whole heritage asset, which is given a degree of importance on a scale from local to international according to its statutory designation. The effect of proposed change on that heritage asset is also classified on a scale ranging from negligible to major. Tabulation of importance against effect allows the impact to be classed as anywhere from major adverse to major beneficial. This approach, however, does not lend itself to the assessment of small-scale change such as alterations to a listed building.

Heritage statements are related to but distinct from either statements of significance or heritage impact assessments. They have become increasingly common as a result of the following requirement in the National Planning Policy Framework (NPPF):

In determining applications, local planning authorities should require an applicant to describe the significance of any heritage assets affected, including any contribution made by their setting. The level of detail should be proportionate to the assets’ importance and no more than is sufficient to understand the potential impact of the proposal on their significance. (Paragraph 128)

Many local planning authorities (LPAs) refer to this paragraph when requiring applicants to submit a heritage statement as part of their applications. A heritage statement not only addresses significance but also identifies impacts and then goes on to justify those impacts. Some LPAs call this a ‘statement of significance and impact’. While it is sometimes helpful for applicants to offer their own appraisal of impact, the onus clearly lies with the LPA (NPPF 129) to make its own assessment of the significance of any heritage assets affected and the impact of the proposed changes.

Historic England has found that a heritage statement which merges the assessment of significance with the impact assessment is rarely of much use in the decision-making process, as the exposition of the significance can become skewed in anticipation of justifying the proposed changes. Arguably, a more effective way of promoting sustainable development would be to encourage applicants and their agents, having first set out the significance of the asset(s) concerned, to describe clearly what changes they propose to fabric, spaces and views as part of a design and access statement. Such a statement explains and justifies the design decisions taken in the preparation of a development proposal in the round and not just in relation to heritage interest.

The efficacy of this approach is recognised in the Planning Practice Guidance (2014):

Design and Access Statements provide a flexible framework for an applicant to explain and justify their proposal with reference to its context. In cases where both a Design and Access Statement and an assessment of the impact of a proposal on a heritage asset are required, applicants can avoid unnecessary duplication and demonstrate how the proposed design has responded to the historic environment through including the necessary heritage assessment as part of the Design and Access Statement. (‘Conserving and Enhancing the Historic Environment’, Paragraph 12)

Better use of design and access statements would, in the view of Historic England, be the single biggest improvement in the operation of development management in relation to the historic environment. The most helpful design and access statements incorporate an assessment and justification of the impact on an asset’s significance (the ‘heritage assessment’), but retain a distinct statement of significance as a precursor, rather than it being part of the design and access statement.

|

|

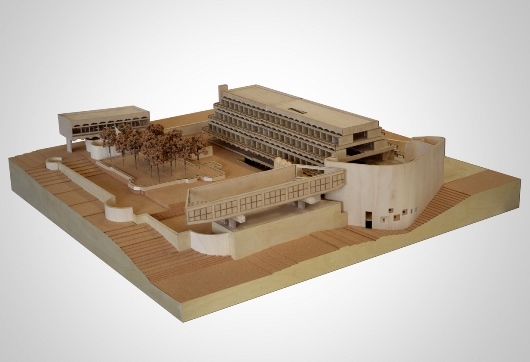

| St Peter’s Seminary, Cardross, Argyll (Photo: NORD Architecture, courtesy of NVA) |

Having set out what a statement of significance is not, it is timely to return to what it is. From Historic England’s perspective, a statement of significance is the tangible product of the process of assessing significance. A statement of significance very deliberately excludes any sort of impact assessment or justification for proposed changes because it should have a long shelf-life (although it should be reviewed from time to time), enduring beyond the exigencies of a particular scheme.

Avanti Architects’ conservation assessment of St Peter’s Seminary at Cardross (see Further Information) for the Archdiocese of Glasgow is an example which emphasises the ‘neutrality’ of a statement of significance – its independence from any specific proposed changes. Similarly, The Faculty Jurisdiction Rules 2013 explain how a statement of significance enables the potential impact of proposals on the significance of a place of worship to be understood – it does not itself deal with impact.

At the heart of any statement of significance is the articulation of why a historic asset matters to present and future generations. The four categories of heritage value set out in Conservation Principles can be useful as headings:

- evidential value – what potential for new knowledge is there in the fabric of the asset?

- historical value – how does the asset or its features support a narrative of the past?

- aesthetic value – how do people engage with the asset emotionally?

- communal value – how does the asset bring people together as a community[1]?

Not all assets will be valued in all four ways. Most assets in private ownership are likely to have relatively little communal value for example, so there is no benefit in grasping at straws to say something under each heading. Nor is it sufficient, however, simply to tick the box – for historical value, for example. Unless the parts of the asset and its setting that give rise to the value are identified, the statement of significance will be of little help to anyone.

It is essential to consider the setting of an asset as well as the asset itself when compiling a statement of significance. What goes on around a heritage asset can both affect its significance and the ability of people – today as much as in the future – to appreciate its qualities. This dual role of setting needs to be included in any assessment.

The best statements, therefore, are those which put their finger not only on what matters about a place for present and future generations but also how those values are manifested in the asset and its setting.

As for length, a statement of significance can sometimes be distilled onto a single side of A4 paper but more typically might run to two or three sides, especially if crucial features or views are illustrated to assist the reader. Longer statements can reflect a lack of precision or indicate the inclusion of superfluous information. Of course, large and complex heritage assets are likely to require longer statements than small and straightforward ones. Links to web-based supplementary information such as full National Heritage List for England entries are preferable to large blocks of pasted-in text.

The acid test of whether a statement of significance is fit for purpose is whether it facilitates conservation – the process of maintaining and managing change to a heritage asset in a way that sustains and, where appropriate, enhances its significance. And enhancement is where this brief discussion should conclude. Unlike any previous English planning regime, the NPPF explicitly encourages the appropriate enhancement of heritage assets and not merely the limitation of harm. Paragraph 137 of the NPPF, for example, invites local planning authorities to favour proposals which preserve those elements of the setting that make a positive contribution to or better reveal the significance of the asset. By articulating the value of heritage assets, statements of significance can be a springboard for designing change that provides future generations with a legacy from both past and present.

~~~

Further Information

Avanti Architects, Conservation Assessment: St Peter’s Seminary, Cardross, 2008

English Heritage, Conservation Principles: Policies and Guidance for the Sustainable Management of the Historic Environment, English Heritage, London, 2008

Department for Communities and Local Government, ‘Conserving and Enhancing the Historic Environment’, Planning Practice Guidance, 2014

Notes

[1] This is commonly confused with the utility value of a heritage asset, such as the use of a historic park for dog-walking which may be unrelated to the asset’s heritage qualities.