The Taylor Review

Diana Evans

|

||

| The Taylor Pilot has helped Beyton Parochial Church Council (PCC) to apply for a grant to repair All Saints Church in Suffolk, including the replacement of five broken coping stones on a very low tower parapet. The church has previously struggled to find a contractor due to its height and the extremely low parapet, making safe access a problem. (Photo: Historic England) |

The Taylor Review: Sustainability of English Churches and Cathedrals is nearly two years old and we are halfway through the pilot project exploring some of its core recommendations. The Taylor Review might have been buried or ignored because it didn’t appear to provide the radical new solution that so many had been hoping for in terms of future sustainability, but the government, in particular the Department for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport (DCMS), was committed to taking it further. Set up to focus on the Church of England (primarily parish churches rather than cathedrals) it recognised the reality of the situation that the places of worship sector found itself in, which was not rosy in December 2017.

The government-sponsored Listed Places of Worship Roof Repair Fund had injected £55 million into buildings in need between 2015 and 2017, but the fund was spent and everyone knew it would not be repeated. Subsequent evaluation by ERS Research & Consultancy showed that even £55 million could only fund 26 per cent of the total value of the applications made to it. Also during 2017 the Heritage Lottery Fund (now National Lottery Heritage Fund) announced that it would not continue the Grants for Places of Worship programme it had run since Historic England’s earlier withdrawal from the Repair Grants for Places of Worship scheme that both organisations had operated together. This was the end of dedicated places of worship grants that had, in various iterations, contributed nearly £500 million since 1996.

At the same time there was increasing emphasis on places of worship being accessible to, and available for, nonworship activities. All funders seemed to be moving away from capital grants for repairs to keep the buildings fit for purpose towards community based activities. This approach offered hope to congregations with a clear vision for such changes and enough volunteers to develop proposals that attracted funding. However, it had the effect of depressing those in small but active communities trying to keep a building going. It also frustrated denominations and congregations who believed they were custodians of sacred space, that could not be used for a farmers’ market or creative play zone.

The changes in funding culture also opened up a linguistic gulf between people of faith and the administration of grants. According to the Statistics for Mission 2017: Social Action survey, 80 per cent of Church of England congregations collectively offer their communities more than 33,000 social action projects, but they don’t articulate these in terms that ‘tick the boxes’ for funding applications; instead they talk of them in terms of service, outreach and compassion because those are the words that make sense in a faith context. Consequently, these often appear to potential funders as evangelistic (and therefore ineligible) rather than for public benefit per se. Being so enormously active also means that congregations find it hard to demonstrate that the outcome of any funding will be that more community engagement will take place and that a demonstrably increased number of people will value their heritage. In any case, congregations just don’t ask for that sort of feedback, their attitude is one of welcome and offering, not evaluation and monitoring.

|

||

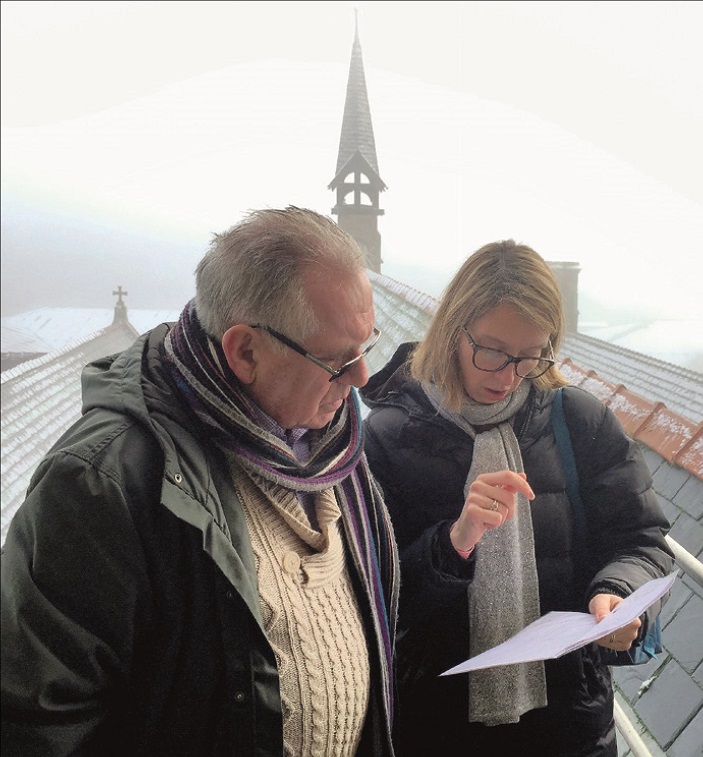

| The fabric support officer for Suffolk provides advice on minor church repairs and maintenance, and is pictured here with the churchwarden for All Saints Church in Beyton, inspecting the building and discussing a maintenance plan. (Photo: Anne Harrison) |

This isn’t to say that funding should not challenge congregations to use their buildings creatively and more regularly. At the very least every place of worship should be unlocked and accessible daily, if only as a haven for the harassed or heritage-hungry. Even insurers recognise that this reduces, rather than increases the risk of damage or theft because the possibility of someone just walking in on nefarious activity deters those with malicious intent. There will be some buildings where hate crime or other local issues mean that an open door in daylight hours isn’t prudent, but it is a fair principle that if the wider population contributes to the building through philanthropy, lottery-playing or taxes, then they should have access to it.

Taxation is in itself a two-edged sword for places of worship. On one hand this is a major source of income through gift aid recovery on donations (over £90 million a year for the Church of England alone) and the welcome 2016 increase in the Gift Aid Small Donations Scheme for cash gifts up to £8,000 a year simplified claiming for congregations. On the other, the levying of VAT on repairs and maintenance, but not new work, is a major burden on those trying to care for places of worship. Since 2001 the government has provided a VAT refund scheme which has repaid £275 million to listed places of worship but, valuable as that is, the scheme is retrospective and invoices have to be paid before claiming, so it can cause a cash-flow challenge. There is growing concern that the commitment to this funding ends in March 2020. This is causing congregations anxiety, particularly those with major building projects that will continue beyond that date, which will be applying for match-funding grants assessed on the basis that full VAT refunds will be available.

This is the context in which The Taylor Review was published. Its recommendations were not a silver bullet but prompted government to fund a pilot project that could explore the nuanced application of experience that The Taylor Review suggested. The pilot is open to all faiths and denominations, not only Church of England congregations, in the two pilot areas: Greater Manchester and Suffolk. These areas were chosen to enable as broad a range of buildings, congregations, faiths, denominations and locations as possible to participate, but the pilot is structured in exactly the same way in both. DCMS asked Historic England to manage the delivery but it is a partnership project, with an advisory board chaired by DCMS and strong national and local co-working promoted.

DCMS has also appointed an independent evaluator, Frontier Economics. This is a major step forward in a fragmented and diverse sector. Unlike museums and many other parts of the cultural arena, places of worship have never collated verifiable data sets. This meant that the Taylor Panel had to wade through a wide range of evaluation formats for different schemes, most of which offered lots of qualitative narrative but very little quantative measurement. By the end of the Taylor Pilot there will be new baseline data, greater understanding of the value of assessment and insight into how to demonstrate the value of investment in, and the public benefits provided by, historic places of worship. There may also be some guidance as to how congregations can achieve this through better articulation of their achievements (outputs, outcomes, impact) in the future.

|

||

| As a result of the pilot, the church of St Paul, Peel in Salford has been offered a grant for proposed works subject to obtaining the necessary permission. A realistic maintenance plan will also be developed. (Photo: Historic England) |

The pilot picks up on several key recommendations from The Taylor Review but has not been able to include a major repair grant scheme, simply because it would be impossible to deliver it in the 18 months before the pilot ends in March 2020. There is a minor repairs fund, which will distribute £1 million in grants of up to £10,000 for urgent maintenance or small repairs. This is to incentivise the crucial work that, if left undone, can lead to the preventable decay that has such a negative impact on historic fabric. Advice about minor repairs is provided by a fabric support officer, who makes a site visit and helps congregations to understand the value of stitch-in-time works and draw up an annual maintenance plan. Where appropriate the officers can also advise on applying for a pilot grant.

The Taylor Review strongly endorsed the prevailing view that local support is crucial if buildings are to be sustainable, not only in terms of financial contributions but also volunteering of skills and willingness to use the building in new but appropriate ways. The pilot will test this assumption: does increasing footfall and making people feel more welcome actually result in greater income and more practical help to keep the building in good repair?

The pilot provides community development advisers who can encourage congregations to forge new links and build on the hospitality already offered. The advisers can also flag up issues in the local plan, or opportunities for funding if community infrastructure levy money may be available. Most of all, the advisers can help to identify unexplored local needs that would be very close to the congregation’s own vision of ministry: the ‘knit and natter’ group that is now too big for someone’s home; the council meeting that can’t fit into the village hall schedule but could use the vestry; the drop-in venue for the local police team.

Some congregations will be affronted at the suggestion that they are not at the heart of their community already but there are very few that have explored all possible networks and developed every mutually beneficial relationship. It’s important to remember that some congregations either won’t be able to share their worship space in this way (although they may have other premises that can be used), are already doing everything possible given their resources and the local needs, or are simply in an area where community space is not in demand.

There are approximately 332 listed places of worship in Greater Manchester and 533 in Suffolk so the fabric officer and community adviser in each area would never be able to support them all. In an attempt to widen the access to the pilot messages, 16 workshops have been offered to provide basic information: six on maintenance, six on community engagement and four on planning and managing projects, whether those are repairs or changes to the building. Workshops were not part of The Taylor Review recommendations but were incorporated into the pilot as a way of increasing its potential outreach and to enable peer-to-peer learning, building capacity and a sense of not being the only one facing the challenges common to historic places of worship.

|

||

| Sixteen workshops have been made available to widen access to the pilot’s messages, covering maintenance, community engagement and planning and managing projects. This workshop took place at Bolton Victoria Methodist Mission. (Photo: Historic England) |

This approach was taken in the light of very positive feedback from the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings’ two HLF-funded projects, Faith in Maintenance and Maintenance Cooperatives, that used workshops as a key element in project delivery. Historic England’s support officers working with places of worship have also found them a good way of sharing best practice and building confidence. The evaluation of their impact in the pilot will be important: if they attract a wider range of faiths and denominations than pilot staff can reach in person then they are clearly an important element of reaching those who take responsibility for these buildings.

It is too soon to tell if the pilot is touching the people who most need what it offers – the ones who are unlikely to sign up for a workshop, ask for help or apply for a small grant. Since September 2018 over 200 places of worship have made contact with the pilot staff and 136 site visits have taken place, but special effort is being made to connect with those people facing the greatest challenges and those most reluctant to seek support.

The length of the pilot is constraining. Eighteen months is a very short time in which to achieve all the objectives and the pressure on the staff involved is considerable. In Suffolk there are logistical issues because of the size of the county. In Manchester the age of the buildings, their size and complexity means that access issues make even a basic repair, such as replacing a few slipped slates, disproportionately expensive.

The need to communicate the fundamental message that maintenance really matters is already clear in both areas. Historic England has commissioned a separate small research project to explore the value of maintenance in the context of deterioration over time and the recognition that, in the end, even the best cared-for materials come to the end of their lives. The research is in progress but we hope it will provide credible information to demonstrate that, even if the scaffolding costs more than the repair, there are real cost benefits to sorting out those slipped slates. If it does, that’s a message for the whole heritage sector.

The Taylor Review was a bold initiative and the government responded very constructively to it. The pilot is certainly making life rosier for some congregations in Suffolk and Manchester and will hopefully provide inspiration to many more in the future and lead to longerterm national initiatives.

Further Reading

Department for Culture, Media and Sport, The Taylor Review: Sustainability of English Churches and Cathedrals, 2017

ERS Research & Consultancy, ‘National Heritage Memorial Fund: Listed Places of Worship Roof Repair Fund Evaluation, Final Report’, 2017

The Church of England, Statistics for Mission 2017: Social Action, The Church of England Research and Statistics, 2018

Topmark (LPOW), ‘Listed Places of Worship Trust’, 2014, www.lpwscheme.org.uk/

Historic England, ‘Taylor Review Pilot’, 2019, https://bit.ly/2C41sh1