Thatch Fires

Marjorie Sanders

The risk of fire in thatched roofs is an issue that owners and others ignore at their peril. If the causes are properly understood and the appropriate measures taken, the risk of one occurring is low. However, it is clear that not all owners are aware of the risks they are taking.

Of the 50,000 to 60,000 thatched properties in the United Kingdom, approximately 24,000 are listed. Nationwide monitoring of thatched fires shows that during the 1990s 60 to 70 serious thatch-roof fires were recorded annually, and the figure is rising. Already in 2006 (to the end of April) over 70 have been recorded and documented. With few exceptions, these have all occurred in older, usually listed properties. The figures include domestic dwellings and a number of historic pubs, and 95 per cent are chimney-related.

This rise is paralleled by the increasing use of multi-fuel stoves, sales of which were running at an all-time high at the end of 2005. Although it is counter-intuitive to believe that the two are related, the installation and regular use of a multi-fuel stove or open fire with a flexible metal liner can seriously increase the risk of a fire. This is because modern enclosed solid fuel appliances are designed to burn efficiently and cleanly at high temperatures. Connecting these to old chimneys makes the thatch especially vulnerable to the risk of slow char caused by the build-up of heat through the brick and into the thatch.

|

|

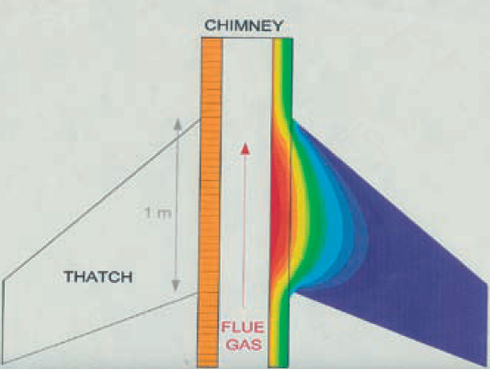

| Thermal transmission from an ordinary brick chimney into thatch: The colours show the temperature contours through 115mm of brick. Where the thatch surrounds the chimney, the insulating effect of the thatch prevents heat loss from the brick outer surfaces in contact with the thatch. If the flue gas temperature is maintained at 300°C, the chimneybreast above the fire is barely warm to the touch. However, where it passes through the thatch the temperature rises, and in an area where the thatch is around one metre deep, the bricks will heat through to the point where the temperature will be high enough to ignite the thatch after about 14 hours. The deeper the thatch, the greater the risk. |

Properties most at risk are those with deep multi-layered thatch surrounding a central chimney which has single-brick walls. Thatch separated from the flue by the width of just one brick, as is the norm in older thatched properties, can reach 85 per cent of flue gas temperatures after only one day of continuous use. Modern flexible metal chimney linings, even if faultlessly fitted, do not significantly reduce the temperatures achieved through heat transfer into the thatch. Badly fitted and inappropriate liners constitute a higher risk than no liner at all and fitting too large an appliance for the size of property also increases the risk. The risk is totally dependent on how the consumer uses and understands the heating system. Temperature monitoring can be carried out remotely by fitting a device (Thatchgard for example) in the area of the thatch which is most at risk, and enabling the effects of a stove to be better understood and controlled.

Traditionally, combed wheat reed and long straw thatch is maintained by fixing new spar coats on top of existing thatch layers. This gives the poured on 'chocolate box picture' appearance much loved by traditionalists. With time, the depth of thatch increases and, where the thatch abuts a chimney, depths of 1-2 metres can easily be reached. In this way, a considerable surface area builds up against the chimney making the thatch more vulnerable. The recommended clearance from the ridge to the top of a chimney stack is 1.8 metres (six feet). However, even a cursory review of the most picturesque villages will show many properties with thatch now level with the top of the chimney. Just building a chimney extension makes the situation worse as it allows even greater increases in thatch depths in the future.

It is therefore recommended that, when re-thatching, the opportunity is taken to remove old wire netting and reduce the thatch depth. However, removing old thatch is a controversial step to take. No thatcher willingly strips a roof, as it is hard, skilled, dirty and expensive work and disposal of discarded material is becoming an increasingly difficult environmental issue. Furthermore, the surviving thatch layers not only contribute to the character of the building, but they may also contain important archaeological information about the crops grown in the past and the way the building was used. Nevertheless, some removal is essential, and to keep thatch depth in proportion only the most recent layers need to be removed. In this way archaeologically significant material may be left intact.

Where removal of thatch is necessary, whether as a precaution against the risk of fire, or for structural reasons, such as to enable timbers to be repaired or replaced, thatch layers can always be recorded and samples stored as they are removed. In all cases it is essential to consult with all interested parties before removing existing layers of thatch, including the local authority conservation officer.

Buildings thatched in water reed are less vulnerable than those thatched in combed wheat reed or long straw, because when re-thatching occurs, water reed is usually removed and cleaned back to the rafters. (It is only likely to be spar coated in the West Country.) Water reed stems are tough and packed more tightly together, making them less flammable than cereal straw.

|

||

| House with deep thatch. This house in Hampshire has had numerous spar coats and the thatch depth has increased progressively. Originally, the top of the chimney pot would have been around 1.8 metres (six feet) above the ridge, and the thatch around it is probably about 2.4 metres (eight feet) thick. The installation of an enclosed multi-fuel stove employing this chimney would result in a high risk of fire. |

Fire risk is well managed in those new homes which are now being built with thatched roofs, as experience gained from studying old thatched buildings has led to the development of built-in fire prevention precautions. These include chimney flues being insulated and double skinned to ensure that there is no contact between thatch and the heat from hot flue gasses. In addition, the thatch is separated from the house by a fire resistant barrier, so, in the unlikely event that it does catch fire, the thatch becomes sacrificial, while the occupants and the rest of the house are protected from extensive damage.

It should always be remembered that thatch is an organic material, subject to different behaviour patterns depending on its surroundings, treatments and choice of materials or styles. It has a finite life span, measured in tens rather than hundreds of years and, above all, it is combustible.

Heat transfer is the most common cause of thatch fires in the United Kingdom. It is the combination of deep thatch and a central chimney in conjunction with the use of multi-fuel stoves that put properties most at risk. Proper maintenance, care and understanding are the essential tools in protecting the national heritage and people's homes. The National Society of Master Thatchers (NSMT), local fire and rescue services, specialist insurance companies, local authority conservation officers and, increasingly, the chimney lining sector are all working together to reduce the risk of thatch fires. Initiatives include a range of publications, and the NSMT organises public seminars in conjunction with local fire services in areas of the country where there are high numbers of thatched buildings.

The average insurance claim for each serious thatched fire is now close to £250,000. Each fire service call out costs in the region of £40,000 in manpower and resources. While monetary cost is a calculation that cannot be ignored, anyone who has experienced a thatch fire will know that an insurance policy can only reinstate in a material sense. Personal possessions and intimate memorabilia, like heritage, is priceless and irreplaceable. These are the hidden costs in any fire loss claim which cannot be revealed by statistics, and most could be avoided.