Worcester Cathedral Undercroft

Judith Leigh

The crypt of Worcester Cathedral, constructed around the same time as the undercroft (Photo: Chris Guy)

The crypt of Worcester Cathedral is a numinous sacred space, with clusters of creamy stone piers, round arches and white limewashed vaults, little natural light. Under the choir and entered from the south choir aisle, it is the main survivor of the Cathedral – the third on the site – begun by Wulfstan, bishop and later saint, in 1084. It was a monastic settlement, following the Rule of St Benedict, which had been established here by Bishop Oswald, the builder of the second Cathedral in the tenth century, and the successor to a Foundation of 680. A place of worship, learning, hospitality and communal living.

On the south side of the cloister is a more workaday version of the crypt. This is the Undercroft to the former monastic refectory, the monks’ dining hall, also part of Wulfstan’s Norman building of 1084. Reached by the south walk of the cloister on the south side of the Cathedral, this too is a below-ground space, but with just three surviving sturdy squat round piers, a low white-rendered groined vault and slanting southerly light from the highup windows at exterior ground level.

For years the space had been used for random storage. Divided up from time to time to serve passing needs, extensively modified over the years – a survey of the surviving fabric suggests a very chequered history – it had certainly lost its role as a significant contributor to the daily life of the Cathedral. Originally one of its main functions would have been to store provisions for the refectory, the monks’ dining hall above, and the kitchen, a separate building to the west, which no longer survives. Over recent years it had become a blank space in the cloister range and also largely separated from the refectory, now called College Hall and used as a school hall by the King’s School on the other side of College Green.

The aim of rescuing this historic space and returning it to a use fitting the role of the Cathedral in the 21st century and, importantly, in tune with its Benedictine parentage, has developed over a number of years, initiated by the then new dean Peter Atkinson. Initial plans drawn up by the previous architect, Chris Romain, were extensively developed, modified and carried out by his successor Camilla Finlay of Acanthus Clews, surveyor to the fabric of the Cathedral. The project was supported by the National Lottery Heritage Fund, the Friends of the Cathedral and private donors. Work powered on in spite of Covid vicissitudes and the building was finally officially opened, necessarily at low key, as The Undercroft Learning Centre in 2020. This is now a place that can be used by schools, community groups and others for a variety of educational purposes, not least to learn about the history of the Cathedral and its monastic life.

|

|

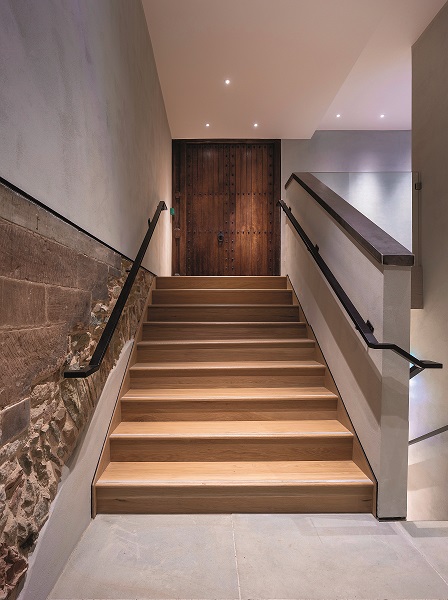

| The new staircase from the undercroft to the cathedral cloister through what was once the entrance to the refectory |

All the work was informed by a thorough understanding of the building and its evolution, based on extensive documentary research and targeted archaeological investigation by Chris Guy, the Cathedral archaeologist. There was a particular need to understand the significance of key parts of the existing structure: the walls now dividing the space, the floor surfaces and levels, and the history of any changes to the vaults. Regarding the walls, it was vital to create a link between the three main compartments to allow the space to function effectively and safely, so the walls had to be carefully assessed to avoid damaging any important historic fabric. Regarding the floor levels, it was possible to identify through archaeological investigation a layer of expendable modern fill below the old broken-up mostly concrete surfaces which enabled a consistent floor level to be achieved throughout. This had the added advantage of allowing more of the moulded pier bases to be revealed and more nearly recovering the original proportions of the space. Regarding the vaults, an area of 19th century alteration to the original medieval fabric was identified, and this bay proved to be the least damaging site for a new staircase and lift to provide the main new entrance incorporating disabled access, foyer, toilets and washrooms. The by-passed old entrance from the east into what is now the seminar space has just been repaired and retained, unused and unaltered.

The guiding principle in recovering this Romanesque space has been to retain as much historic fabric and finish as possible and to complement this with plain clean-lined modern additions and fittings in subdued colours.

The floor throughout is of pale grey Forest of Dean stone. New glass doors providing access between the compartments are set within metal frames, carefully chosen to tone with the masonry. Other doors and modern fittings are in pale oak.Voids in the internal wall surfaces have been filled in with pale brick grilles, lightly limewashed, matching the stonework. Natural light streams in from the high-up windows, strengthened by strip lights and spotlights suspended from the ceiling to provide comfortable working conditions and enhanced by floor lights, especially round the pier bases which delineate these key structural features.

A servery unit in the flexible education space separated from the kitchenette behind by a new brick screen wall

The treatment of the masonry surfaces is a masterclass in itself. In every case what has survived has dictated the conservation treatment. There are bare walls that have been discretely repaired with lime pointing in at least five separate matching mixes. There are walls retaining limewash and walls with lime plaster that have been stabilised with lime repairs. There are vaults with patches of limewash and early lime plaster that have been similarly consolidated. In places the medieval shuttering is identifiable. All this has been carried out with a light touch and sensitive judgment by the main contractors Croft Building and Conservation. Nothing other than soot has been removed or covered up. Different textures abound giving each room a different character and allowing as much as possible of its fabric history to be read.

The new additions have turned the former jumble of historic fabric into a useable space. Entry through a door in the cloister wall at the west end, formerly the entrance to the refectory, now leads to the new stairwell with platform lift and staircase, descending past the vestiges of a medieval vault uncovered during the work and a stretch of ashlar comprising a spectrum of stones including the Old Red Sandstone of the exterior. The new work is all whites, greys, pale woods and steel. At its base are the toilets and washrooms tucked in under the west end of College Hall, which had to be marginally modified, not least to support the organ. The drainage into College Green was a substantial challenge of levels and the resulting archaeological excavation revealed a complex stratigraphy and the remains of former structures still under interpretation, though they are thought to include Saxon and Roman material.

Careful thought had to be given to attaining and retaining optimum environmental conditions in this belowground space. Each room has its own ventilation system and additionally there is a mortar fillet around the base of the walls to aid evaporation. Areas of masonry joints are being left open for a couple of years to aid the drying out. Windows, although at external ground level, have been given frames which can open to allow air from outside to circulate, a feature which has since become more important in times of Covid. Services, including heating, are invisibly laid under the floor slabs, on top of a breathable limecrete floor base. A stainless-steel edge prevents accidental damage to the masonry during cleaning. There is a kitchenette with its own air-handling system with plant and storage space tucked out of sight behind and between the main rooms.

The stone steps on the south side lead from the flexible education space out to College Green, and the new doorway beyond leads into the secondary education space though one of the new openings (Photo: Andy Marshall)

Many visitors to the Learning Centre will be children and there is no doubt that they will experience an entry into another world as they descend the steps and enter this ancient space with its battered history on show. This is largely a ‘conserve as found’ project, as Camilla says ‘ a moment in time’ approach.

![]()

The medieval sculpture of Christ in Majesty on the east wall of College Hall, severely damaged by iconoclasts following the Reformation (Both photos: Andy Marshall)

There was another separate but very significant part of the project. The former refectory above the Undercroft, College Hall, now used as a school hall, retains on its east wall an astonishing sculpture, not widely known but of great art historical significance. It depicts on a huge scale Christ in Majesty seated within a mandorla (or, as it is four-sided, a quadrilobe) surrounded by symbols of the evangelists and set within a decorative rectangular framework of friezes containing now empty crocketed niches. Were it intact it would be one of the wonders of medieval sculpture in the country, but at and after the Reformation it was attacked by iconoclasts and severely damaged. Nevertheless it still displays carving of a very high quality, particularly of the drapery on the figure of Christ.

It is a piece of two periods, the main figure of Christ and the evangelists of the early 13th century, and the surrounding setting of the 14th century. The circumstances of its transformation over these two centuries are still unknown. It was painted and extensive remains of pigment survive, enough to understand the decorative scheme and its development over two main phases. A careful programme of investigation and conservation of this monumental sculpture has been the second part of the project, carried out by Ruth and Torquil McNeilage, and now largely finished. A virtual reconstruction of the original polychrome is being considered.

What remains to be completed is the full interpretation for visitors of both the history of the Undercroft and the Christ in Majesty, particularly in the context of their place in the Benedictine life of the Cathedral, whose principles of teaching, welcoming and caring for visitors continue to be enacted here.

This was not an easy job. Introducing modern services into historic fabric and achieving modern environmental standards is never straightforward, let alone to a building below ground level, of limited size, and furthermore one partly shared with a quite separate institution, the school. And that is before the complications engendered by the Covid pandemic.

Other specialists whose expertise underpinned the project are Andrew Waring the structural engineer, Chris Reading the services engineer and Tobit Curteis whose programme of monitoring enabled an understanding of the challenging environmental conditions. Camilla also wants to acknowledge the collaborative support from Historic England, the Cathedrals Fabric Commission for England and the Fabric Advisory Committee. The outcome is a great tribute to the skills and teamwork of all involved.