Wrought Iron and Conservation

Mild steel and modern arc welding techniques have largely supplanted traditional wrought ironwork. Chris Topp, a blacksmith in the ancient tradition, looks at the historical development of the material and the need for its continued use in conservation work today.

|

||

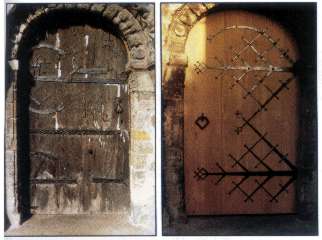

| The 12th century iron bound door of Stillingfleet Church (left) and its replacement made by Chris Topp and Co (right). |

Before the Romans came, Britons were noted for their iron jewellery; an expensive metal in literal terms, for the time and labour expended to make even a small cinder of iron. Early wrought iron was made in the fire from ore and charcoal. The heat was sufficient for the charcoal to reduce the iron oxide to iron, but not to melt it. As a result the silicate slags were included, not refined away as we might do now, but entrained in the fibrous structure of the material. For this reason, the old irons have lasted for hundreds of years. Iron may corrode, but not its coating of silicate slags.

However, little survives because wrought iron may be repeatedly recycled and benefits from reworking. Scrap could be bundled, heated until it glowed white hot, and forged again by hammering into a solid mass to produce an iron of a higher quality.

The earliest surviving architectural ironwork in this country is probably Norman, such as the portcullis, 'ex solido ferro', at Raby Castle and barred treasury windows as at Canterbury Cathedral. Doors too were often strongly bound with iron, frequently of a decorative nature, such as the famous example of Stillingfleet Church, illustrated above. Dating from c1145, it has only recently been renewed. The original is conserved within the security of the church.

From the exquisite precision of the locksmith and the armourer, to the prosaic work of the mender of ploughs and the shoer of horses, the art of the blacksmith developed. Little of this early architectural ironwork is typical. The catch of a door or the bar of a window for example, were more or less ornamented according to the whim of the smith and as today, the available budget. Familiar types emerged, such as the Suffolk latch, and various forms of hinges. Frequently inventive, often crude, but always fashioned in accordance with the nature of the iron.

With the introduction of blast furnaces in the 15th century the availability of wrought iron increased. Craftsmanship reached new heights in the period of Great English Ironwork which started in 1690 or thereabouts with the arrival of a Belgian, Jean Tijou. Some of the finest examples of the period include his own work, such as the screens at Hampton Court, and the work of his disciples such as Thomas Bakewell's garden arbour now known as the 'Birdcage' at Melbourne Hall (1707-1711), William Edney's St. Mary Redcliffe gates (c1710), and the Davies Brothers' gates at Chirk Castle (1715-1721).

The change was toward a freer use of beaten sheet metal ornamentation applied to the bars to form baroque leaf-work, swags, masks and all manner of delights. The techniques were no doubt derived from armoury. The material was superb, not only for its ability to accommodate deep, cold, repoussť work, but also for its persistence, for much of what we can see today has weathered nearly 300 years.

To accurately recreate items from the past, we must, even today use materials and methods similar to those used then. Draughtsmanship is a thing of the modern age, so too are obsessions with dimensions, symmetry and squareness. The delicate lace work of the Golden Gates at Chatsworth is no worse for the absence of a straight line or a square corner. Built without drawings, held together with thousands of tiny rectangular rivets, all different sizes, filed, no doubt, by a team of complaining apprentices. Not easy to restore, but made infinitely more difficult by the attentions of an arc welder of our own time, in the interest of a former standard of 'restoration'.

The iron of this period is now referred to as charcoal iron, a highly carburised form of iron which was made by constant reworking in the fire. It was even hardenable, unlike the puddled irons of the 19th century, and there is no substitute for it. Only very recently has this iron been made again for the conservation industry. It is available in sheet form.

English Ironwork took its course through the 18th century, from Baroque to Rococo, and into a more austere era of mechanisation.

CAST IRON AND THE VICTORIAN AGE

Cast iron has been known to the Chinese since before Christ, and was in general use in Britain in the 16th century, mainly for items like ordnance, firebacks and cooking pots. It was not until the 18th century that any large scale use in architecture became apparent. The Adam brothers experimented with cast iron. At first it was used as an ornament to wrought ironwork. It was not however until after the foundation of the Carron Ironworks in 1759 that the headlong rush into all things of cast iron began, so familiar to us from the 19th century.

Industrialisation enforced new requirements for design, strength and accuracy. The carefree blacksmith became a technician. Ornamental work too became accurate, made to drawings, and characterised by squareness and symmetry. New industrial methods brought mass produced puddled wrought iron, rolled bars of consistent section, and new sections such as angles and tees, as demanded for the construction of the new iron ships.

19th century ironwork was, however, by no means devoid of fun, as can be seen from the railings of the London Law Courts, the Albert Memorial, Holyrood House, and railway ironwork such as Great Malvern station, as well as from the later glories of art nouveau and arts and crafts ironwork.

Wrought iron, with its high tensile strength came again to the fore in the Railway Age. Shipbuilding practices of fabricating structures by rivetting together rolled wrought iron sections, came into use in building, particularly in bridge building for the railways. Riveted plate girders and latticework could span greater distances and carry heavier loads than cast iron structures as tragically illustrated by the collapse of the first Tay bridge in 1878. The wrought iron plate girder became the basic device of building. Assembled into a dynamic framework until, in America, buildings which seemed to scrape the sky became possible.

THE EMERGENCE OF STEEL

With its higher carbon content and greater hardness, the value of steel had been recognised since the earliest days of iron making. But it was slow to produce and expensive. In 1856, in an attempt to mass-produce wrought iron and by-pass the established hand puddling process, Henry Bessemer stumbled upon mild steel, an even stronger, more consistent material. The Bessemer process enabled large batch production, and by 1876 mild steel was cheaper than wrought iron, gradually replacing it for structural purposes. However the material was rather more prone to corrosion, and in cases where durability and resistance to weathering were paramount, wrought iron held its own for nearly another century.

The general fall in standards since the War, and the inexorable process whereby everything must be the cheapest, not only did away with the production of wrought iron, but we very nearly lost the art and skills so important to the working of the material.

CONSERVATION WORK

Over the years technological improvements have made the manufacture and working of ironwork much easier. However for the conservation and replication of old ironwork we should bear in mind that only techniques similar to those extant when the particular piece was originally created will produce a thoroughly accurate replica. If a skill is not exercised it will be forgotten, and with it the ability to create in the manner of the past. The conservation of skills is perhaps just as important as the conservation of the artefacts.

Should the use of modern mild steel in the conservation of wrought iron work be permitted there will also be a tendency to compromise on technique. Mild steel does not for example, lend itself so readily to welding in the fire. Furthermore there is a tendency to use modern, mass-produced sections, which are unlikely to match the imperial dimensions used in the past.

Prior to the 19th century, sections of wrought iron were forged to shape, which gave them a more varied form and surface texture. By comparison restorations in mild steel will appear relatively lifeless and the result will be inconsistent with the texture of the original.

Finally, wrought iron is a material with a proven record of longevity which will prolong the intervals between successive restorations. It is true that its cost is higher but in many cases the cost of the material is small in comparison with the cost of skilled labour, all of which will be lost as the mild steel rusts away.

Wrought iron is currently available for restoration work, primarily through the recycling of old material. Although sources of early charcoal iron are limited, there are vast quantities of 19th century material available from redundant and demolished structures such as bridges, which can be reforged. An increase in demand for wrought iron for conservation work could also make the production of charcoal iron viable. Campaign for Real Iron!