3 0

T H E B U I L D I N G C O N S E R VAT I O N D I R E C T O R Y 2 0 1 4

T W E N T Y F I R S T E D I T I O N

1

PROFESSIONAL SERVICES

Armed with these forward-thinking

documents our practice made an LBC

application for repairs, alterations and an

extension to a small country house in West

Wales. The application had a long and bumpy

ride through the LBC process but through

a series of compromises the application was

eventually approved. We fought very hard over

one particular issue, and while our client was

not overly concerned about the outcome, I was

particularly committed to achieving the result

I felt would benefit the historic integrity of

this particular building. The Grade II* house

in question was built in 1692 and had been

altered in various ways over the centuries. The

front facade of the house was symmetrical

with the original oak cross-mullioned

windows surviving on the first floor, and four

sliding sash windows on the ground floor.

The sash windows appeared to be quite late,

and an investigation revealed they had had

very few coats of paint from new, suggesting

that they were probably 20th century. The

facade also had panels of pargetting that

were unusual for this part of the country.

I felt that the facade had been designed as

a symmetrical and balanced composition,

and the common sash windows detracted

from this composition (see illustrations).

Furthermore, the finest room in the house

was the front ground floor living room,

which has a heavy beamed and plastered

ceiling and ornate plastered overmantel.

From within, the sash windows looked very

weak and were detrimental to the strong

masculine aesthetic of the principal room.

The conservation officer was adamant

that the sash windows were part of the

building’s history and should remain, and his

view was supported by the SPAB. In order

to move the project forward we conceded.

However, while on site we made a second

application for changing the sash windows.

This time we cited Cadw’s newly published

Conservation Principles and particularly its

guidance on understanding heritage values

which takes account of aesthetic value: in

the case of our country house I felt that

aesthetics were a significant consideration.

Cadw also gives guidance on restoration and

states that ‘The restoration of the historic

asset will normally only be acceptable if:

The enhanced heritage value of the elements

that would be restored [the oak windows]

decisively outweighs the value of those

that would be lost [the sash windows].’

The completed facade now has all eight

oak windows either repaired or restored.

The approach taken clearly contravenes

the principle of ‘repair as found’ but it does

recognise the overall contribution made by

the aesthetics of the facade to the building’s

heritage value while ensuring that only the

least significant fabric has been lost.

THE BIGGER PICTURE

When planning works to our built heritage it

is clear that each case needs to be judged on an

individual basis. How far are we prepared to

go to save our historic buildings, particularly

those at severe risk? If you haven’t experienced

‘enabling development’, in whatever form

it takes, you will have heard or read about

it. It clearly has its merits, particularly in a

depressed market where the conservation

deficit destroys any prospect of viability. But

there have been opportunists who have given

this creative form of rescue a bad name and

clearly made many people deeply suspicious

and inclined to question its merits.

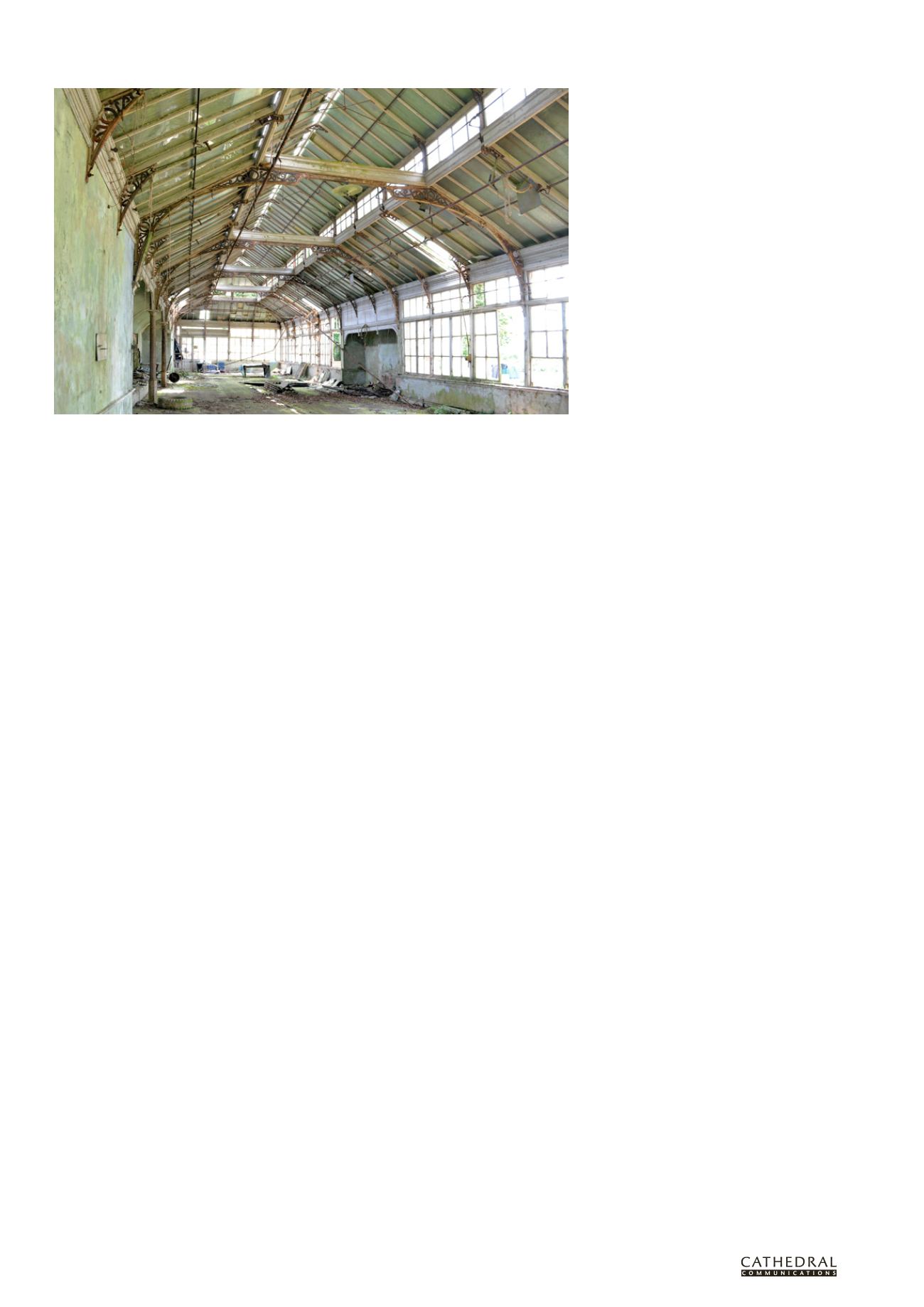

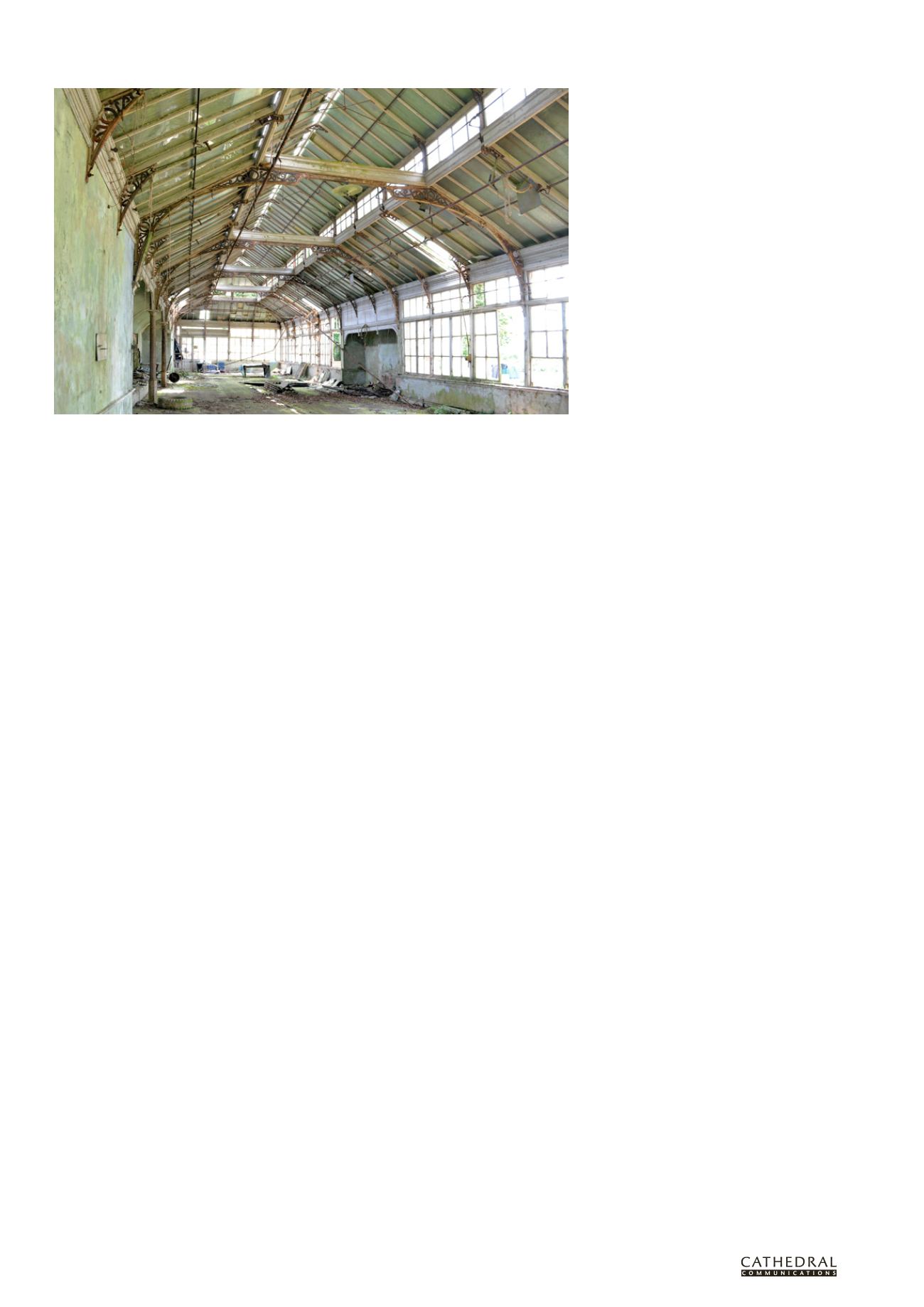

A very large greenhouse adjacent to a

modest country house was built as an indoor

cricket pitch during the 19th century but is in

a very poor and partially collapsed condition

(see illustration). The owner, who inherited

the building, has proposed a creative means

of rescue as the cost of restoration alone is

enormous. However, the local authority will not

entertain conversion of adjacent farm buildings

to fund the restoration. It is difficult to see

how this building can provide a viable and

sustainable restoration plan on its own. Clearly

a covered cricket pitch attached to a small

private dwelling is unlikely to be sustainable,

especially with a £500,000 capital cost. This

project desperately needs the support of the

local authority conservation officer in finding

an imaginative solution if this unusual building

is not to be lost forever, and again a healthy

dose of compromise is required.

It is clear that very little legislation is

black and white and almost always requires

interpretation, but I am sure most would

agree that conservation practice is also not

exact or prescriptive and has many grey

areas. In my experience those who stick

rigidly to the wording of the legislation and

try to interpret guidance literally often lack

confidence in their own understanding.

Greater knowledge and understanding is

the way to better interpretation. It takes

many years of experience to acquire the

tools needed to tackle the challenges

of conservation and compromise.

THE ART OF COMPROMISE

The recession has seen the number of

experienced conservation officers reduced

by a third since 2006, many of whom have

been replaced by planning officers with little

experience of conservation issues. Many

local authorities and public bodies appear

to be struggling in this area, lacking some of

the basic levels of knowledge and expertise.

The private sector is increasingly expected

to provide evidence of expertise through

the accreditation system as a demonstration

that it can provide a ‘safe pair of hands’.

However, the same cannot be said for the

public sector. As the economy improves it

is likely that the construction sector, which

has been restrained for the longest period

in living memory, will bounce back quickly

and I suspect that the public sector will be ill

prepared for such an event.

Recognising significance is one of the

first principles of conservation, but having the

confidence to make big decisions is equally

important, otherwise we will be remembered

as the generation that ‘froze’. It’s perhaps

impossible to take the grey areas out of

conservation, after all, that’s where the fun is;

but there certainly needs to be a tightening

up of understanding and interpretation of

guidance. Most conservation officers work in

isolation in their local authority department,

and that in itself can lead to doubt about some

difficult and grey decision-making. Of course,

each person is different, and the system will

never be perfect, but protecting our heritage

is a high priority which very few contest and

more support for those at the coalface would

be very welcome.

And what of Dan? Well, he still sees Miss Jones

regularly and they have their little disagreements

about points of detail, but over the years they

have both learned the art of compromise, and

the historic environment (at least on Miss Jones’

patch) is much the richer for it.

MICHAEL DAVIES

BSc(Hons) BArch

DipCons(AA) IHBC AABC RIBA is a chartered

conservation, rescuing buildings from ruin,

and designing modern buildings for the

historic environment.

A greenhouse built to house an indoor cricket pitch which is now under threat: enabling development might be

the only way to secure its future