36

BCD SPECIAL REPORT ON

HISTORIC CHURCHES

21ST ANNUAL EDITION

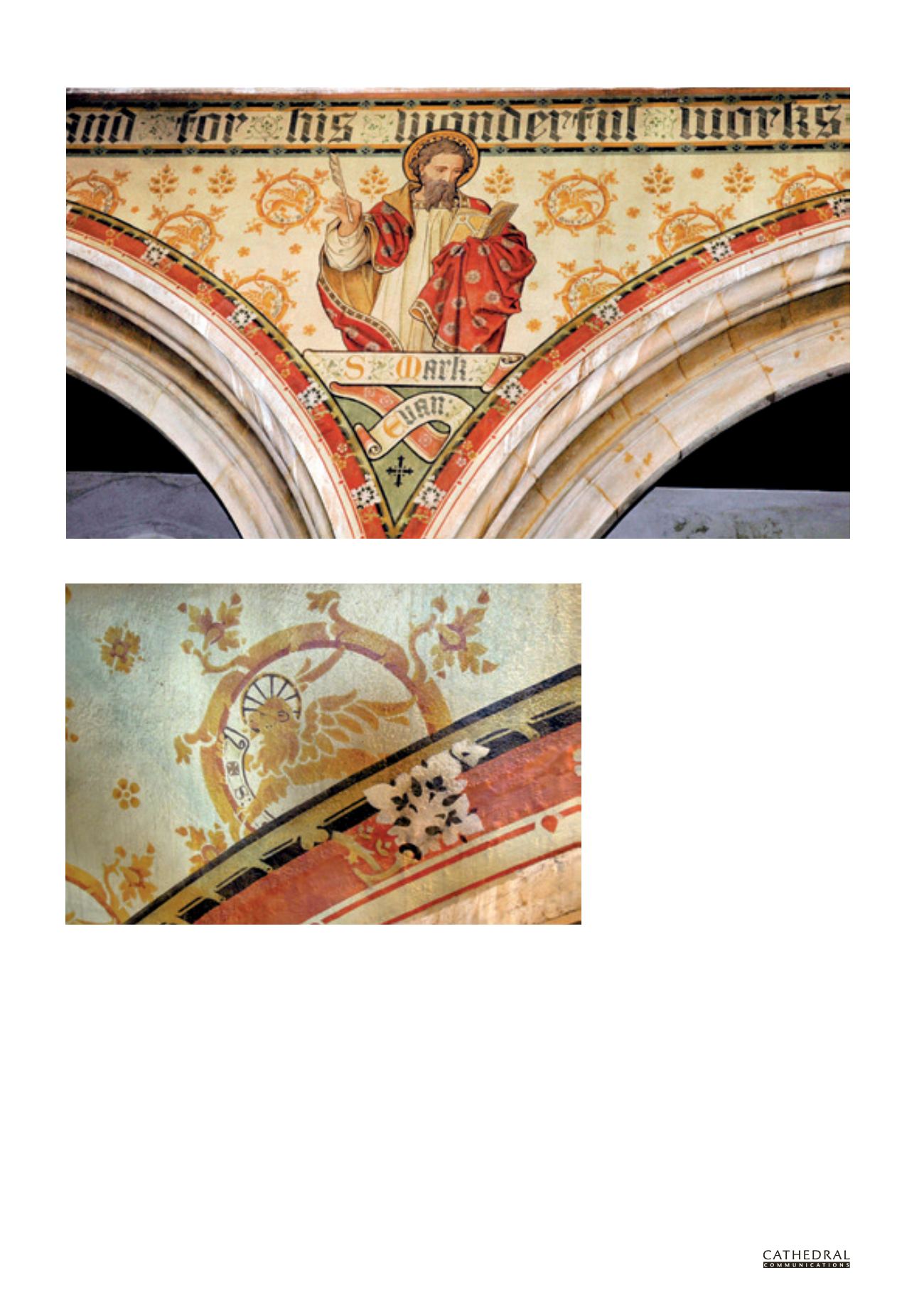

Detail of the Sign of St Mark and a fictive moulding by Clayton & Bell 1908; All Saints, Maidstone, Kent

(Photo: Kevin Howell)

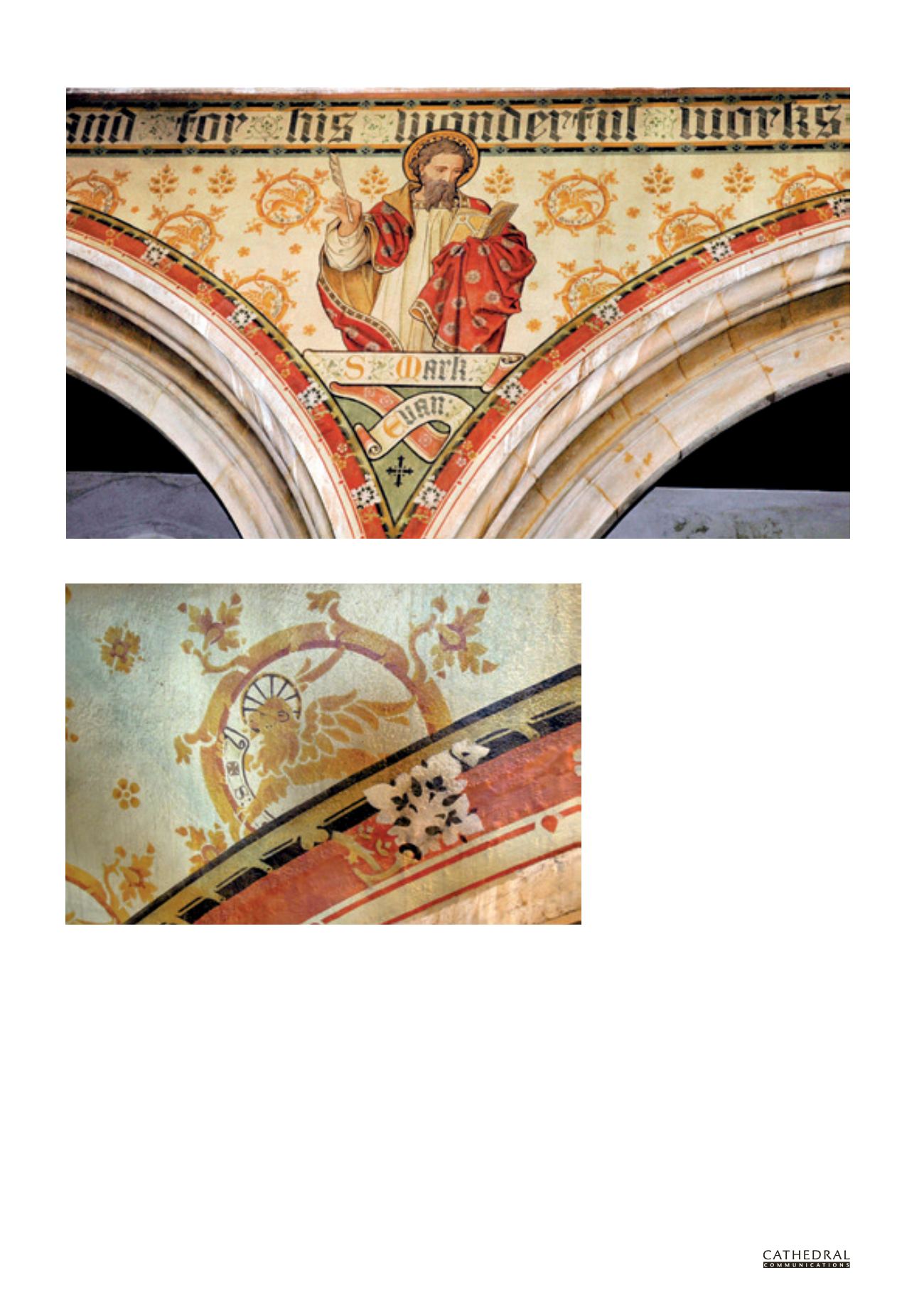

St Mark, one of the Four Evangelists in an impressive late scheme which includes texts, shaded stencils and fictive mouldings; All Saints, Maidstone, Kent, with decorations

by Clayton & Bell 1907–8 (Photo: Kevin Howell)

skilled and artistic to concentrate on other

demanding tasks such as figurative work.

In late 15th-century France the simple

stencilled forerunners of modern playing

cards were introduced, and in Rouen in

the 17th century stencilled sheets of heavy

paper anticipated the development of

wallpaper. However, in England, although

stencilling continued to be used for various

purposes, the really significant catalyst

for its use in the decoration of churches

occurred in the early 19th century with

the burgeoning of the Gothic Revival.

In the vanguard was the brilliant pioneer

architect and designer AWN Pugin, perhaps

best known for his enrichment and decoration

of the rebuilt Palace of Westminster. He also

used painted and stencilled decoration for many

of his other commissions, both ecclesiastical and

secular. Examples include St Chad’s Cathedral,

Birmingham; St Giles’ Church, Cheadle; and the

chapel at Alton Towers, Staffordshire. One of

Pugin’s closest collaborators was John Gregory

Crace,2 whose firm Frederick Crace & Son

carried out much of Pugin’s decorative work.

Pugin published the Glossary of

Ecclesiastical Ornament and Costume in

1844 and Floriated Ornament in 1849, both

containing designs for stencil decoration.

An extract from Clive Wainwright’s

preface to the 1994 reprint of Floriated

Ornament is very informative:

If you read Pugin’s own clearly written

Introduction you will see he argues

that in the middle ages flat pattern was

so successful because the plants were

flattened and arranged in abstract

rather than naturalistic ways.

Pugin himself applied these principles

to stencilling the interiors of his

buildings, also to ceramics, wallpapers,

carpets, curtains, furniture, stained

glass and tiles… Designers from the

1860s like William Morris, Christopher

Dresser and Owen Jones owed a

great debt indeed to Pugin.3

It is this deceptively simple, two-

dimensional quality which gives stencilled

decoration its timeless attraction. Another

significant figure influenced by Pugin was

the architect George Gilbert Scott:

Pugin’s articles [in The Ecclesiologist]

excited me almost to fury, and

I suddenly found myself like a person

awakened from a long feverish dream,

which had rendered him unconscious

of what was going on about him.4

Scott was one of the most prolific architects

this country has ever produced and from the

1840s onwards many young architects and

designers were trained in his office. Some of

the better known among them were George

Frederick Bodley, Alfred Bell, Thomas Garner,

George Gilbert Scott Jr, George Edmund

Street and William White. As their careers

progressed they carried Pugin’s ideas with

them and put them into practice in their

own buildings and decorative schemes.

The 19th-century preoccupation with

architectural style led to the publication of