BCD SPECIAL REPORT ON

HISTORIC CHURCHES

21ST ANNUAL EDITION

37

many scholarly pattern books featuring designs

suitable for stencilling such as Owen Jones’

The Grammar of Ornament published in 1856

and Polychromatic Decoration by W&G Audsley

published in 1882, so there was no shortage

of inspiration for architects and decorators.

Stencilled decoration developed broadly in

tandem with the Gothic Revival and reached its

peak of refinement around the turn of the 20th

century. Depending upon the date and setting,

mural decoration varied from simple ‘stoning

and roses’ – stylised masonry patterns in earthy

reds and ochres – to the most sophisticated

multi-coloured schemes incorporating gilding,

figurative subjects and complex symbolism.

In addition, reredoses, screens, organ pipes

and cases, ceiling panels and roof timbers

were all frequently embellished with stencilled

decoration to emphasise their significance

and disposition in the interior of the church.

In the golden age of Victorian religious

conviction and imperial affluence some

churches may have been completely redecorated

every generation or so as fashions changed

and the existing work began to look shabby.

Sometimes two or even three decorative

schemes lie one on top of the other. However,

by the turn of the 20th century reaction to

this was beginning to develop as may be seen

from the strictures of the noted churchman

and writer Percy Dearmer in The Parson’s

Handbook, first published in 1899:

Stencilling is only an improvement

when used with great reserve and by

an exceptionally competent artist; it

is safer to avoid it… The walls should

be completely whitened, right up

to the glass of the windows, and so

should the tracery and arches...5

After the first world war there was widespread

must have the centre held in place). The skill

is for the bridges to be incorporated as an

integral part of the design. Done well, this

produces naturally elegant patterns and the

bridges go unnoticed. Otherwise a great deal

of time can be spent painting out the gaps

left by the bridges in the stencilled image.

Setting out is the next important step.

For example, to embellish a moulding with

florets, a stencil of perhaps four florets might

be used. The distance from the last floret to

the end of the plate would be the same as that

between the florets, so each time the plate

is moved along the design is self-spacing.

If stencilling a large area of wall, it should

first be marked out with a grid of chalk or pencil

lines to show the position of each repeat of the

pattern. The stencil plate is then fixed in the

first position using pins or tape. The stencil

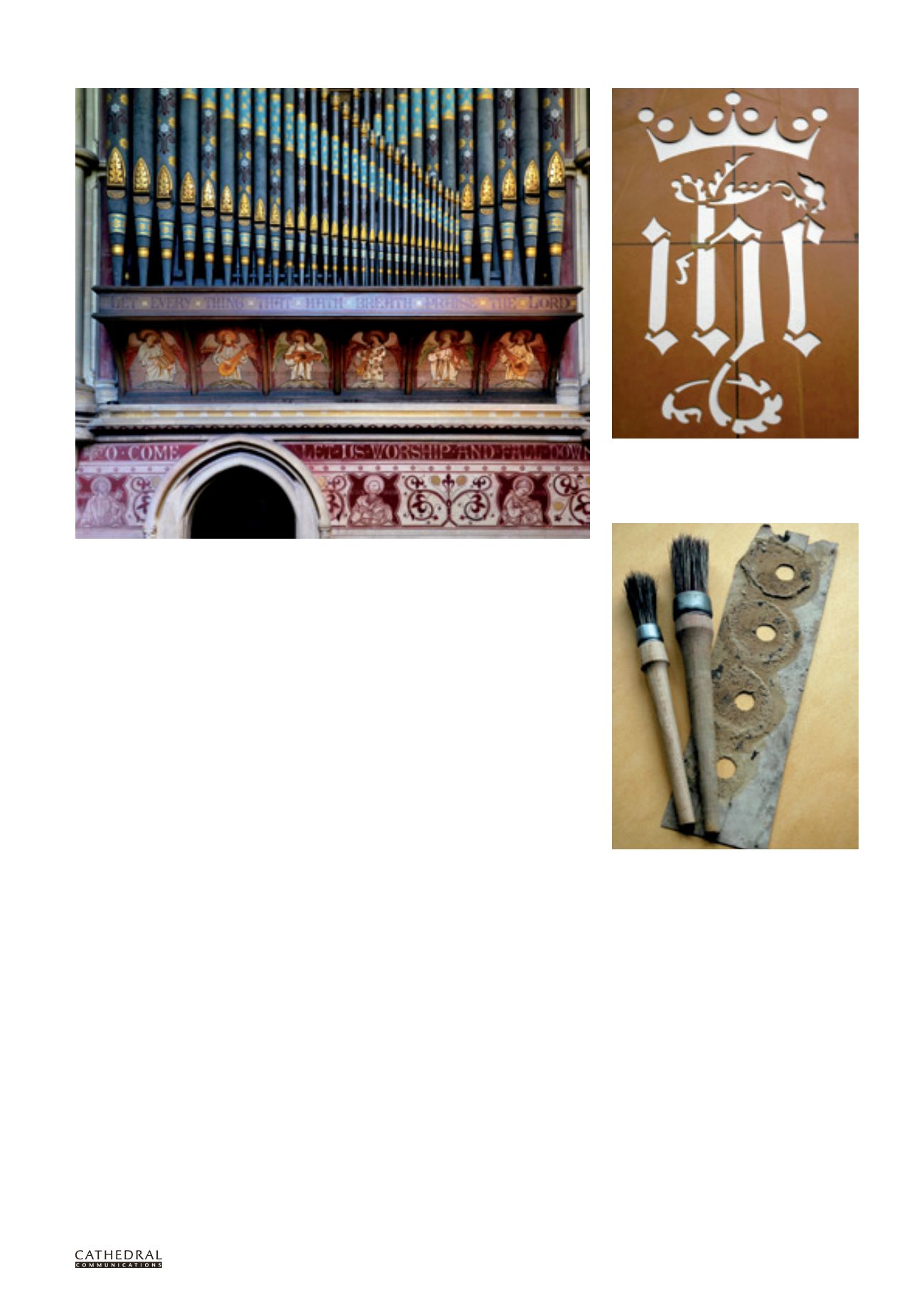

Modern stencil brushes and a Victorian paper stencil.

The paint has built up thickly on the stencil plate

from repeated use. (Photo: Kevin Howell)

IHS stencil used in the restoration of the Lady Chapel,

St Matthew’s Church, Westminster in 1984. The black

lines are used to position the stencil correctly and

the number of bridges to be painted out are kept to a

minimum. (Photo: Kevin Howell)

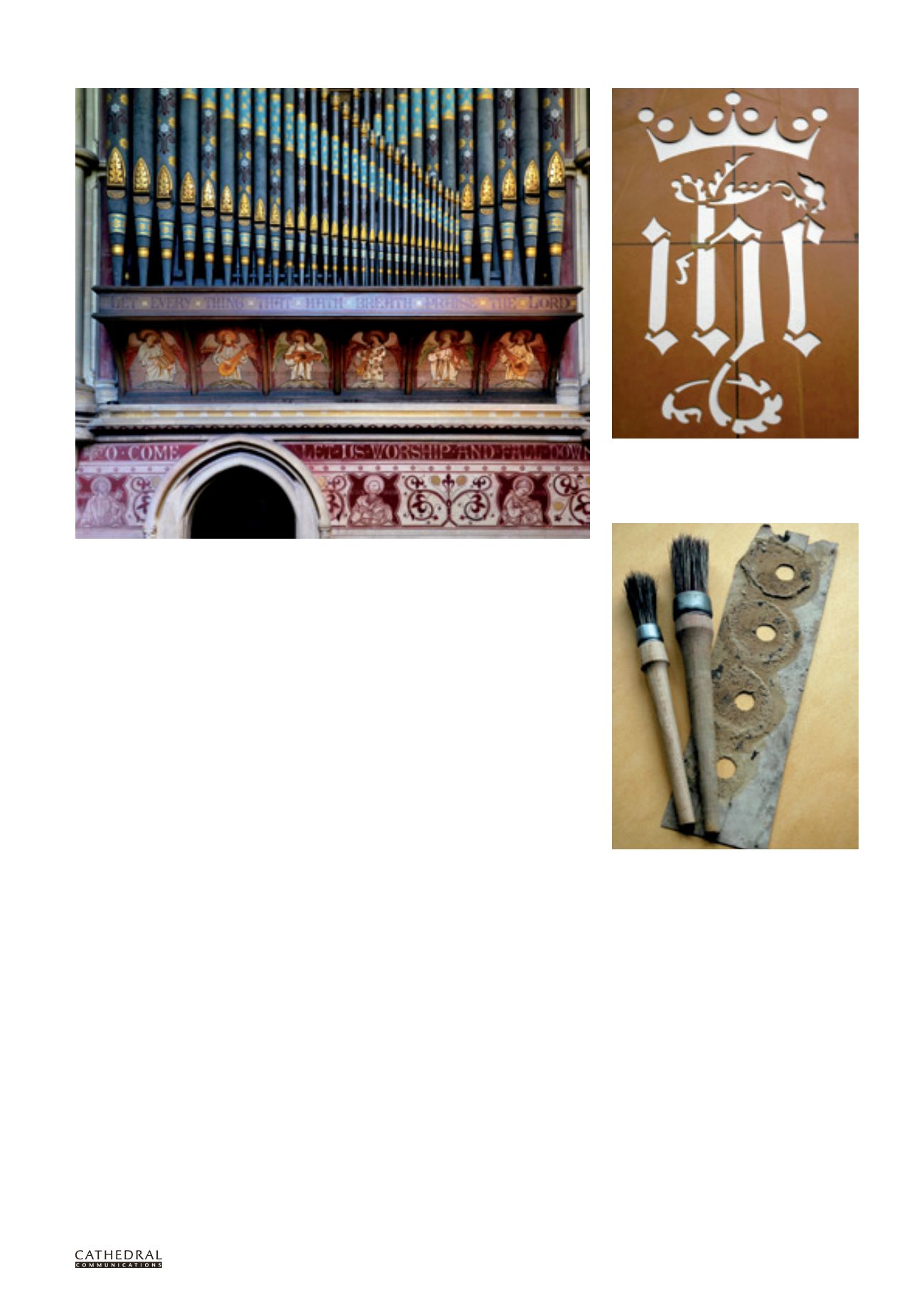

Stencilled and freehand frieze in tempera, with oil-painted organ case above; St John the Evangelist,

Sutton Veny, Wiltshire, by JL Pearson 1866–8, with decorations by Clayton & Bell (Photo: Jonathan Taylor)

disillusionment with the certainties of a

previous age. Gothic architecture in general

was becoming unfashionable and there was

little inclination to spend scarce money on

embellishment. As decorative schemes started

to show their age, increasing numbers were

painted over or removed entirely. Although

the use of stencilled decoration has continued

to this day, the scale and sophistication

achieved at its peak in the late Victorian and

Edwardian eras have never been matched.

TECHNIQUES ANDMATERIALS

Stencilling consists of applying paint to a surface

using a stencil ‘plate’ to create an image, which

can be positive or negative. Many materials have

been used to make stencil plates: sheet lead,

copper, brass, parchment, card, paper, and in

more recent times, plastics. Almost anything can

be used as long it is relatively easy to cut, and

thin and flexible enough to lie in close contact

with the surface, thus preventing the paint from

creeping under the edges. Likewise almost any

paint, dye or stain can be used as long as it is

not too thin, so it does not run under the plate.

For architectural decoration in the 19th

century, card or paper was generally used

for stencil plates. The material was readily

available and cheap, easy to draw on and

to cut. Stencil brushes for applying the

paint were usually round with the bristles

formed into a stubby cylinder shape.

As with most crafts, individuals would

vary their technique to suit the job in hand,

but the general procedure was much the same

as it is today. The design is drawn onto the

stencil plate and cut out with a sharp, pointed

knife. During cutting, ‘bridges’ or ‘ties’ are

left to hold the various parts of the design

together (for example, a letter ‘O’ stencil