1 1 4

T H E B U I L D I N G C O N S E R VAT I O N D I R E C T O R Y 2 0 1 5

T W E N T Y S E C O N D E D I T I O N

3.3

STRUCTURE & FABR I C :

ME TAL ,

WOOD & GLASS

be set into the building’s structure and the

joint between the frame and the wall was

sometimes covered with a timber architrave.

FINISHES

Newly installed oak is paler and more

natural in colour but turns grey as it ages

and weathers. It is highly likely that during

the door’s history it will have had more

than one decorative finish applied. This

might range from an early finish such as

a lime-wash, oil or wax to a 20th-century

paint finish, reflecting changing fashions.

CONSERVATION

To repair and adapt a historic door to

modern circumstances one might apply the

same principles for those developed for a

complete building.

Obviously, doors are subject to more

human attention and wear and tear than other

elements. It is likely therefore that planked

doors, as described above, will have had

several repair regimes since they were first

installed and have their own story to tell about

the history of the building.

It is important, therefore, to gain as

much information as possible about the

doors. By taking a detailed look at them,

carefully examining the way they have been

put together, one may learn more than from

any written account. As with the building as

a whole, the doors are unlikely to be free from

alteration and addition and an assessment

must be made about the relative importance

to the historical narrative of each layer of

intervention. An informed judgement must

be made about which ‘repairs’ have enhanced

their architectural or historical significance

and which have damaged the doors or

detracted from the story.

Early timber doors are very likely to be

part of a listed building, so listed building

consent will be required for any alterations,

and advice should be available from the

relevant conservation officer or the national

heritage body as well as from amenity

societies such as the Ancient Monuments

Society. If the building is scheduled, scheduled

monument consent will also be required for

all conservation work.

At the same time as considering

the intrinsic values of the doors, a clear

understanding of their structural and

constructional integrity must be achieved.

As can be seen from the description above,

the early craft tradition developed to bind

the whole leaf together, and to resist gravity

and the lateral forces of opening and closing

throughout its life. Integrity must be one of

the principal concerns of the repairer.

Understanding how the doors were

originally put together should underpin

the approach to their repair. Measuring

and drawing the door should be reasonably

straightforward, noting evidence of past

changes, and from this the original, current

and possible future configuration of the

various components can be determined.

Once an overall conservation-led

approach has been established, the repair of

the constituent parts can be considered.

nails. Once driven through fillet, plank and

batten they were ‘clinched’ in place (flattened

out on the inner side) with their points buried

in the inner face to tie the timber together.

Nail heads were often left standing proud

on the outer face of the door to add a rich

texture and pattern. As a result, the number

of nails and their arrangement often seem to

go beyond what was needed to bind the door

components together. The pattern might be

articulated with further patterning on the

external face in the form of scribed marks

between the nails.

The heads were often chamfered. In

his 1916 book

, The Development of English

Building Construction

, Charles Innocent

suggests that this form may have been

modelled on the shape of the early wooden

peg fixings (chamfering would have helped to

drive the peg through).

IRONMONGERY

The development of hinges, latches, bolts and

other ironmongery is a subject in its own right

and can only be touched on here. Timber and

metal latches, bolts, stock locks and rim locks

will all be found on early plank doors, and one

of the conservator’s principal investigations

should be to determine which are later

additions and what they may have replaced.

Holes and marks on the timber often provide

evidence of earlier fittings.

Hinges are an integral element in the

construction of doors. Before the introduction

of iron strap hinges, the most common way

of hanging a door was by pivoting it on a hard

vertical post (the harr-tree) which formed

one side of the door, and which was rebated

into sockets (harrs) top and bottom. However,

most surviving early doors have wrought iron

strap hinges. They may have been fixed in the

outer or inner leaf, or both, and they may be

set into the face of the planks and could be

covered by the fillets. Early and vernacular

examples simply had a loop at the hinged end

which is hung on a pintle (an iron hook) set

into the door recess or door frame.

FRAMES

In stone-built medieval houses and in more

humble buildings of later periods, doorways

rarely had timber frames: doors were hung

on pintles driven directly into the stone

rebate. A timber door frame would otherwise

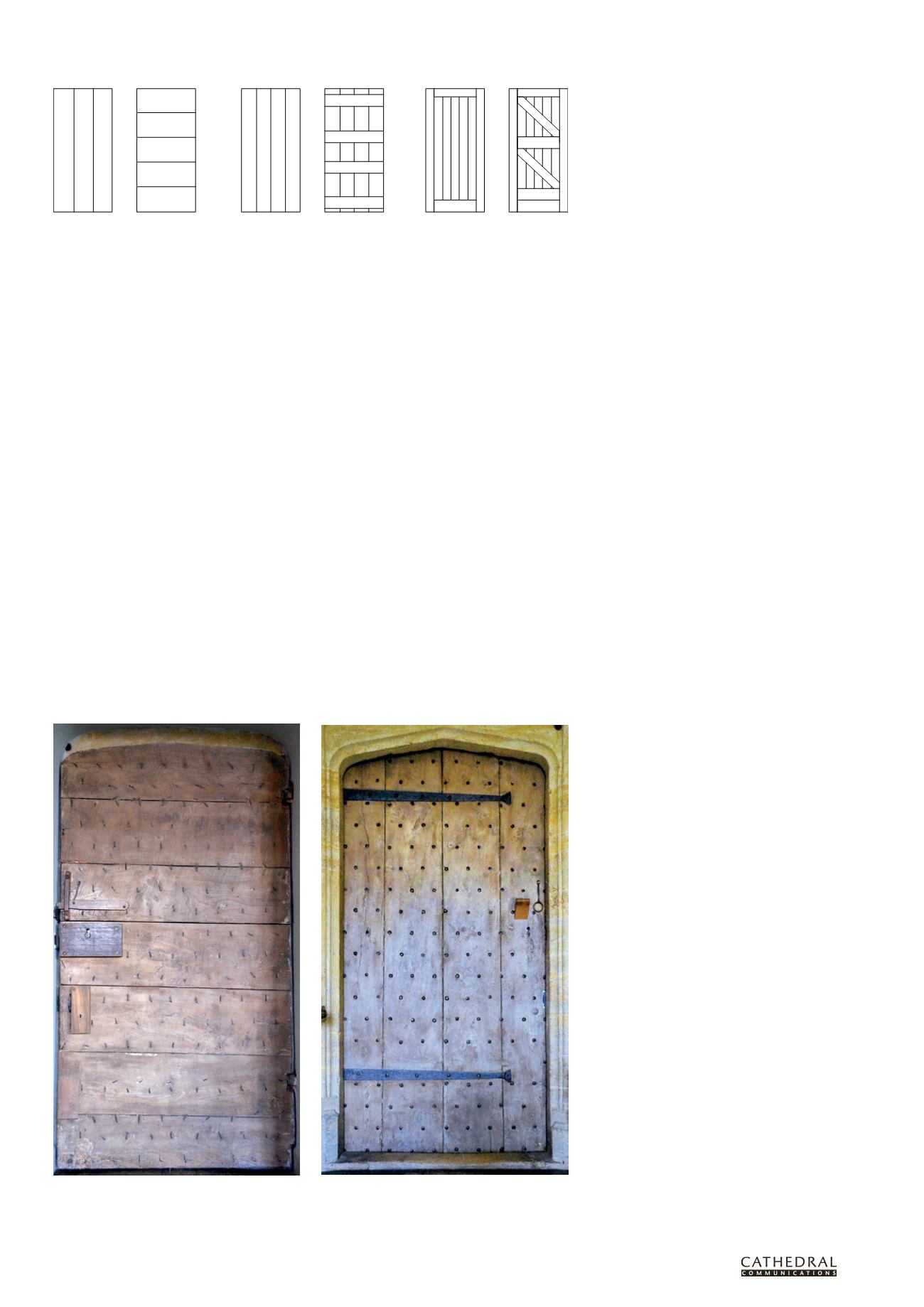

The three principal types of early door (Drawing: Donald Insall Associates)

The two sides of an early double plank interior door at Montacute House, mounted on simple iron pintles

(Photo: Jonathan Taylor, by kind permission of the National Trust)

DOUBLE PLANK

BATTEN AND PLANK

LEDGED AND BRACED

Front

Back

Back

Back

Front

Front