T W E N T Y S E C O N D E D I T I O N

T H E B U I L D I N G C O N S E R VAT I O N D I R E C T O R Y 2 0 1 5

1 3 5

3.4

STRUCTURE & FABR I C :

EXTERNAL WORKS

A variety of refinements occurred

in the late 19th century, such as William

Sugg’s Christina burner of 1874, which

produced a horizontal jet. However, it was the

development of the mantle in 1885 by Carl Auer

von Welsbach which resulted in the greatest

improvement in efficiency. Light was produced

by a non-combustible mantle of mineral fabric

suspended in the flame. The heat caused the

mantle to incandesce, producing more light

than ever. Furthermore, the gas mantle could

be located below the gas outlet. This enabled

curved brackets to emerge from the top of the

cast iron post with the mantle below, directing

light downwards where it was most needed.

Although invented in the early 19th

century, electric arc lamps did not come into

widespread use until the end of the century

when electricity generation became more

common. These produced an extremely harsh

light, far brighter than the incandescent bulb

invented by Edison in 1879, and were ideal for

lighting huge areas, such as factory floors and

streets, but they needed regular maintenance to

replenish their carbon rods. With each increase

in brilliance, lamp posts could grow taller,

casting the light further, and arc lights were

the tallest of the surviving Victorian cast iron

street lamps. As with the gas mantle, the light

source could be suspended from the fitting.

CONSERVATION

Victorian cast iron lamp posts were once

so common that the need for protection

was easily overlooked. As a result, in many

urban areas few now survive. Standing on the

edge of the pavement, the principal threat is

from traffic, including delivery lorries and

refuse-vehicles backing into them. Although

brittle, the cast iron might not break, but

the post could be left leaning at a drunken

angle. Lamp posts may also lean as a result

of ground movement, often caused by broken

drains. Rather than fixing the post in situ, it

is common for local authorities to take the

opportunity to replace the unit with a modern

one which requires less maintenance and is

taller, providing better light coverage over a

far wider area. While this makes the street

safer at night, there is a cost to the character

of the street.

Cast iron lamp posts may also be

removed because they are damaged. Often

this is repairable – some posts include an

inspection hatch at the bottom which is

more vulnerable to damage than the post

itself. Fractures and breakages which do not

affect the structural performance of the post

itself can usually be repaired by specialist

conservation engineers using plating, stitching

or welding. Structural reinforcement may also

be possible if the hollow core is straight and

free from obstruction, allowing a metal tube

to be inserted. This can then be then fixed and

sealed in resin.

Where replacement is unavoidable, many

local authorities still retain old cast iron lamp

posts which could be reused. New castings

can also be made by companies listed in

the metalwork section of this directory (see

page 128), using the surviving components as a

pattern. Modern castings can also use ductile

iron (spheroidal graphite iron) which is less

likely to fracture on impact.

Lanterns are rarely original as they are

easy to replace with a new unit purpose-made

to suit whatever lamp is currently being used.

Sometimes the result is bizarrely incongruous,

with modern light fittings fixed to classical

columns, but several companies supply

reproduction lanterns complete with replica

chimney finials and modern lamp fittings,

including low energy LEDs with an extremely

long service life.

Corrosion can also pose a problem,

particularly at low-level where the post

is exposed to de-icing salts during frosty

periods. Cast iron needs to be protected from

water and from salty water in particular.

Paintwork can be damaged by impact from

bicycles, car doors, signage fixings, and

countless other causes, and small areas

of damage lead to extensive paint loss.

Unfortunately, few councils can afford to paint

lamp posts with sufficient regularity.

In view of competing requirements for

funding and the need to keep streets safe

at night, local authorities are not naturally

inclined to conserve traditional cast iron street

lights unless they are listed, or unless specific

requirements are made in council policy for its

conservation areas.

PROTECTION

Listing varies radically across the UK. A quick

search for ‘lamp post’ in the National Heritage

List for England reveals 400 entries for lamp

posts, 88 of which are in or around Bristol. In

Wales there are 29 list entries of which over

half are in Llandudno. In Scotland, on the

other hand, there are 800 list entries for lamp

standards and holders. Many of our great

Victorian cities have none.

In Bristol the high priority given to the

historic streetscape is due to the tireless

commitment of a community group, the

Clifton and Hotwells Improvement Society.

Initially consulted on a conservation area

appraisal, CHIS developed a system for

recording the different types of lamp post

found locally, enabling a comprehensive audit

of surviving examples in the conservation

area. As a result, their protection was

enshrined in conservation area policy in

2010, and the system has been adopted in

neighbouring Redland. CHIS now works

closely with the local authority to ensure

surviving examples are at least retained in

situ, and salvaged examples in the yard of the

lighting department are being reinstated in key

locations where possible.

While Georgian light fittings are

generally well protected by listing, and are

usually in private ownership, Victorian street

lights remain at risk and their numbers are

dwindling, particularly in England and Wales.

Urgent action is required to secure their future.

Further Information

D Cruikshank and N Burton,

Life in the

Georgian City,

Penguin Group, London 1990

English Heritage,

Practical Building

Conservation: Metals

, Ashgate,

Farnham, 2012

T Fawcett,

Paving, Lighting, Cleansing: Street

improvement and maintenance in 18th-

century Bath

, Building of Bath Museum,

Bath

Clifton and Hotwells Improvement Society

website,

www.cliftonhotwells.org.ukTHE AUTHOR

This article was prepared by

editor Jonathan Taylor with the help of The

Building of Bath Museum, Maggie Shapland

of the Clifton and Hotwells Improvement

Society, Geoff Wallis and Sugg Lighting.

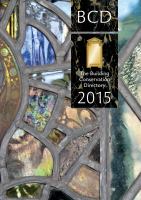

One of several original Victorian lamps still lit by

gas in Canynge Square, Bristol: the lantern was

renewed by Sugg Lighting to a design that has

been in continuous production since 1897, and its

illumination is controlled by photo-cell. The cast iron

post dates from the mid-19th century.

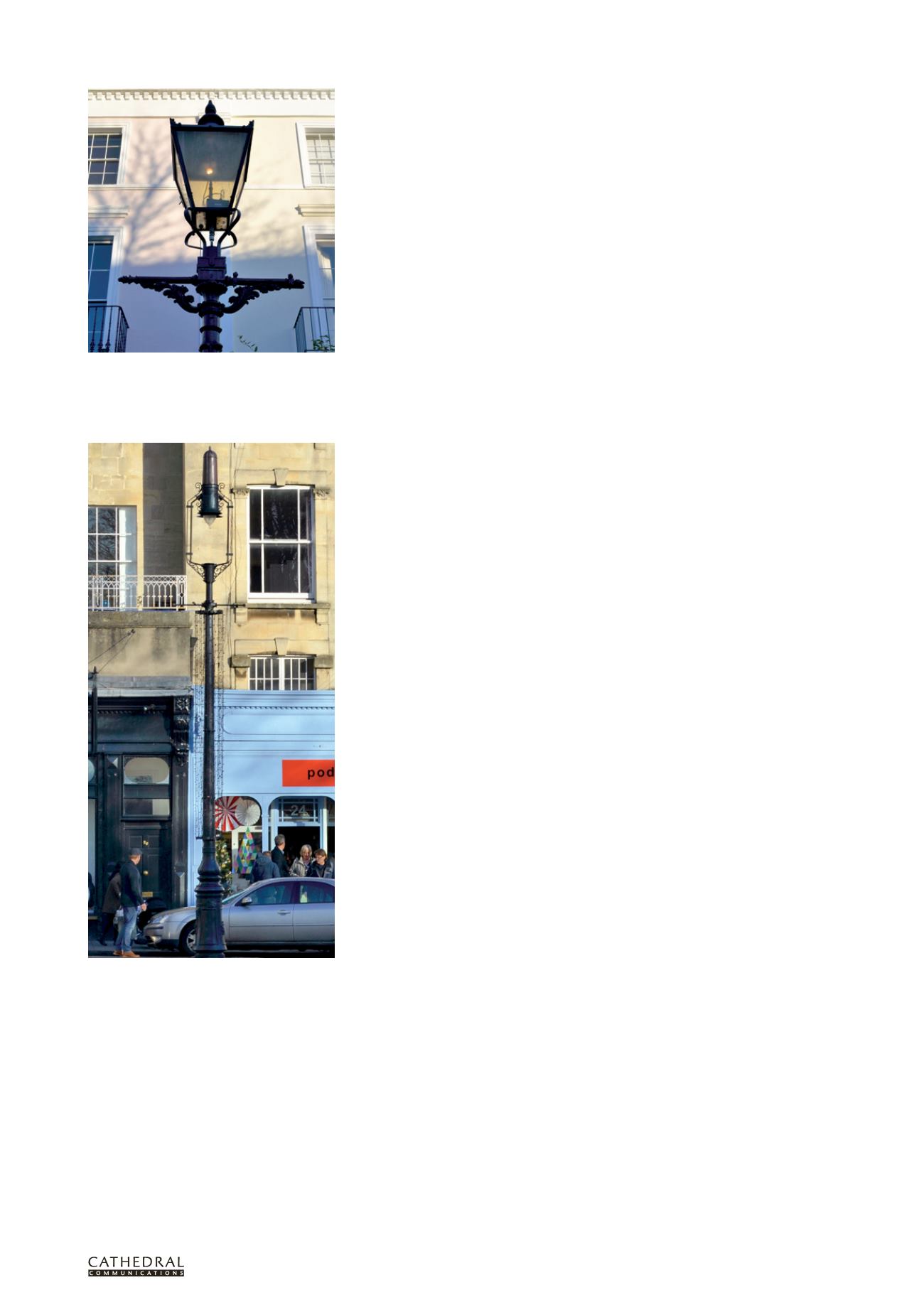

One of two electric arc street lights in the Mall,

Bristol. A public electricity supply was available in

1893 and these lamp posts were installed in 1898.