1 4 0

T H E B U I L D I N G C O N S E R VAT I O N D I R E C T O R Y 2 0 1 5

T W E N T Y S E C O N D E D I T I O N

3.5

STRUCTURE & FABR I C :

GENERAL BU I LD I NG

MATER I ALS

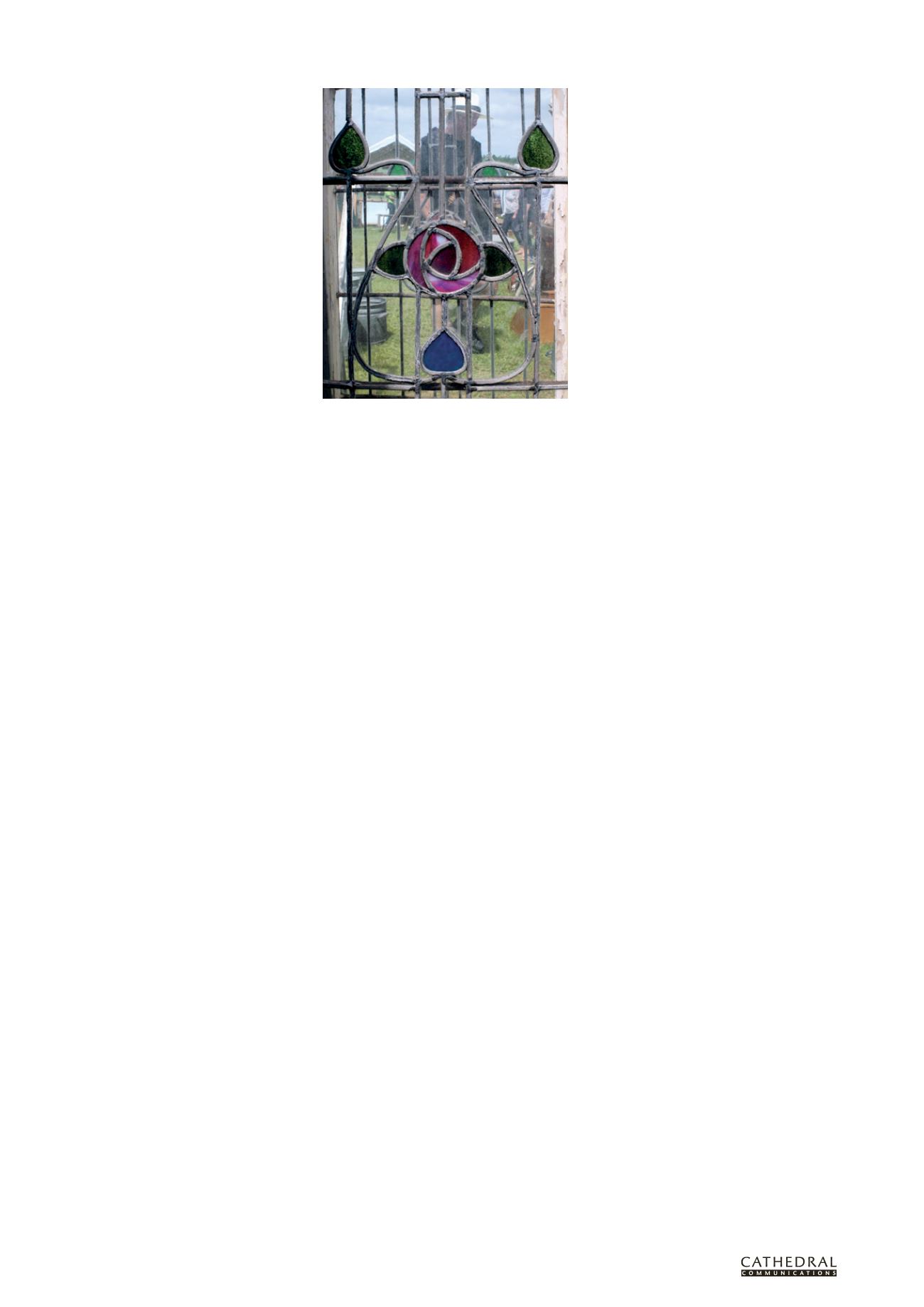

Early 20th-century leaded casement on the stand

of De Zonneroos of Holland at the Salvo Fair 2013,

Knebworth, Hertfordshire (Photo: Thornton Kay/Salvo)

the reuse of salvaged material elsewhere in the

same building.

For example, when the National Trust

recently re-roofed Grade I listed Tyntesfield

House near Bristol, around 1,500 clay tiles

were salvaged from the original roofs and

reused on the most prominent roof slopes,

while new tiles were used elsewhere.

THE NATIONAL TRUST IN NORTH WALES

The National Trust is responsible for one of

the largest collections of historic buildings in

the UK. The trust has made a commitment to

use 20 per cent less energy, halve its fossil fuel

use and generate 50 per cent of the energy it

requires from renewable sources by 2020. It is

also reducing its carbon footprint by making

extensive use of reclaimed materials.

In North Wales this policy has resulted

in a highly successful strategy of recycling

materials needed for the conservation and

repair of buildings across several large estates,

including approximately 80 tenanted farms

and cottages and a number of pay-for-entry

properties and townhouses. Historic materials

are only reused where there is no associated

impact on the significance of the historic

environment. Examples have included:

• thousands of random slates, ridge tiles

and hip tiles, mainly bought from farmers

who were demolishing buildings

• the purchase of complete farm

buildings in the area which had

been condemned for demolition

• the purchase of specific items from salvage

yards, such as cast iron skylights, rainwater

goods, radiators and sanitary ware.

This approach is advocated by BS7913 (2013),

the latest British Standard dealing with the

conservation of historic buildings:

The correct choice of materials for

conservation works is important…

Where possible, existing materials

should be investigated and tested so

that good performance and aesthetic

matches can be achieved. In cases

where the existing material source is not

available, reuse of suitable materials

from salvage might give better results

than newly formed materials.

PROVENANCE

Historic material belongs to a dwindling

resource that we should be safeguarding for

future generations. Where there are plans to

use architectural salvage, the first step should

be to source materials responsibly.

Heritage crime, especially the theft of

valuable components for resale, continues to be

a serious problem in the UK. While lead theft

(on the increase again at the time of writing)

tends to dominate media coverage of heritage

crime, other materials, especially building

stone, are increasingly being targeted. Cases

of large-scale stone theft have been steadily

rising over the past two years, with a focus on

areas rich in high-value building stone such as

Yorkstone, Kentish Rag and Cotswold stone.

Curtilage walls such as those around

churchyards are especially vulnerable.

While security measures may be focussed

on protecting lead roofs or valuable artefacts

inside the building, cemetery walls are often

directly accessible from the road, allowing

irreplaceable historic stone to be stripped

and loaded straight onto a flatbed lorry. In

October 2013, for example, 500 coping stones

were stolen from a perimeter wall of Earnley

Parish Church in West Sussex. The following

month 40m2 of historic Yorkstone paving

valued at £7,000 was stolen from central

Rochester by thieves posing as workmen and

using stolen highways barriers to make the

work look legitimate.

If you have any doubts about the

provenance of an item, check the theft alerts on

Salvoweb

(www.salvo.co.uk), where hundreds

of stolen items are listed. If doubts persist it is

best simply to walk away and, if there is reason

to believe the item is stolen, use the 101 non-

emergency police number to report it.

Salvoweb also includes a list of dealers

who have signed up to the Salvo Code. There

is no legal regulation of the architectural

salvage trade but the code, established in 1995,

has encouraged many businesses to take up

voluntary self-regulation. Signatory businesses

undertake to make every effort to ensure

that items which they buy have not been

stolen or removed from protected historic

buildings without permission. Using traders

who have signed up to the code demonstrates

support not only for ethical traders but also

for the principle of regulation itself, hopefully

encouraging other businesses to follow suit.

Historically, there has been a degree of

mutual distrust between the architectural

salvage trade and conservation professionals.

Some in the salvage trade feel it has been

portrayed unfavourably despite the fact that

many of those involved, especially among the

more long-standing operations, are passionate

both about saving historic craftsmanship from

the skip and about the environmental benefits

of reclamation.

Clearly, renewed efforts are necessary to

build and extend cooperation between the

conservation and salvage camps. In 2013 a

report ‘Heritage and Cultural Property Crime

National Policing Strategic Assessment’

was published by the Association of Chief

Police Officers. Its conclusion includes the

recommendation: ‘Improve the relationship

with traders, second hand dealers, salvage

firms and auctioneers in order to improve

the flow of intelligence’. It remains unclear,

however, how far the recommendation has

progressed towards reality.

The stakes are high, both in terms of

curtailing crime and promoting a healthy

salvage sector. Surveys of UK salvage

businesses by Salvo in 1998 and 2007 showed

a large increase in the value of sales but a

general decrease in the volumes of materials

salvaged as the trade shifted its focus, selling

more new and reproduction alternatives.

USE IT OR LOSE IT

In the 2009 edition of

The Building

Conservation Directory

SPAB-trained

architect Mark Hines made a persuasive

and impassioned call for the reuse and

environmental upgrading of the UK’s vast

stock of unlisted Victorian and Edwardian

terraced housing. Hines’ argument was in

part a response to the destruction wrought

by the Pathfinder Programme which,

according to SAVE Britain’s Heritage,

saw the demolition of some 16,000 homes

which could have been refurbished.

Pathfinder saw the costly and often

unpopular destruction of an increasingly scarce

resource – affordable, well-built housing.

Perhaps it is now time to reconsider the fate of

the associated resource of historic materials

and components removed during demolition

or refurbishment. That they have been cast

adrift from their original contexts needn’t

render them worthless either as heritage or

as objects with useful life left in them.

Well-established conservation principles

such as maximum retention and the honesty

of modern interventions are integral to the

practical – as opposed to the legal – protection

of historic buildings. These principles, however,

may be inappropriate in the context of legally

unprotected traditional buildings where

more radical and imaginative interventions

may be needed to improve functionality and

compatibility with modern lifestyles.

Recommended Reading

R Ellis, ‘Security and Historic Buildings’,

The Building Conservation Directory

,

Cathedral Communications, Tisbury, 2011

J Fidler, ‘Architectural Salvage: Right or Wrong’,

Context

, 24, The Association of Conservation

Officers (now the IHBC), Guildford, 1989

L Grove and S Thomas (eds),

Heritage Crime:

Progress, Prospects and Prevention

,

Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke, 2014

Acknowledgements

This article was prepared with the assistance

of Mark Harrison (English Heritage),

Thornton Kay (Salvo), Rory Cullen, Elizabeth

Green and Emyr Hall (National Trust).

DAVID BOULTING

PhD is the deputy editor

of

The Building Conservation Directory

and

joint editor of

Historic Churches

. He is a

former teacher and university lecturer.