1 4 4

T H E B U I L D I N G C O N S E R VAT I O N D I R E C T O R Y 2 0 1 5

T W E N T Y S E C O N D E D I T I O N

SERV I CES & TREATMENT :

PROTEC T I ON & REMED I AL TREATMENT

4.1

LINSEED OIL PAINTS AND MASTICS

Applications and limitations

PETER KACZMAR

A

T THE

start of the last century wood-

coating technology enjoyed a period of

relative stability when little energy was

expended on developing new or improved

coatings. Then, joinery was manufactured

from large-sectioned, slow-grown wood and

protected with flexible lead-based paints

which seldom showed the types of failure

that have become so characteristic of their

modern equivalents.

Based on the frequency of observed

failures, one could be forgiven for saying

that today’s coating technology seems to

have taken a step backward. This apparent

decline in the performance of wood coatings

is often blamed on shifts in attitudes in

silviculture as timber made the transition

from abundant building commodity to scarce

and valuable resource. The consequence was

that the definitions of acceptable timber

quality were redefined to maximise the

use of a shrinking resource. This in turn

placed seemingly unrealistic demands on

existing coatings, which were expected

to perform well despite the fact that the

nature of the substrate had changed.

This is reflected in our historic buildings,

where the original woodwork was generally

manufactured from large-sectioned,

slow-grown, and hence stable, temperate

hardwoods which do not exert the same

demands on paint coatings as today’s more

rapidly grown counterparts.

In reality, this is an oversimplification

because it does not take into account

legislative pressures against the use of lead

paints, which began as early as 1921 when

the International Labour Organisation, in

recognition of the toxicity of these products,

implemented a convention restricting the

use of white lead (basic lead carbonate) in

paints. These concerns culminated in the

establishment of environmental legislation

implemented by the European Commission

REACH (registration, evaluation,

authorisation and restriction of chemical

substances) regulations in 2006. The REACH

regulations allow the manufacture and use

of white-lead paint only under licence in

controlled and special circumstances for

the repair and restoration of Grade I and

II* listed historic buildings (Category A B

and C(S) in Scotland) to enable the use of

authentic finishes. Strict regulations apply

to its use and the general sale of lead paint in

the UK is prohibited.

LEAD-FREE PAINTS

Against this backdrop, the wood coatings

industry was forced to adapt and

manufacturers responded by developing new

types of coating, including some systems in

which the lead component (lead carbonate)

was substituted with titanium dioxide as the

alternative pigment.

One of the main advantages of lead

carbonate is that it reacts with linseed oil

to produce fatty acid soaps which are tough

and elastic and also have good wetting

properties. This is arguably the principal

reason why white lead was so widely used for

the protection of wood substrates: it could

produce a resilient, relatively impermeable

protective film capable of responding to

in-service movements of the wood caused

by changes in air humidity and substrate

moisture content.

The inherent ability of the old lead-based

paints to accommodate movement in the

substrate was the key to their success when

used to protect exterior wood. Formulation

technology has responded to restrictions

in their use by developing alternative

formulations, among them the acrylic and

vinyl-based systems and polyester products

which led to the development of ‘traditional’

alkyd systems.

THE RISE OF ‘COMPLIANT COATINGS’

In many ways history is now repeating itself:

in just the same way as health and safety

controls signalled a radical change in the

direction of developments during the 20th

century, the imposition of environmental

legislation set into motion further changes

at the start of the 21st. The recent changes

stem from two European directives on

volatile organic compounds (VOCs). The

first, the Solvent Emission Directive (SED)

1999/13/EC, has been fully implemented

since 2007 and places limits on installation

or plant facilities according to total

annual VOC emissions. The second, the

Paints Directive (PD/DECO) 2004/42/EC,

applies to coatings for use on buildings,

their fittings and associated structures as

well as products for vehicle refinishing. It

divides the coatings into 12 subcategories

and sets VOC limits for each one.

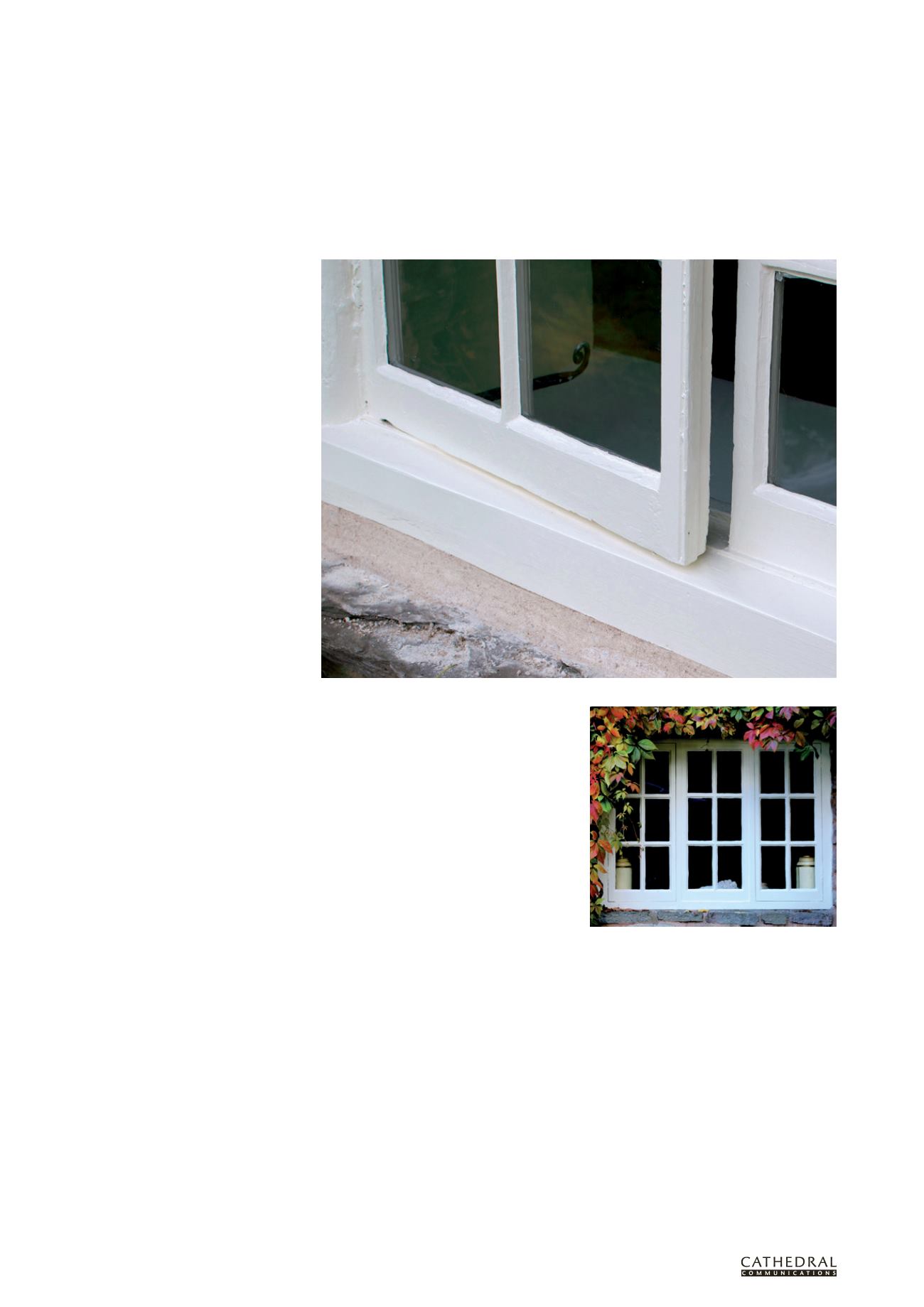

These directives have promoted the

A timber casement window painted with a linseed oil paint (Photo: Matthew Evans, Welsh Heritage Décor)