T W E N T Y S E C O N D E D I T I O N

T H E B U I L D I N G C O N S E R VAT I O N D I R E C T O R Y 2 0 1 5

1 5 3

SERV I CES & TREATMENT :

PROTEC T I ON & REMED I AL TREATMENT

4.1

quarried and reclaimed stone is unavailable,

the replacement should be the nearest possible

match, both geologically and visually.

Understanding of the nature of

the building stone and its weathering

characteristics is fundamental. The range

of building stone types used historically

across the UK is wide, and properties vary

considerably even within a geological group.

For instance among the English Jurassic

(oolitic) limestones, which include the Bath and

Portland groups, there is considerable variation

in weathering characteristics and durability.

Best masonry practice dictates that the

natural geological bedding planes of the stone

should be observed and stones laid with the

correct orientation of the bedding planes,

relative to their location in the building. For

example, ashlar facing stones in a flat wall

face should be laid with their natural bedding

planes parallel with the ground, not face

bedded, while blocks used for projections

(cornices, any element with a vulnerable

soffit) should be laid with their bedding

planes vertical and at right angles to the

building face to avoid the risk of delamination

of layers. Failure to understand the natural

features and weathering of building stone,

the gradual erosion of surfaces that occurs

naturally versus the accelerated deterioration

that results from masonry defects, can result

in flawed condition assessment and incorrect

specification of repair work. It may also lead to

the loss of historic fabric if masonry is wrongly

condemned for replacement rather than repair.

TRADITIONAL MASONRY DETAIL

AND PROTECTION AGAINST

RAINWATER PENETRATION

Allied to the understanding of building

stone, is knowledge of traditional masonry

construction, which is also fundamental.

Survey should include the study of original

detail, how masonry blocks were worked and

dressed, how joints were finished (and their

original width), and whether the masonry is

functioning correctly. Defects and failure of

the joints must be identified as joint treatment

is an integral part of masonry repair work.

Stone decay at the arrises of open, eroded

joints is a very common defect, especially

on projecting elements such as cornices and

mouldings, and compromises the integrity

of masonry and its ability to shed rainwater.

Traditional saddle joints were designed to

direct rainwater falling on cornices away

from the perpend joints, with the stone profile

raised at the joint shoulders. On deep and

large cornices, decayed, open joints promote

deterioration of the soffit, so grouting and

repointing is essential. Particular attention

should be paid to all protective masonry

details that shed rainwater. These include

the drips (located on the lower leading edges

of cornices and other projecting mouldings)

and falls (sloping surfaces) on copings and

cornices. Where these details are decayed or

damaged, any water-traps which form will lead

to stone decay, and it is essential to reinstate

their weathering function.

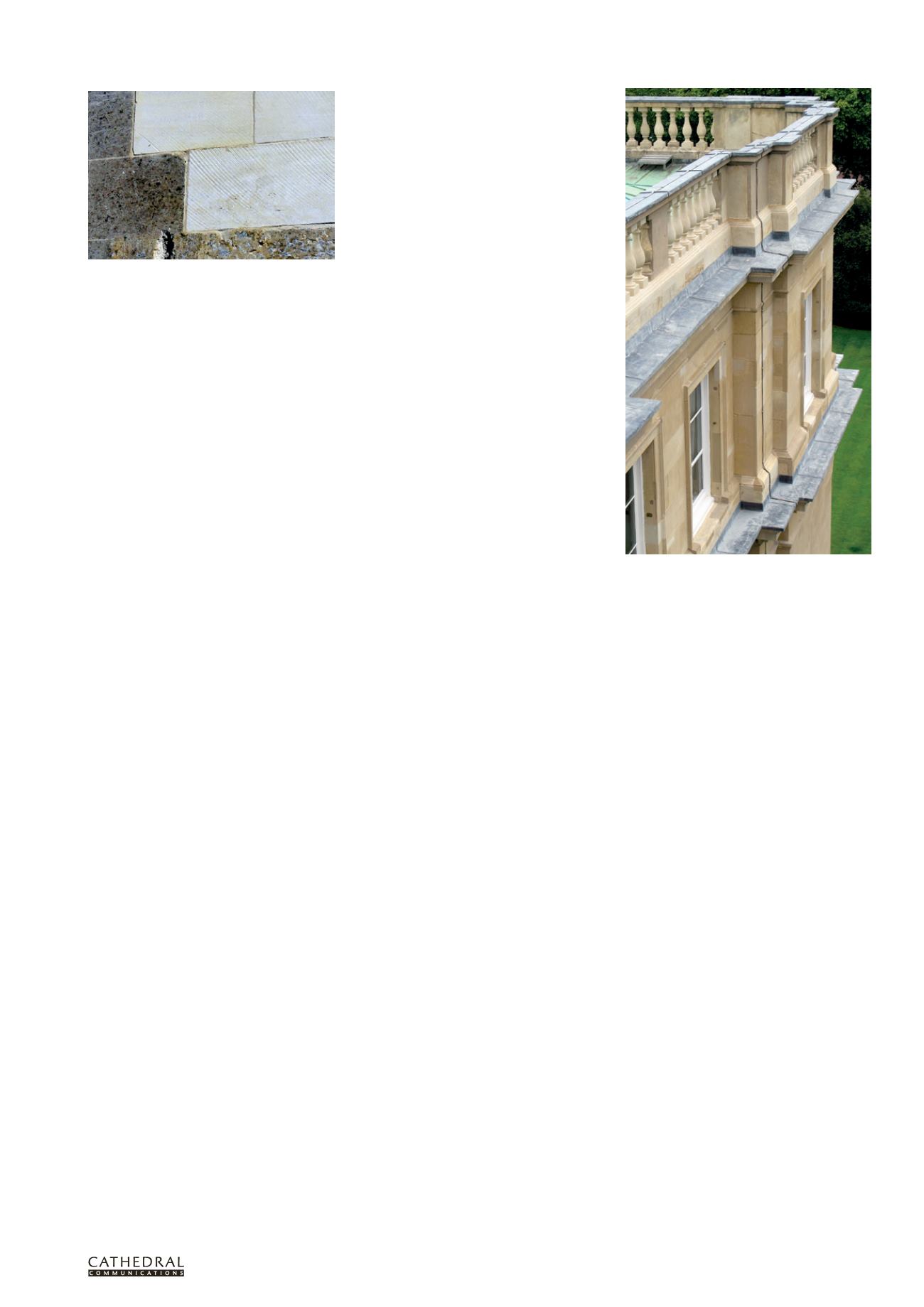

In some cases the installation of lead

protection may be an option. Lead sheet

weatherings have been extensively used

historically to protect cornices, pediments,

copings and other exposed details from

weather. They can prolong the life of

stonemasonry if properly detailed, with

welted joints and a drip to throw rainwater

(in accordance with Lead Sheet Association

guidance) and may offer an alternative to

extensive stone replacement. The installation

of leadwork involves cutting a chase into the

masonry above to fit a cover flashing, and this

will need to be weighed against the potential

benefit of protection that lead can provide. In

addition, weatherings will inevitably have some

impact on the appearance of the building (see

illustration), although this may be relatively

minor when seen from ground.

Cracks

Visible defects commonly include cracks

and fractures which may range in scale from

hairline to 10mm or more. It is important

to determine the cause of fractures and

whether they relate to hidden elements such

as imbedded ferrous metal fixings, or to

structural movement. Dog cramps were widely

used in historic masonry to provide additional

lateral restraint where necessary. They were

often placed relatively near the stone face and

when corrosion occurs the expansion of rust

leads to characteristic fractures and spalls

occur, normally at the upper corners of the

affected blocks. The use of non-destructive

testing methods like metal detection can

be helpful to locate concealed cramps and

reinforcement of historic repairs. Gentle

tapping (‘sounding’) with a small metal tool

helps to detect detachment where there are

visible spalls, fractures or other defects.

Old cement repairs

Past repairs, as well as visible stonemasonry

defects, should be checked. Unfortunately,

many historic buildings exhibit a legacy of

historic repair work in unsuitable materials,

often in excessively hard and impermeable

mortars such as the ubiquitous ordinary

Portland cement (OPC). In the worst cases

large areas of masonry were refaced with

OPC mortars. Commonly used in the past,

as an inexpensive and easy repair option,

this practice unfortunately still occurs, often

without regard to original joint lines and

other historic features. This kind of repair

exacerbates the decay of more porous and

permeable underlying stone, and failure

eventually occurs at the interface between

the two. Such large scale re-facing of stones

should never be considered a repair solution or

alternative to correctly detailed stonemasonry

repairs (indents, replacement units) based

on traditional masonry skills. Unfortunately,

however, past repairs of this kind, from small

to large scale, are often so extensive that the

best that can be practically achieved is to

renew those that have failed and detached, and

are evidently causing problems, and leave those

that remain well bonded, provided they are not

posing a health and safety risk.

PRINCIPLES AND PRACTICE –

REPAIR OPTIONS, CRITERIA FOR USE

& OTHER ISSUES

One principal aim of remedial work is to effect

repairs with minimal loss and alteration of

historic fabric. Maintaining the integrity of

masonry and restoring essential detail, such

as weatherings, where damage or loss has

occurred are also key objectives. In practice,

replacement may be the best option if the

structural stability or weathering function of

individual stones is completely compromised

and cannot be restored with localised surface

repair. However, isolated and discrete defects

on a block, such as a spall from a corroding

ferrous cramp or decay adjacent to an open

joint, can often be repaired using stone indent

repairs whereby a new stone is cut and shaped

to fit the damaged area.

For sheltered or relatively small areas lime

mortar repairs may be used. A range of lime

Lead has been used extensively on this Grade I listed

building to protect vulnerable historic masonry, such

as the Bath stone copings and cornices. Leadwork

which has been properly detailed in accordance

with the guidance of the Lead Sheet Association

can prolong the life of stonemasonry, in some cases

providing an alternative to extensive repair or

replacement work.

Finish is important: these clean new replacement

stone facings jar with the original masonry and

mechanical saw marks disfigure their surface.