T W E N T Y S E C O N D E D I T I O N

T H E B U I L D I N G C O N S E R VAT I O N D I R E C T O R Y 2 0 1 5

3 5

1

PROFESS IONAL SERV I CES

Local listed building consent orders may

be issued pro-actively by the local planning

authority, and are likely to be of most

use covering groups of similar or related

buildings in multiple ownership, where

predictable, routinely consented works are

commonly carried out across the group. They

have the potential to establish consistent

approaches to issues of maintenance, repair

or minor alteration, to increase certainty

over the aspirations and requirements of

all parties, and to save time and resources

for owners and local planning authorities

alike. They may also be more ambitious in

scope, driving other changes, such as the

regeneration of Little Germany, Bradford

(see Case Study 2 on this page).

CASE STUDY 1

The University of Sussex

Sir Basil Spence’s University of Sussex was the

first of the new wave of UK universities founded

in the 1960s, receiving its Royal Charter in

August 1961. Sitting in semi-rural downland

it includes a library, lecture rooms for arts

and sciences, a non-denominational place of

worship, an arts centre and Falmer House, the

university’s social centre. All are articulated

in red brick and concrete with hollow vaults,

concrete beams, arches and fins.

These original university buildings which

make up the heart of the campus, were given

listed building status in 1993. In total there are

eight listed buildings on campus, one at Grade

I and the other seven at Grade II*. Falmer

House is one of only two educational buildings

in the UK to be Grade I listed in recognition of

its exceptional interest.

Proposals for a listed building heritage

partnership agreement covering the eight

Grade I and Grade II* listed buildings at the

University of Sussex are progressing well.

Developing out of 20 years’ experience with

management guidelines which converted

easily into a non-statutory HPA, the LBHPA

is a natural progression which will give the

university greater certainty and flexibility in

the management of its buildings.

Like the management guidelines that

preceded them, the LBHPA is relatively brief

and workmanlike. It is divided into two

parts, with several annexes. The first lists the

parties to it, and gives a brief statement of

significance, followed by the works consented

under the agreement and the certificates of

lawful proposed works which it also details.

Part 2 gives the terms of the LBHPA, its

period – currently proposed as ten years with

reviews in the fourth and ninth years – and

the basis of the agreement (including review

and modification, records and revocation).

Part 1 of the agreement also categorises the

work:

• Type 1 works, which are

de minimis

(minor works such as cleaning or

routine maintenance) and would

not usually require LBC (and are

therefore not the subject of certificates

of lawful proposed works)

• Type 2A works, which have been

granted listed building consent

under the terms of the LBHPA

• Type 2B works, which are subject to

certificates of lawfulness of proposed works

• Type 3 works, which need LBC but which

do not currently fall within this LBHPA

• Emergency works, which may be

carried out outside the LBHPA, subject

to a list of those undertaken being

submitted annually to the partners.

The partners to the LBHPA have long worked

relatively flexibly and there is no intention

to try to cover all possible eventualities in

the LBHPA, especially as experience has

shown that buildings and spaces can pass

out of use relatively quickly. The chemistry

laboratories which Spence designed, for

example, are now almost totally redundant,

while the university’s overriding need is now

for computer rooms. The watchwords for the

LBHPA are therefore partnership, brevity

and flexibility. With these, certainty and a

reduction in unnecessary process should

continue to be possible.

CASE STUDY 2

Little Germany, Bradford

English Heritage and Bradford Metropolitan

District Council have worked as partners on a

number of initiatives to foster the regeneration

of Bradford’s city centre and inner city

suburbs. Since 2012 the Little Germany area

has been identified for special attention. It

abuts the stalled Westfield Broadway retail

development and its unique townscape has

suffered some decline as a result of the hiatus

on the neighbouring site.

Little Germany is arguably the most

impressive merchant quarter in Yorkshire.

It developed in the mid-19th century as a

result of Bradford’s manufacture of textiles,

which were highly desirable to the continental

market. German merchants, in particular,

were keen to trade in the town and established

themselves outside the centre on undeveloped

glebe land (farmland assigned to an

incumbent clergyman), in easy reach of both

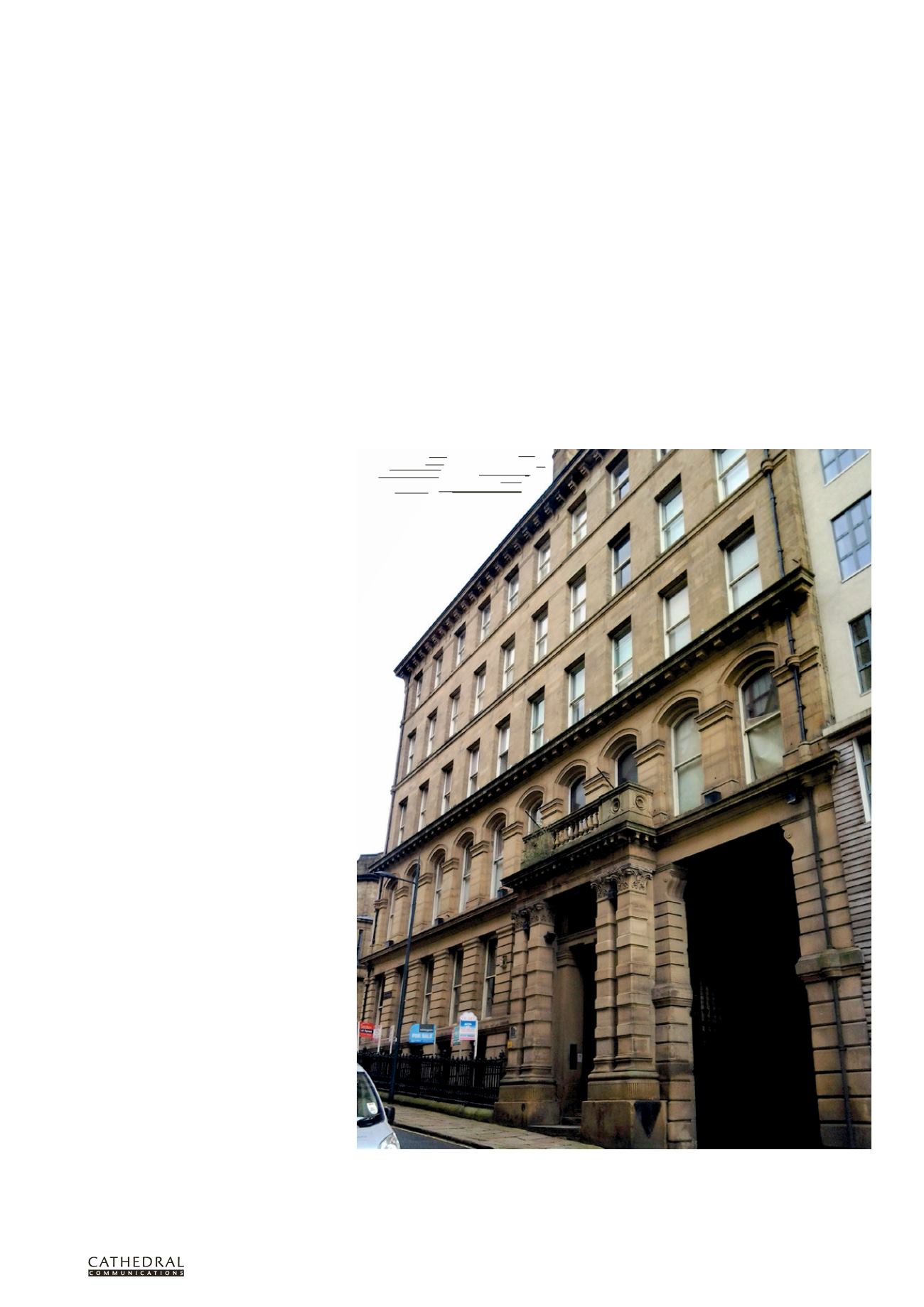

Bradford’s Little Germany was established in the mid-19th century by German merchants who were keen to

forge links with the city’s textile industry. A local listed building consent order, which could be in place by the

spring of 2015, would simplify and speed up the approval process, helping to bring these buildings back into

beneficial reuse.