T W E N T Y S E C O N D E D I T I O N

T H E B U I L D I N G C O N S E R VAT I O N D I R E C T O R Y 2 0 1 5

8 1

3.1

STRUCTURE & FABR I C :

ROOF I NG

REPAIRING SCOTTISH SLATE ROOFS

MOSES JENKINS

S

COTTISH SLATE

roofs have a number

of characteristics which make them

well suited to both the local climate and

the nature of the material produced by slate

quarries in Scotland. These include features

such as diminishing courses, random lengths

and widths of slate, single nailing and laying

onto sarking board rather than battens

(Figure 1). When repair work is being carried

out to Scottish slate roofs it is important that

these differences are understood and work

specified accordingly.

It is also important to treat the roof

as an integrated whole rather than a series

of distinct elements. As well as the slate

covering, the sarking board onto which the

slate is fixed, lead flashings, ridges and a range

of other features are all integral to the proper

functioning of a roof. All of these elements

should be considered when repairs are being

specified and carried out.

SCOTTISH SLATE AND SLATING

While some Scottish quarries produced

slates in standard sizes, most produced

slates in random sizes and thicknesses.

The latter were generally intended for

the domestic market although some were

exported. Slates of all sizes and grades,

including those of random width and length

were, on occasion, also imported from

other parts of the United Kingdom which

saw Scotland as a market for this output,

although this was never common practice.

Variations in the size of slates from

Scottish quarries led to the practice of laying

the material in ‘diminishing courses’, ensuring

the most efficient use of the quarry output. This

means that the largest slates are laid at the base

of the roof with the smaller slates laid nearer

the ridge. The slates were fixed in place using a

single nail in the centre of the slate head. Slates

were trimmed at the shoulders of the head to

make it easier to move slates aside to access any

that were broken or damaged. This type of slate

is known as ‘squared and shouldered’ (Figure 2).

The pattern of a Scottish slated roof is dictated

by the size of the slates and although it has

a distinctive character, this varies from one

building to another.

A further difference in Scottish slating

practice is that Scottish slate roofs are almost

always laid onto sarking boards rather than

onto battens. Such boards were laid with a

‘penny gap’ between each board – a gap of

about the thickness of an old penny. The gap

performed the twin function of allowing

for any expansion and contraction within

the wood, and keeping the roof space below

well ventilated and allowing the dispersal of

occasional wind-driven rain from under the

slates, keeping the adjacent timber dry and

free of decay.

SURVEY AND INSPECTION

As with any building element, regular

inspection of Scottish slate roofs will allow

emerging repair issues to be tackled early

(Figure 4). Repairing small problems as they

arise will help avoid the need for larger, more

costly repairs in the future.

A detailed roof survey should be carried

out prior to any repair work taking place to

ascertain whether localised patching or full

re-roofing is required. This will include taking

photographs to ensure that the pattern of the

roof is maintained in any required work. The

scope of work should then be agreed with a

contractor, allowing for the likelihood that

when work starts it may be discovered that

slightly more slates than first anticipated will

need to be replaced. A common cause of a need

to re-slate a roof is ‘nail sickness’, the rusting

away of the nails which hold the slates in place.

This might be due to poor quality or simply

age. Depending on the quality and durability of

the slate, decay and softening of the top of the

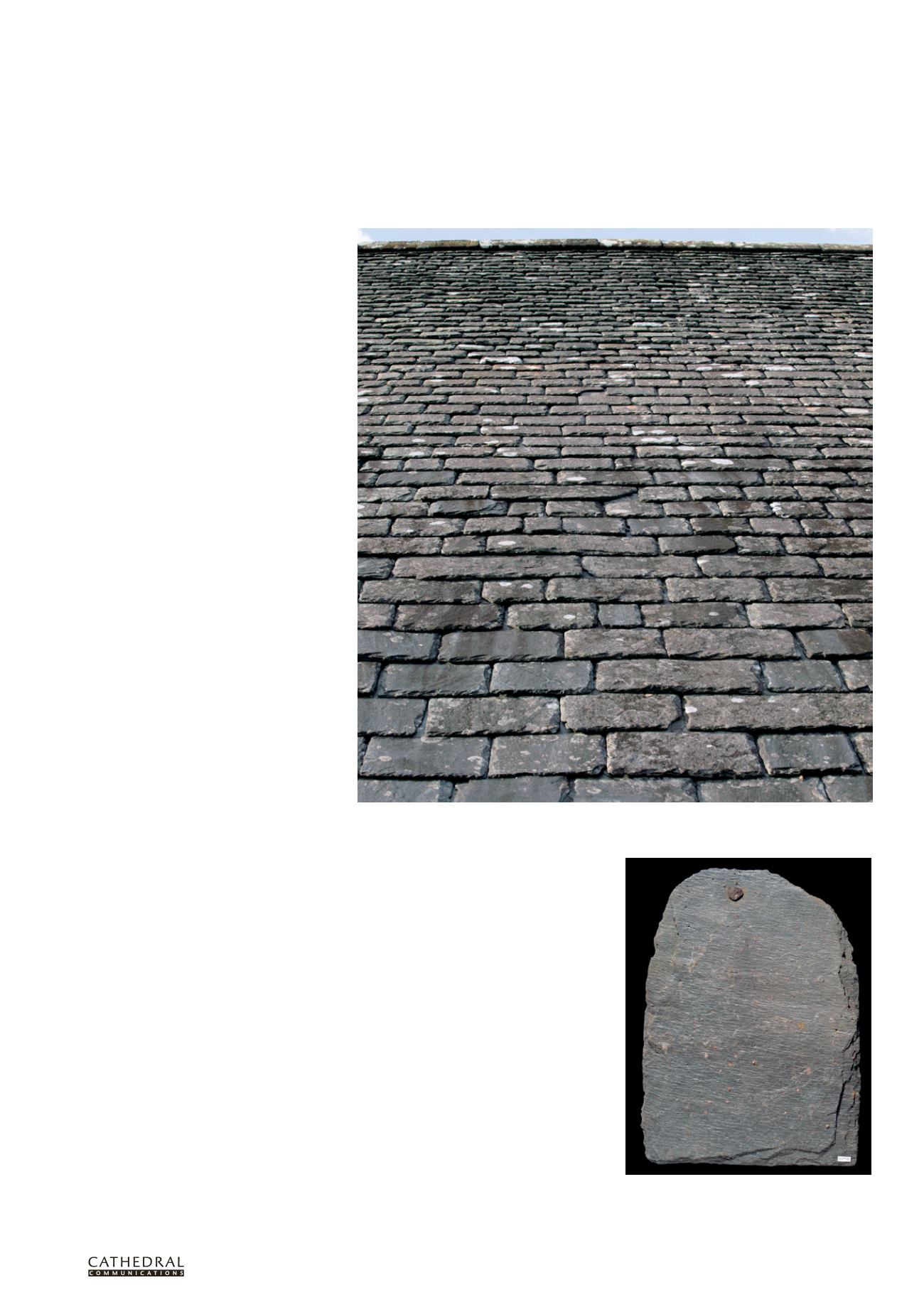

Figure 1 Scottish slate roofs, constructed to traditional patterns and details, have proven to be durable and

long-lasting.

Figure 2 A squared and shouldered Scottish slate

with a single nail hole