T W E N T Y S E C O N D E D I T I O N

T H E B U I L D I N G C O N S E R VAT I O N D I R E C T O R Y 2 0 1 5

8 3

3.1

STRUCTURE & FABR I C :

ROOF I NG

decreasing to under 50mm at the top of the roof

to allow the smaller slates to lie properly.

The varying widths of slate mean that an

even side lap cannot always be maintained.

(The side lap is the distance between the

edge of a slate and the edge of the slate which

it partially covers in the course below.)

Generally the side lap is worked out by placing

the perpendicular joint between two slates in

a course approximately centrally to the slate in

the course below. In practice, this is difficult

to maintain with slates of varying sizes so it

is usually assumed that the side lap will be at

least 50mm. One and a half slates are often

used on the edges of the slopes, while narrow

bachelor or ‘in-bands’ slates are used mid-row

to regulate the side lap.

Slates should be single nailed as in

traditional practice. Fixing with non-ferrous

nails is likely to prove more durable in

the long term and copper nails are often

specified. Traditionally it was usual to

‘cheek nail’ (or side nail) every sixth course

to help keep slates in place and T-shaped

nails were manufactured specifically for

this purpose. In exposed areas or on turrets

this can be increased to every three courses.

This practice is likely to be beneficial

in repair work. In some cases slates in

exposed areas are bedded in mortar to keep

them in place, particularly when working

with smaller sizes nearer the ridge.

REPAIR OF LEADWORK ON

SCOTTISH SLATE ROOFS

The correct repair of leadwork is a subject

in its own right but it in the context of slate

roofs it is an important part of the works

and should always be done at the same

time. As mentioned, lead is often used in

situations such as valleys and at points where

masonry such as parapets and chimneys

meets slate roofs. Where such leadwork

is being repaired it is important that it is

correctly detailed and secured and that lead

of a sufficient thickness (or ‘code’) is used

to ensure a durable repair. For example,

Code 7 lead is recommended for valleys.

Relevant trade association guidance

should be consulted and Scottish practice

in this area followed when repairs are being

carried out. On many traditional roofs mortar

skews were used, and while their replacement

with lead is likely to result in a more durable

repair, the change in material, and the

angles in which the slates sit will change the

appearance of the roof (Figure 11).

RIDGES

The ridges of slate roofs are an area of

vulnerability and are treated in a number of

ways. Lead is often employed along ridges,

applied over a timber former called a ridge

roll. Where cost is an issue zinc ridge of

standard length can be used. In some cases

ridges are formed of terracotta or stone. Any

repair or replacement should be carried out

using like-for-like materials to ensure that

the visual integrity of the roof is maintained.

Whatever material is used it is important to

ensure a firm fixing or bed to aid the securing

of the smaller slates at the top of the roof.

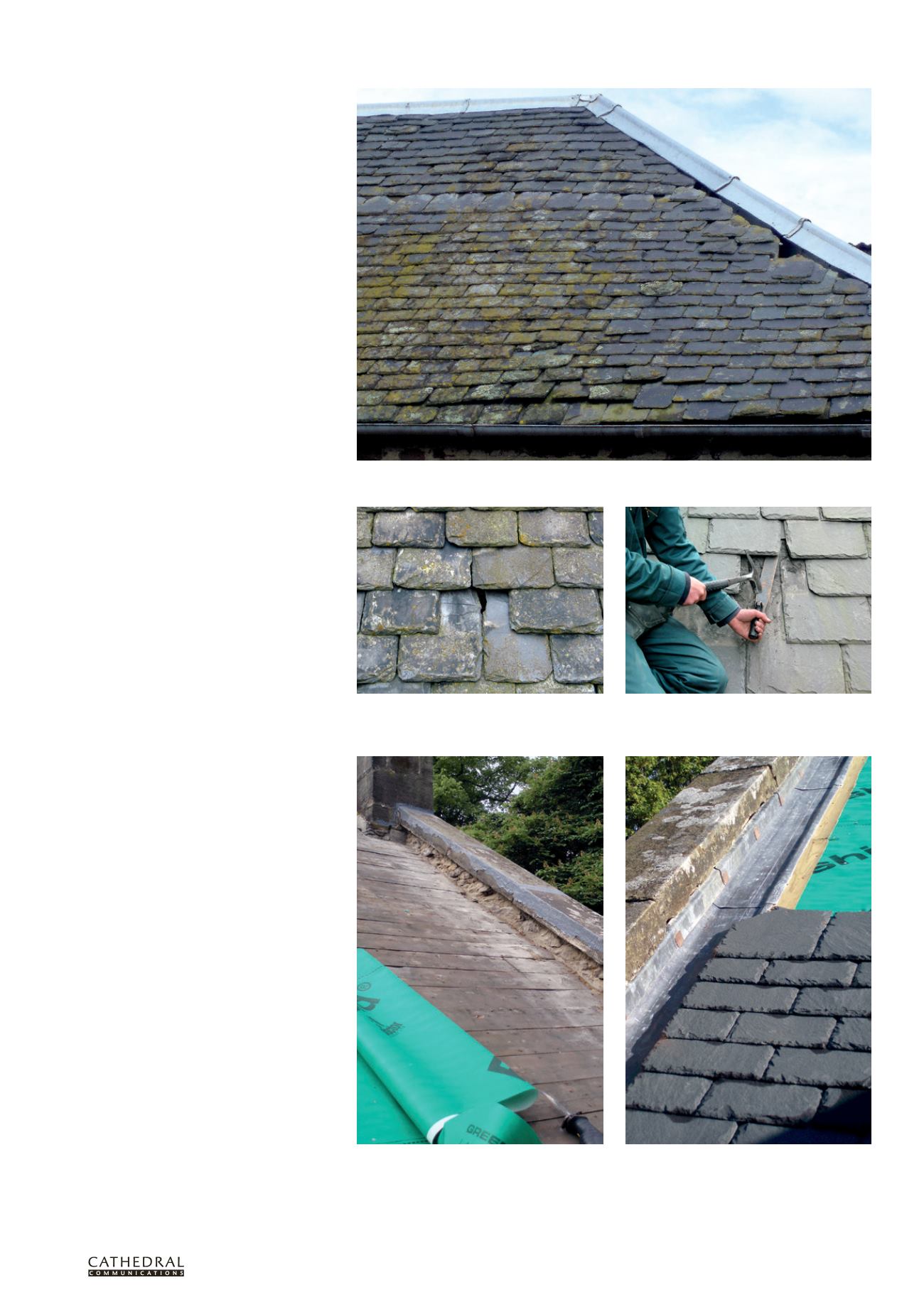

Figure 8 Individual missing slates can be patch-

repaired fairly easily using single nailing. The double

lap characteristic of Scottish roofs is also evident.

Figure 9 Removing the head of a broken slate using a

slate ripper

Figure 10 These sarking boards are in sufficiently

good condition for replacement slates to be laid onto

them with the addition of a breathable membrane.

(Photo: WD Cameron Slaters)

Figure 11 Lead detail at a gable parapet

(or ‘skew’) installed during re-slating work

(Photo: WD Cameron Slaters)

Figure 7 Where a roof has suffered the loss of many slates and is showing signs of further deterioration,

re-slating is likely to be required.