Modern Lime

Roz Artis

|

||

| One of the modern vertical shaft kilns at the Saint-Astier limeworks in the Dordogne, an area with a long history of hydraulic lime production. Limestone from the same geological source was exploited by the Romans at Perpignan over 2,000 years ago, and this plant dates from the 1850s. Here the company is still “cooking the lime” (as they would say) using coal from South Wales, but in a more controlled environment which maximises fuel efficiency. (Photo: CESA) |

Throughout history the building limes of the day were the modern limes of their time, and the basic building limes we use now (primarily natural hydraulic limes) are the modern limes of our time. It may be that the method of processing limestone into building lime has become more modern and calcination is better controlled, but it still employs the same raw ingredients of limestone and fuel. While coal is still favoured by the larger sites on the continent for the production of natural hydraulic limes, the kilns are more usually gas fired where clean high calcium limes are concerned.

Historically, the primary objective was to make lime more efficiently, using less fuel and less labour. Of the 14 kilns at Charlestown, Fife, six date from the 1760s and are of modest size, but these were soon superseded in both size and efficacy by the building of the first of the larger kilns (Kiln 11), which allowed larger volumes to be processed. This led to the construction of three more kilns – each bigger and better than the last. Confidence in lime burning had clearly increased exponentially, and ambitions had increased.

Research published by Historic Scotland (in Charlestown Limeworks Research and Conservation, 2006) highlighted the case of William Shaw, an architect of Bo’ness who wrote to John Grant in 1787 “to inform him that one third of his cargo of limeshells had had no lime in it all. Grant blamed this occurrence on the improper manner of burning the stone.” Clearly, the room for error was huge back in the day. As each lime burner was paid by piece work (how much they could produce), the temptation to speed up the process meant that they would throw more coal into the equation resulting in over burnt lime, of no use to anyone. (A possible exception is the icehouse at Broomhall, the seat of the Earl of Elgin, which is decorated with the glassy nodules of over burnt limestone.)

|

||

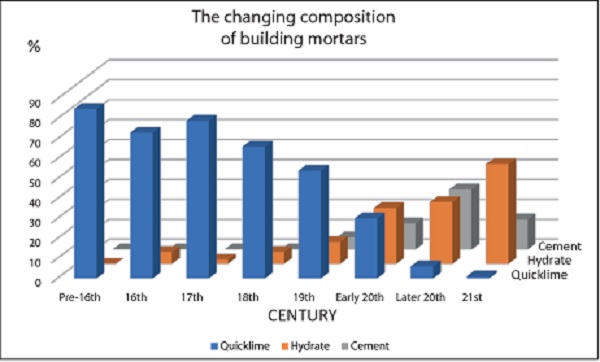

| Analysis of the Scottish Lime Centre’s database of mortar samples shows the declining use of quicklime as the basis for making mortar as it was gradually superseded by the use of lime hydrate and the early cements of the late 19th century onwards. |

In a recent joint project with Historic Environment Scotland (not yet published), an analysis of the Scottish Lime Centre’s archive of over 4,000 samples of mortar showed that, over time, the use of quicklime as the basis for making mortar was gradually superseded by the use of lime hydrate (quicklime slaked to a powder) and the early cements of the late 19th century onwards. With a growing array of means of transport, previously limited to boat, ship and horse and cart, the transport of hydrated lime (twice the weight of quicklime for the equivalent volume) was made much easier and would have been less hazardous than transporting large volumes of quicklime (not the favoured cargo of ship masters). At Charlestown Limeworks, there was a hydrating plant at the kiln heads dating from the early 1800s, where the quicklime was treated with a controlled amount of water over several days to produce a powder, which would then be bagged and sold. Many of the Scottish ports, for example Leith, Perth and Montrose (and other ports around the UK) had lime shades, covered areas where loads of slaked lime (in powder form) could be stored and sold casually through the year.

It wasn’t always the case that mortars were hot mixed by slaking quicklime with water and sand for immediate use. In many cases and particularly for the stronger hydraulic limes, like that produced at Charlestown, the quicklime was slaked with a limited amount of water to a dry hydrate and left for a few days (it’s only the free lime that slakes, not the hydraulic components) to ensure the slower slaking particles were fully slaked, otherwise, it risks remaining as an unstable material. This same method was used recently by Scottish Lime for repairing a medieval wall at Culross Palace, Fife. We burnt the local Charlestown lime and slaked it over a few days to a hydrate, then made it into a mortar with local sand and water. The resulting mortar was very plastic and workable suitable for both re-building and repointing masonry.

It is worth mentioning that all UK lime production today is of high calcium or air lime (CL80/90), because its high purity is prized for steel fluxing, water treatments and ground consolidation works. These are hard burnt limes (over 1100°C) and can often contain particles that are slow to slake, resulting in disrupted mortars if made as hot mixed mortars and used too soon after mixing. The Romans made a law that lime to be used for plastering should be matured for at least three years. We should take heed of these past practices.

|

||

| A colour matched lime based one-coat render system was selected for the north-facing roadside elevation on a very busy street with a narrow pavement, the other three elevations are traditional lime harl and limewash. To the untrained eye, there is no detectable difference. |

In terms of modern lime products available today, we have an enviable range to choose from, some designed for particular purposes, for example grouting, surface repair of brick and stone, one-coat render systems or just plain binders for making simple site mixed mortars. Many of our traditional mortar suppliers have ventured into producing an ever-increasing range of ready mixed, dry bagged mortars pertaining to their local area and utilising local sands and aggregates. These offer more reliable and consistent products that removes the chance of error in accurately proportioning out binders and sand on site. One contractor recently compared them to ‘Pot Noodle’: “you just add water – it’s a no brainer!” Incorrectly proportioned lime and sand mortars are in our experience a primary culprit in the failure of lime mortars, as well as the inadequate aftercare and protection of some which is often left to chance. They can also be a convenient solution where city centre sites have limited space for preparing mortars on site.

In the 2010 revision of the EN 459:1 standard for building limes, two new categories were introduced, namely HLs (hydraulic limes) and FLs (formulated limes) which gave producers the opportunity to create binders with more exacting results than ever before, by the addition of other ingredients such as low sulphate cement or pozzolans (for earlier stiffening), air-entrainers, carbonate dust (ground chalk or limestone), water retainers and water repellents. In the case of HLs, the manufacturer is not required to reveal the individual constituents, and so is able to protect their secret recipe. In the case of FLs, these are a blend of constituents with a declared composition including cement. In reality, there are only a handful of HLs and FLs available in the UK (St Astier’s HL5 Hourdex, Tradiblanc and HL3.5 Tradeco, for example), although many more are available in continental Europe. While these newer products are primarily designed for new build applications, conservators have found them to be of use when trying to emulate the properties of early patented cements (now no longer made), where appropriate.

|

|

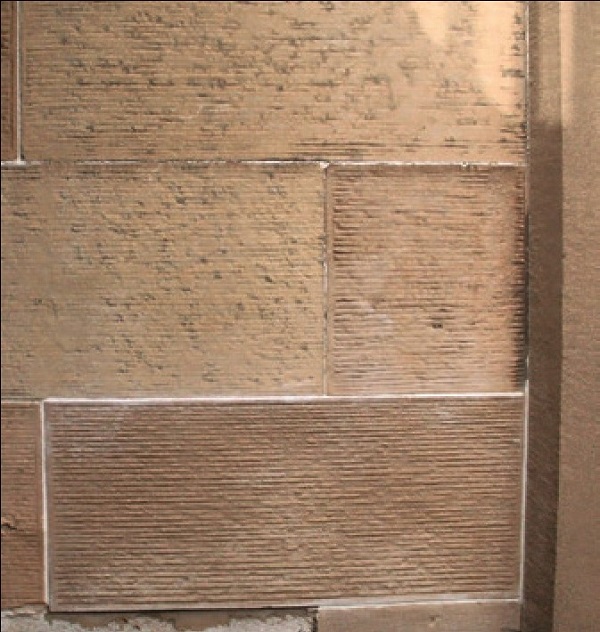

| Due to erosion, a like-for-like traditional white ashlar mortar in the now widened joints of this church spire would have changed its character dramatically, and site conditions dictated the use of a carefully formulated hydraulic lime mortar to suit the harsh environment. | A mortar formulated for the surface repair of stone (or brick), colour matched to the original stone. |

The addition of water retainers is particularly useful in lime mortars as they prevent over-rapid drying, reducing the risk of shrinkage cracks. Water retention will also help a hydraulic lime mortar to acquire strength slowly by avoiding desiccation. It is of particular note that hydraulic lime mortars should be kept damp for at least 72 hours after placing to ensure the hydraulic set forms. If a mortar is allowed to dry out within this 72 hour period, re-wetting will not re-initiate the hydraulic set. Water retainers are particularly useful on high suction backgrounds or where protection of the new mortar work is particularly difficult to achieve.

Illustrated here are three examples of modern lime products used in the context of building conservation, restoration, repair and renovation. In the case of the church spire (top right illustration) using a like-for-like mortar would have been a catastrophic mistake. For budget reasons, it was not possible to fully scaffold this spire and so we were forced to design a mortar that fulfilled the brief of appropriate repair, both technically and aesthetically and in a particularly challenging environment. Furthermore, the once fine joints were now much wider due to erosion, so if pointed with a traditional white ashlar mortar which matched the original, the joints would have been visible from the moon, detracting from the original design. Instead, we formulated a mortar based on NHL 5, with an air entrainer (reducing the strength down to the equivalent of NHL 3.5), colour matched to the building stone with a red iron oxide pigment and with a water retainer (as it was impossible to secure close covering for protection of the mortar as it was curing).

In conclusion, there is a place for all mortar types be they hot or cold mixed, formulated or dry mixed ready bagged mortars, the specifier just needs to be fully informed and that’s up to each individual to investigate. And with 25 per cent of professional indemnity insurance claims being specification related, it’s well worth the effort.