Victorian and Edwardian Stencilled Decoration

Kevin Howell

|

|

| Stencilled decoration above the arch to the Chapel of the Blessed Sacrament; St Giles’ Church, Cheadle, Staffordshire by AWN Pugin (Photo: Kevin Howell) |

The use of stencils for applying motifs and decoration to surfaces has a history that stretches back at least to the Upper Palaeolithic era nearly 40,000 years ago. The earliest confirmed examples are hand stencils in the Cueva de El Castillo in Cantabria, northern Spain, where recent analysis led by Dr Alistair Pike of Bristol University has determined that the images are at least 37,300 years old.[1] These negative images of hands were created by spraying pigment blown from the mouth over a hand held against the rock, possibly using a reed or bone pipe to direct the spray. They can be found all over the world and appear to have been of great significance to our ancestors.

The development of cut-out stencils allowed greater versatility. They have been used for applications as diverse as decorating buildings and artefacts by the ancient Egyptians, Greeks and Romans; for producing beautifully patterned textiles in China and Japan; and, more recently, for graffiti and the mundane marking of packing cases and military hardware.

By the Middle Ages stencilling as a decorative technique had spread to Europe and England via trade routes from the east and through crusades and pilgrimages. As the principal patron of the decorative arts, the church was quick to adopt stencilling. One of its many uses was for the decoration of devotional objects for the flourishing trade created by pilgrims keen to acquire a memento of their journey. Perhaps most recognisably today, however, it was used for the decoration of churches, cathedrals and other important buildings.

|

|

| Late-medieval lead stencil of a six-petalled flower, 80mm

in diameter, possibly used as a centre for each block in

a stylised ashlar pattern. (Photo: ©The Trustees of the British Museum) |

Stencilling was ideal for painting the repetitive ornament of friezes, borders, diapers, the enrichment of mouldings and patterning of panels. The great advantage was that it allowed the accurate, speedy reproduction of designs, supplemented by the graphic quality imposed by the hard-edged nature of the technique. Once the design had been determined, the execution could be entrusted to any competent craftsman, leaving the more skilled and artistic to concentrate on other demanding tasks such as figurative work.

In late 15th-century France the simple stencilled forerunners of modern playing cards were introduced, and in Rouen in the 17th century stencilled sheets of heavy paper anticipated the development of wallpaper. However, in England, although stencilling continued to be used for various purposes, the really significant catalyst for its use in the decoration of churches occurred in the early 19th century with the burgeoning of the Gothic Revival.

In the vanguard was the brilliant pioneer architect and designer AWN Pugin, perhaps best known for his enrichment and decoration of the rebuilt Palace of Westminster. He also used painted and stencilled decoration for many of his other commissions, both ecclesiastical and secular. Examples include St Chad’s Cathedral, Birmingham; St Giles’ Church, Cheadle; and the chapel at Alton Towers, Staffordshire. One of Pugin’s closest collaborators was John Gregory Crace,[2] whose firm Frederick Crace & Son carried out much of Pugin’s decorative work.

Pugin published the Glossary of Ecclesiastical Ornament and Costume in 1844 and Floriated Ornament in 1849, both containing designs for stencil decoration. An extract from Clive Wainwright’s preface to the 1994 reprint of Floriated Ornament is very informative:

If you read Pugin’s own clearly written Introduction you will see he argues that in the middle ages flat pattern was so successful because the plants were flattened and arranged in abstract rather than naturalistic ways. Pugin himself applied these principles to stencilling the interiors of his buildings, also to ceramics, wallpapers, carpets, curtains, furniture, stained glass and tiles… Designers from the 1860s like William Morris, Christopher Dresser and Owen Jones owed a great debt indeed to Pugin.[3]

It is this deceptively simple, twodimensional quality which gives stencilled decoration its timeless attraction. Another significant figure influenced by Pugin was the architect George Gilbert Scott:

Pugin’s articles [in The Ecclesiologist] excited me almost to fury, and I suddenly found myself like a person awakened from a long feverish dream, which had rendered him unconscious of what was going on about him.[4]

|

|

| St Mark, one of the Four Evangelists in an impressive late scheme which includes texts, shaded stencils and fictive mouldings; All Saints, Maidstone, Kent, with decorations by Clayton & Bell 1907-8 (Photo: Kevin Howell)St Mark, one of the Four Evangelists in an impressive late scheme which includes texts, shaded stencils and fictive mouldings; All Saints, Maidstone, Kent, with decorations by Clayton & Bell 1907-8 (Photo: Kevin Howell) | |

|

|

| Detail of the Sign of St Mark and a fictive moulding by Clayton & Bell 1908; All Saints, Maidstone, Kent (Photo: Kevin Howell) |

Scott was one of the most prolific architects this country has ever produced and from the 1840s onwards many young architects and designers were trained in his office. Some of the better known among them were George Frederick Bodley, Alfred Bell, Thomas Garner, George Gilbert Scott Jr, George Edmund Street and William White. As their careers progressed they carried Pugin’s ideas with them and put them into practice in their own buildings and decorative schemes.

The 19th-century preoccupation with architectural style led to the publication of many scholarly pattern books featuring designs suitable for stencilling such as Owen Jones’ The Grammar of Ornament published in 1856 and Polychromatic Decoration by W&G Audsley published in 1882, so there was no shortage of inspiration for architects and decorators.

Stencilled decoration developed broadly in tandem with the Gothic Revival and reached its peak of refinement around the turn of the 20th century. Depending upon the date and setting, mural decoration varied from simple ‘stoning and roses’ – stylised masonry patterns in earthy reds and ochres – to the most sophisticated multi-coloured schemes incorporating gilding, figurative subjects and complex symbolism.

In addition, reredoses, screens, organ pipes and cases, ceiling panels and roof timbers were all frequently embellished with stencilled decoration to emphasise their significance and disposition in the interior of the church.

In the golden age of Victorian religious conviction and imperial affluence some churches may have been completely redecorated every generation or so as fashions changed and the existing work began to look shabby. Sometimes two or even three decorative schemes lie one on top of the other. However, by the turn of the 20th century reaction to this was beginning to develop as may be seen from the strictures of the noted churchman and writer Percy Dearmer in The Parson’s Handbook, first published in 1899:

Stencilling is only an improvement when used with great reserve and by an exceptionally competent artist; it is safer to avoid it… The walls should be completely whitened, right up to the glass of the windows, and so should the tracery and arches...[5]

After the first world war there was widespread disillusionment with the certainties of a previous age. Gothic architecture in general was becoming unfashionable and there was little inclination to spend scarce money on embellishment. As decorative schemes started to show their age, increasing numbers were painted over or removed entirely. Although the use of stencilled decoration has continued to this day, the scale and sophistication achieved at its peak in the late Victorian and Edwardian eras have never been matched.

TECHNIQUES AND MATERIALS

Stencilling consists of applying paint to a surface using a stencil ‘plate’ to create an image, which can be positive or negative. Many materials have been used to make stencil plates: sheet lead, copper, brass, parchment, card, paper, and in more recent times, plastics. Almost anything can be used as long it is relatively easy to cut, and thin and flexible enough to lie in close contact with the surface, thus preventing the paint from creeping under the edges. Likewise almost any paint, dye or stain can be used as long as it is not too thin, so it does not run under the plate.

For architectural decoration in the 19th century, card or paper was generally used for stencil plates. The material was readily available and cheap, easy to draw on and to cut. Stencil brushes for applying the paint were usually round with the bristles formed into a stubby cylinder shape.

|

|

| Stencilled and freehand frieze in tempera, with oil-painted organ case above; St John the Evangelist, Sutton Veny, Wiltshire, by JL Pearson 1866-8, with decorations by Clayton & Bell (Photo: Jonathan Taylor) | |

|

|

| Above left: IHS stencil used in the restoration of the Lady Chapel, St Matthew’s Church, Westminster in 1984. The black lines are used to position the stencil correctly and the number of bridges to be painted out are kept to a minimum. Above right: Modern stencil brushes and a Victorian paper stencil. The paint has built up thickly on the stencil plate from repeated use. (Photos: Kevin Howell) |

As with most crafts, individuals would vary their technique to suit the job in hand, but the general procedure was much the same as it is today. The design is drawn onto the stencil plate and cut out with a sharp, pointed knife.

During cutting, ‘bridges’ or ‘ties’ are left to hold the various parts of the design together (for example, a letter ‘O’ stencil must have the centre held in place). The skill is for the bridges to be incorporated as an integral part of the design. Done well, this produces naturally elegant patterns and the bridges go unnoticed. Otherwise a great deal of time can be spent painting out the gaps left by the bridges in the stencilled image.

Setting out is the next important step. For example, to embellish a moulding with florets, a stencil of perhaps four florets might be used. The distance from the last floret to the end of the plate would be the same as that between the florets, so each time the plate is moved along the design is self-spacing.

If stencilling a large area of wall, it should first be marked out with a grid of chalk or pencil lines to show the position of each repeat of the pattern. The stencil plate is then fixed in the first position using pins or tape. The stencil brush is dipped into the paint and tamped out on a palette to get an even loading sufficient to coat the surface without leaking under the plate.

It is worth the time and practice it takes to do this quickly and efficiently because the stencil plate will then only need cleaning after several repeats of the pattern. Otherwise it would need cleaning after each use to avoid smudging, taking up valuable time. The stencil plate is then lifted cleanly away from the surface and moved to the next position, and so on.

If designed with architectural discipline, friezes, borders and panels can give visual structure and substance to large areas of plain wall. A complex scheme might include several colours and gilding, and stencils might be joined up to form continuous patterns over broad areas. Stippled shading was sometimes used to emphasise parts of a design or create the illusion of depth in a representation of a moulding or the centre of a flower.

With imaginative use, stencilling could impart lightness and delicacy to plain unrelieved surfaces and transform a comparatively simple building into one which appeared rich, refined and sophisticated. Along with its speedy application, these were all good aesthetic reasons for the use of stencilling in the decoration of churches.

CONSERVATION

Victorian and Edwardian stencilled schemes were most commonly, although not exclusively, carried out in two types of paint: oil paint or tempera – a water-based paint usually bound with glue size derived from animal skins and connective tissue, although gelatin, gum, starch or casein (milk protein) were also used as binders. There is no hard and fast rule but tempera schemes tend to date from the earlier Gothic Revival period and oil-based schemes from the middle and later years.

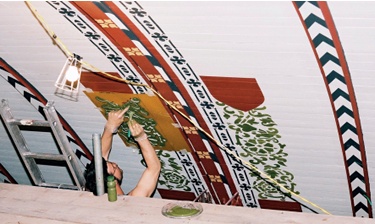

|

|

| Stencilling in progress during the reinstatement of ceiling decorations in 2005; Bedford School Chapel, Bedford, by GF Bodley (1827-1907) executed 1908-9 (Photo: Stephen Bellion) |

While tempera decoration has a ‘matt-ness’ and clarity which can to some extent imitate true fresco, it has the disadvantage of being readily soluble in water and can also be prone to abrasion. Consequently many schemes have suffered damage from damp ingress, wear and tear, attempted cleaning, and also deliberate removal. Oil paint has its own characteristic saturated appearance and lends itself to more developed decoration, including the addition of gilding. It is more resistant to everyday wear but due to its impermeability it, too, is easily damaged by the ingress of moisture. Over time, oil-painted surfaces can darken considerably by the accretion of dirt and through discolouration caused by atmospheric pollution.

If essentially sound, both tempera and oil-painted schemes can be successfully cleaned and conserved. A significant improvement in appearance can often be achieved by using dry cleaning methods, or aqueous or nonaqueous detergent solutions. Colours may also be obscured by darkened varnish or discolouration of the paint layer, which can be removed with solvents or specialist chemical solutions. However, there are risks attached to all cleaning so it is important that the painted surfaces should be investigated to determine the appropriate treatment in each case. For example, selecting the wrong solvent could dissolve not only the darkened varnish but also the original paint beneath it. With care though, decoration which has been overlooked for years can be given a new lease of life and appreciated once more as a valuable enhancement of its setting.

RESTORATION

Overpaint can sometimes be successfully removed so that original work can be conserved, and when this is possible it is clearly the best approach. In many more cases, however, problems are encountered: the underlying decoration may have been in poor condition when it was painted over; the overpaint may adhere tenaciously; or there may be later repairs or alterations which break through the decorative scheme.

|

|

| A cleaning test reveals the true colours of the chancel ceiling decorations; All Saints, Babbacombe, Devon, by W Butterfield 1872-4 (Photo: Kevin Howell) |

In such instances conservation can be prohibitively expensive. Equally importantly, it may be unrealistic to expect the result to be visually acceptable as a setting for worship. An alternative approach is to remove sufficient areas of overpaint to determine the original colours, patterns and setting out and to reinstate the scheme entirely. Representative areas can then be left exposed or protected with a sacrificial layer such as glue size or a dilute acrylic glaze as a record of the original work.

Stencilling is often considered to be easy to do, but this is a mistake which can lead to poor workmanship resulting in tawdry imitation of original work. It is absolutely crucial that any reinstatement must be a faithful reproduction of the original in every respect; accurate colours and designs executed with knowledge and skill. Anything less completely discredits the approach. Done well, reinstatement can be very successful, particularly in terms of the final presentation of the work.

CONSULTATION

A combination of conservation and restoration is often the best solution to the preservation of a decorated interior. It is therefore important before any work is undertaken to consult specialist conservators and restorers who are familiar with the type of work involved who can provide advice and guidance. Our surviving Victorian and Edwardian stencilled decorative schemes will then be well looked after and preserved for the future.

____________________________

Notes

[1] AWG Pike et al, ‘U-Series Dating of Paleolithic Art in 11 Caves in Spain’, Science, 336, June 2012, pp1409-1413

[2] R Hill, God’s Architect: Pugin and the Building of Romantic Britain, Allen Lane, London, 2007, pp315-316

[3] AWN Pugin, Floriated Ornament, Richard Dennis, Shepton Beauchamp, 1994, preface

[4] GG Scott, Personal and Professional Recollections, Paul Watkins, Stamford, 1995, p88

[5] P Dearmer, The Parson’s Handbook, OUP, London, 1932, pp69-70