Trust Funding

Timothy Finn

In addition to such obvious grant sources as English Heritage and the Heritage Lottery Fund, there are thousands of independent trusts. TIMOTHY FINN, a professional fundraiser, discusses how to approach them.

|

| Master Abbots Hospital, Guildford, Surrey. Trust funding was a key element in the financial package that secured the successful conservation and repair of these 17th century almshouses. (Photo: Bruce Watson, Master Abbot’s Hospital) |

At intervals over the past two years I have been trying to turn a promising thought into a pithy aphorism. The thought is a good one. The pithiness is the problem.

Now, just to make sure that the thought doesn’t become permanently stalled as it waits for the right verbal vehicle, I will share it with you in its unrefined form.

It is this: when we are raising funds for an historic building, or indeed for any major project, there are two methods to be considered. Method No 1 is to apply the technique which naturally occurs to us and Method No 2 is to seek contributions from grant making bodies. The largest of these are the government agencies such as English Heritage, Historic Scotland and Cadw, and other bodies such as the Heritage Lottery Fund, all of which will be familiar to readers of The Building Conservation Directory. In addition to these, there are several thousand smaller grant making trusts which, because of their number, cannot be approached in the same manner as the statutory bodies, and it is on these that I wish to focus in this article.

First, let us explore Method No 1 a little further. This is essentially an extension of our own style and character. It is the type of fund raising which best suits us and at which we are most likely to succeed. My late client, Sue Ryder, herself a great conserver of historic buildings, was an impressive embodiment of the principle. Having virtually invented the concept of charity shops, she then pursued her invention with such flare that the day-to-day operations of her international foundation became largely funded from this single strand of income. It was only when further funds were needed, often to give new life to an historic house, that Sue Ryder would turn to Method No 2.

This, then, is what my missing aphorism is all about. Once our natural strand of fundraising is up and running, grants should be our next port of call. Applying for grants clashes with no other activities. It complements the efforts of friends and colleagues.

THE TRUSTS SCENE

There are, in Britain, several thousand grant making trusts. The names, objectives, grant sizes and geographical preferences are largely available to us in published directories. At first glance the numbers seem so plentiful and the grants available so large that a newcomer might be forgiven for imagining that success is virtually guaranteed to a worthy application. Extend this principle across a range of, say, 50 to 100 applications and our funding problems should be solved.

Not so. Of all grant applications despatched to trusts, as many as 95 per cent will receive a rejection note. Quite simply, the level of requests which grant making trusts receive far outstrips their ability to respond. Often a grant making trust will receive more than 70 applications each week, of which two or three at most can receive an award. In these circumstances we need to consider whether we can devise a technique of approaching grant making trusts which will improve our prospects of success.

TRUST ATTITUDES TO GRANT MAKING

The trust grant making scene is fiercely independent. It has been well said that there are as many policies as there are grant makers.

Within this overall picture, there are certainly a good number of trusts which seek to make their awards on an objective evaluation of the needs. Complete objectivity, however, is by no means the only basis on which grants are awarded. After all, if grants are to be made purely on the basis of a score-based system, what is the role of the trustees in the decision process? Are trustees, with all their personal responsibilities and input of time, merely to rubber stamp conclusions which have been reached mechanically? Should they not be able to give weight to their own preferences, their own inside knowledge? The reality is that the personal preferences of trustees can have an important part to play in the distribution of grants. In some cases trustees are allocated sums to disburse at their own discretion, always provided that their awards fall within the charitable objects of the trust. In other cases, trustees’ preferences, subject to the same provisos, are paramount. Advocates of this approach can justifiably argue that little good is served by engaging staff at significant salaries to investigate the merits of an application, when a trustee can have intelligence of a worthy cause through the recommendation of a reliable acquaintance.

As we consider trust applications, we will do well to focus our attention on the wide range of trusts which may be amenable to a personal recommendation rather than on the rigid few which are locked into a mechanistic approach.

LAYING THE FOUNDATIONS OF OUR TRUST GRANTS CAMPAIGN

Now that we have a broad picture of how trusts think and act, we can start to lay the foundations of our campaign. There are three preparatory phases to be undertaken:

1. Project

Literature

We start by preparing our written case for support. This takes

the form of a printed brochure, normally, in the case of a conservation

project, with illustrations and floor plans.

This brochure serves two purposes: First, evidently, our brochure is designed to provide the administrative officer of a trust – normally called ‘the correspondent’ – with all the information he needs to prepare a summary of our cause for his trustees to consider.

Second, and scarcely less important, the statement of our case in writing will work wonders to firm up our aims and objectives in our own minds. By setting everything down in the form of a sparse text, we are compelled to eliminated all woolly thinking and all convenient fudges until we arrive at a diamond-hard case.

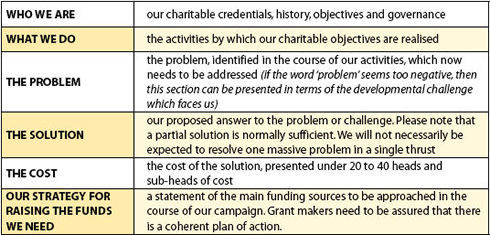

There is no virtue in novelty when preparing a campaign brochure. The following sequence of topics, each allocated approximately one A4 sheet of typescript will ensure that all the issues are covered. We may place whatever captions we please at the head of each topic. However, the underlying subject matter does not change:

2. Trust

and Livery Company Research

The published directories of trusts and livery companies provide

us with useful researched data. However, we need to refine this

further. In particular we need to identify grant making bodies

where we are likely to establish a personal connection with a

trustee or liveryman.

For this purpose, bearing in mind that we will be asking distinguished, voluntary supporters to peruse our finished research, we need to limit our listings to 125 grant making bodies at most. These are then presented in the form of three lists:

- Major, national trusts: a maximum of 50

- Local and regional trusts: a maximum of 50

- City of London livery companies: the top 25

3. Recruitment

of Patrons

Among our trustees and supporters we may well have several distinguished

people who are on terms of acquaintanceship with trustees of the

national and local trusts and with senior liverymen. These may

be asked to assume the role of patrons, an entirely honorary title

bestowed on those who are able to recommend us to grant makers.

Even if we have no such helpers, however, we can frequently secure

the assistance of appropriate people from our own county or neighbourhood.

Such is the good will and the sense of duty of these people that

several will normally agree to serve as patrons, provided we promise

to use their limited time to good effect. This is an assurance

which we can most certainly give.

Our plan should be to form a patrons’ panel of, say, 5 to 10 distinguished helpers. However, there is no need to delay fund raising until the whole panel has taken shape. As soon as the first patron has agreed to serve, we can at once embark on the active fundraising phase.

|

OUR CAMPAIGN IN ACTION

We visit our patrons one by one and discuss with each our list of researched trusts and livery companies. This is an intriguing exercise for both parties - especially for the patrons, who are often surprised to find that they do indeed know several of the leading trustees and liverymen whose names we have listed.

A well connected patron may know as many as 12 people on our lists, occasionally more. However, let us follow the process through in just one case. The steps we take in this example will eventually be repeated, again and again, as more trustees and liverymen are identified for personal approaches:

- Our patron writes to his trustee acquaintance to ask whether a formal application can be lodged.

- The trustee replies, encouraging us to send an application.

- We then prepare our formal application and post it to the trust’s correspondent. Our published project brochure and our audited accounts are enclosed as part of the application package. The exchange of letters between patron and trustee is clearly flagged up in the first sentence of the application letter. This will frequently ensure the progress of our application from the in-tray to the shortlist, in view of the declared interest of the trustee.

- Two to three months later the trust board meets to consider its awards. Our application is presented, in summary, to the trustees.

- Our patron’s acquaintance speaks in favour of a grant.

- A grant is awarded.

THE LATER COURSE OF THE CAMPAIGN

The steps I have just described may seem long and tortuous. They are, however, very accurate steps and it is by this sequence of events that the largest grants can normally be obtained. We should remember that, in a well-functioning campaign, as many as 80 or 90 connections may be identified by distinguished patrons out of the 125 we have listed for consideration. The administration of the multiple applications which arise from these connections occupies the main period of the campaign over many months.

Furthermore, where patrons’ recommendations prove successful in obtaining the larger grants, imitative grant-making from smaller trusts in response to ‘cold’ applications frequently adds significant extra income.

Recommended Reading

The Directory of Grant Making Trusts, Charities Aid Foundation

A Guide to Major Trusts, Vols 1 & 2: Directory of Social Change

Both of the above are available from The Directory of Social Change, Tel 020 7209 5151 The City of London & Livery Companies Guide: City Press, Tel 01206 545121 People of Today, Debrett, Tel 020 8600 8222

Useful Websites

Funds for Historic Buildings, www.ffhb.org.uk