T W E N T Y F I R S T E D I T I O N

T H E B U I L D I N G C O N S E R VAT I O N D I R E C T O R Y 2 0 1 4

1 2 1

3.3

STRUCTURE & FABRIC :

ME TAL,

WOOD & GLASS

The high performance wax coating penetrates and protects the whole metal surface, and its distinctive lustre

reveals the laminations of the historic material. It requires only relatively simple maintenance every five to

seven years to ensure protection.

sponges are dry cleaning sponges for use on

soiled surfaces. Dirt particles are absorbed

into the sponge’s surface which, in turn,

crumbles away during use.)

Three different coatings were tested:

tannic acid suspended in polyvinyl acetate

(PVAc), microcrystalline wax, and Waxoyl,

a hydrocarbon suspension of wax and

phosphoric acid rust inhibitors made by

Hammerite Products. These coatings offer

a good barrier layer between the ironwork

and the moisture in the atmosphere and are

relatively easy to maintain. Unlike flaking

paint, they do not require complete removal

before re-application. During the testing

process it was found that Waxoyl gave the best

result and appeared to be the hardest wearing.

During the cleaning tests a small amount

of linseed oil putty was applied to the coated

areas, with the purpose of assessing how well

the putty would stick to the various coatings.

The putty needed to provide a weather seal

between the external environment, the

wrought iron frame and the leaded glazing.

As expected, the tests showed that the putty

would not stick to the Waxoyl and therefore

another approach had to be considered for the

inside face of the ferramenta.

One solution was to treat internal

surfaces with tannic acid, with linseed oil

putty applied on top. Tannic acid is a well

established corrosion inhibitor for iron.

It works by transforming the destructive

iron (III) oxides into iron tannates, which

are stable compounds. However, the tannic

acid is known to cause corrosion of lead. To

ensure that the tannic acid did not affect the

lead matrix of the stained glass panels, two

layers of Paraloid B72 (20 per cent weight by

volume in a solvent of acetone and industrial

methylated spirits) were applied over the

tannic acid. Linseed oil putty could then be

safely applied to the sealed surface.

During the conservation process it was

noted that a number of the glazing lugs were

broken or extremely thin and delicate. It was

agreed that 21 new lugs would need to be

fabricated and fitted. However, the original

material, high-quality charcoal wrought iron,

is no longer available commercially, so

alternatives had to be considered. The

medieval bloomery technology of iron

smelting, where the metal was never melted,

leads to an inhomogeneous microstructure

as found in the samples taken from the

oculus. Variation was evident within the few

millimetres of a single sample. This type of

charcoal or bloomery iron smelted at low

temperatures, is relatively pure, with only

small amounts of carbon and phosphorus

absorbed into the metal, the former from the

fuel, and the latter from the ore.

One option was to make the lugs from

modern rolled/recycled wrought iron. The

recycled wrought iron available today is

generally puddled iron from the industrial age.

It contains slag inclusions and laminations,

and has a similar grain structure to charcoal

wrought iron. Charcoal-smelted bloomery

iron is surprisingly resistant to corrosion

in contrast to more recent iron and steel

in which sulphur from the use of mineral

fuels is retained within the metal and acts to

accelerate the corrosion process. The original

samples examined were also very low in slag

inclusions, which may serve as easy routes

for corrosion penetration. Furthermore,

due to the reclamation process modern

wrought iron varies widely in quality and

would be visually and metallographically

indistinguishable from historic repairs,

which might confuse future investigations.

The alternative option was to use modern

pure iron. Metallurgically there is little

difference between pure iron and wrought

iron other than the fact that the pure iron

does not contain fibrous slag inclusions. The

conservation benefits of using pure iron are

that it is close to wrought iron, of consistent

quality, and easily distinguishable from the

original material. After considering the

options the decision was made to use pure

iron. A historic repair to one of the glazing

lugs was used as the design basis for the new

lugs. A small design change was incorporated

into the new lugs, and all the new components

were also date stamped to make them easily

identifiable in the future.

Considering the slight chemical difference

between the wrought and pure iron, it was

important to minimise the risk of galvanic

corrosion. To do this, at least one of the three

corrosion causing factors – oxygen, water, or

direct contact between dissimilar metals –

had to be eliminated. Using techniques that

were originally used in the manufacture of

the oculus (surrounding the copper wedges),

lead paste (a compound of linseed oil and red

lead containing, by weight, 95% lead (II, IV)

oxides) was applied to the ferramenta to act as

a jointing compound and barrier between the

wrought and pure iron. The new lug was then

placed over the paste and locked into place

using iron wedges. The lead paste would act as

a seal preventing water ingress.

This brightly coloured lead paste was

allowed to harden for two weeks, and was then

toned down with a coating of black Waxoyl.

LOOKING AHEAD

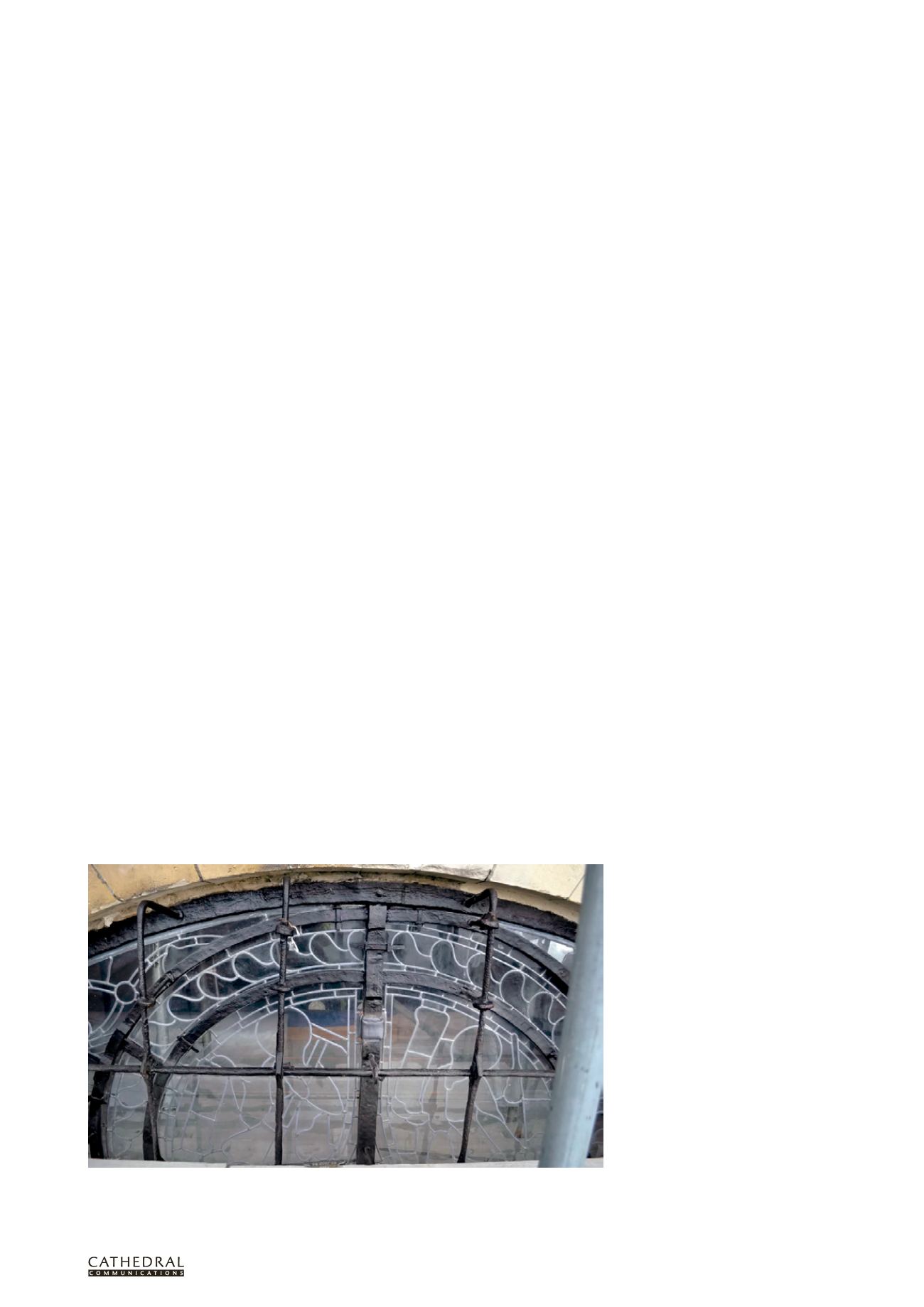

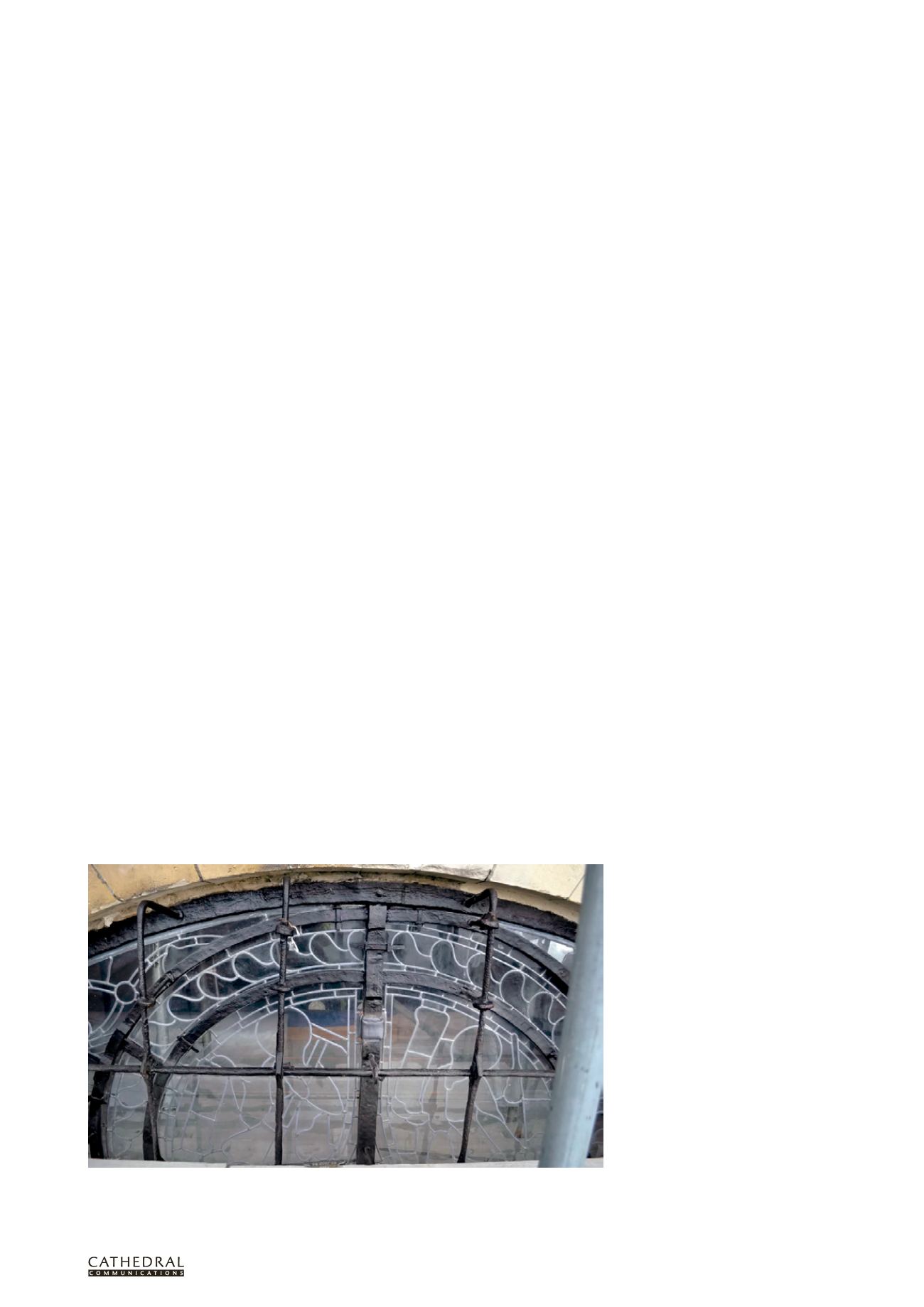

The south oculus ironwork had clearly

undergone some deterioration: localised areas

of more advanced corrosion were evident in

places, and substantial repairs had been made

to the ferramenta. However, it is a tribute

to the ingenuity and skills of the medieval

craftsmen that the iron window framing had

continued to fulfil its role for over 800 years. It

even survived damage received during World

War II bombing raids, when a section of the

ferramenta was effectively removed under

enormously high stress loadings, but the

integrity of the frame held.

Having carefully considered our options,

a high-performance wax coating (Waxoyl)

was chosen rather than either a traditional

or a modern paint system. The maintenance

of this coating could be carried out every five

to seven years, using a cherry-picker to gain

access to the oculus. The ferramenta and grille

would require a simple wash-down, followed

by re-application of Waxoyl. Paint systems, by

comparison, generally require more invasive

maintenance, including shot-blasting in the

case of the two-pack systems commonly

used, and all paint systems can trap moisture

when they crack or flake. We believe that high

performance wax coatings provide a good

balance of low-intervention treatment and

manageable maintenance. It is hoped that this

sympathetic approach to the conservation of

its 800-year-old ironwork will preserve the

oculus for many more centuries.

BRIAN HALL

ACR is managing director and a

senior conservator at

.

He has worked in the field of conservation

for the past 28 years specialising in sculpture

and architectural metalwork. He is also a

trustee for the National Heritage Ironwork

Group and tutor on the SPAB courses ‘The

Repair of Old Buildings’ and ‘Metalwork

Masterclass’.

The conservation and repair works to the south

oculus window were carried out as part of the

ongoing conservation works to the cathedral’s

stained glass windows and was assisted by a

generous donation by the Worshipful Company

of Ironmongers.