T W E N T Y F I R S T E D I T I O N

T H E B U I L D I N G C O N S E R VAT I O N D I R E C T O R Y 2 0 1 4

1 2 7

3.4

STRUCTURE & FABRIC :

EX TERNAL WORKS

TREES ANDTHE HISTORIC

ENVIRONMENT

SEBASTIAN WEST and ERIC HEATH

W

HETHER FORMING

an essential

part of the rural landscape through

forestry and agriculture, or providing

a dramatic vista within a designed park and

garden landscape, trees have long been valued

as part of the UK’s landscape.

Landscape design tastes have evolved

over time. Before the mid 18th century,

parks and gardens were very much in the

formal, architectural and geometric design.

For example, trees were laid out in strong

axial formal avenues radiating from the

principal house and feature points. It wasn’t

until the rise of landscape designer Lancelot

‘Capability’ Brown (1716–1783) that trees

became an essential instrument in producing

idealised sinuous and smooth views with the

use of tree clumps and belts among lakes,

ponds and rolling pasture. Brown’s idealised

landscape then gave way to the Picturesque

design movement in the late 18th century,

which appreciated the appeal of nature, the

rugged and the untamed. Ancient and veteran

trees� conformed to the aesthetics of the

fashionable gothic movement. Landscape

designer Humphry Repton (1752–1818) was

an advocate of the Picturesque style. In his

Observations on the Theory and Practice of

Landscape Gardening (1803) Repton recorded

that ‘The man of science and of taste will…

discover the beauties in a tree which the

others would condemn for its decay’.

During the Victorian period the more

formal Gardenesque landscape design

movement was introduced by Scottish author,

botanist and garden designer John Claudius

Loudon (1783-1843). This landscape design

style was subsequently adopted by many

public parks which encouraged the planting

of exotics and a range of interesting evergreen

specimen trees. The increasing popularity of

global travel among the wealthy meant that

exciting new species were planted and shown

off among fashionable society. Many of these

trees survive today in our parks and gardens.

During the early 20th century estates

began to be broken up and historic

parkland designs began to be eroded.

Forestry production also increased along

with clear-felling (the harvesting of all or

most of the trees in an area of woodland)

as part of the war effort. It was not

until after the Great Storm of 1987 that

people began to think increasingly about

repair and conservation of the historic

landscape and the trees within them.

Trees provide historic cultural connections

with people, events and places. They provide

a significant component in the history of the

British landscape, providing an aesthetic

value that cannot be underestimated. Trees

and their layout also help us to understand

parkland character and historic management

practices including use as medieval

hunting grounds, or for forming historic

hedgerows, pollards and coppice areas.

The English Heritage Register of Parks and

Gardens records those designed landscapes

which are nationally important and which

represent a material consideration for

local planning authorities in determining

planning applications. Similarly, there are

other ‘non-statutory’ registers which record

historic designed parks and gardens for

Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. Tree

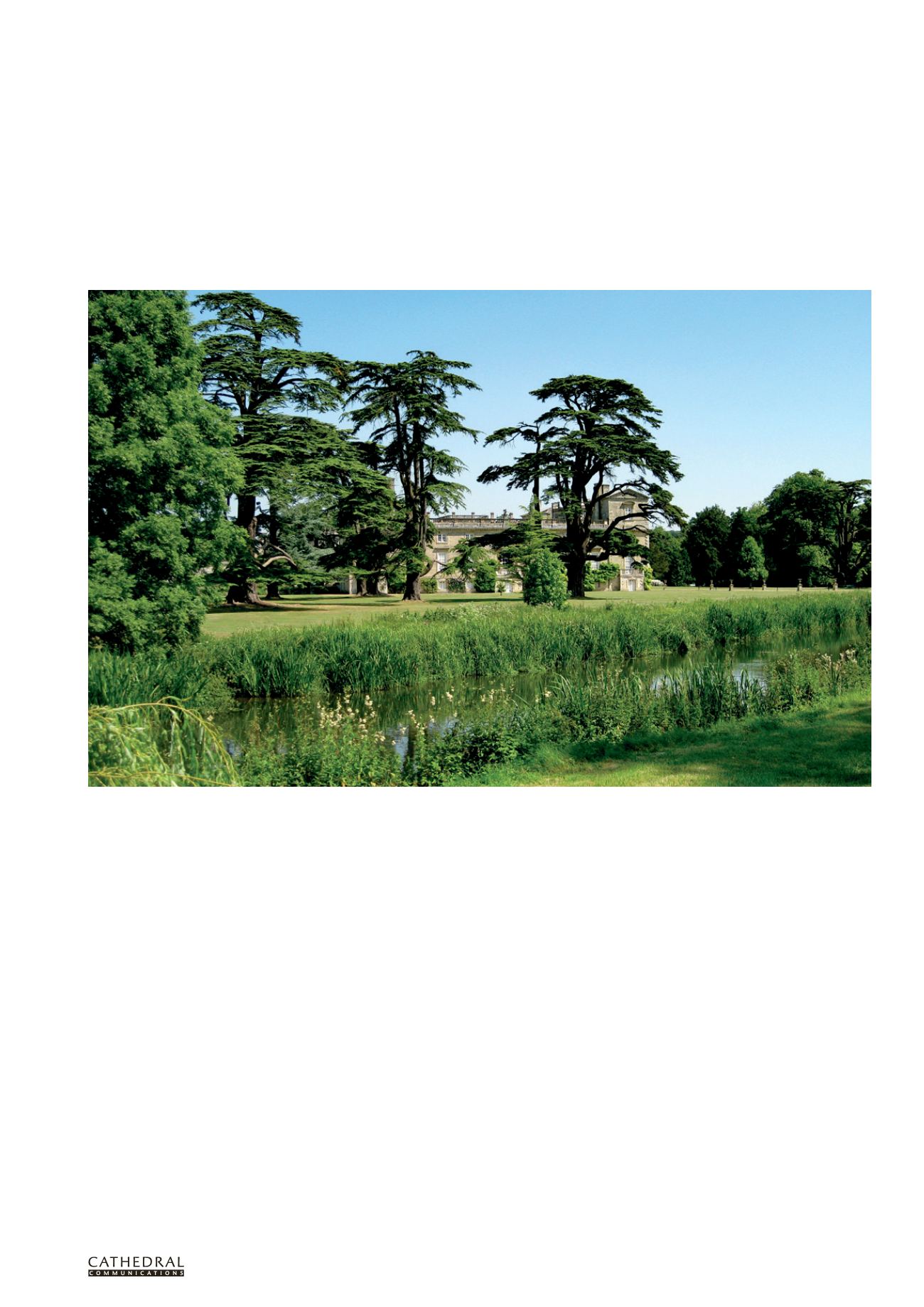

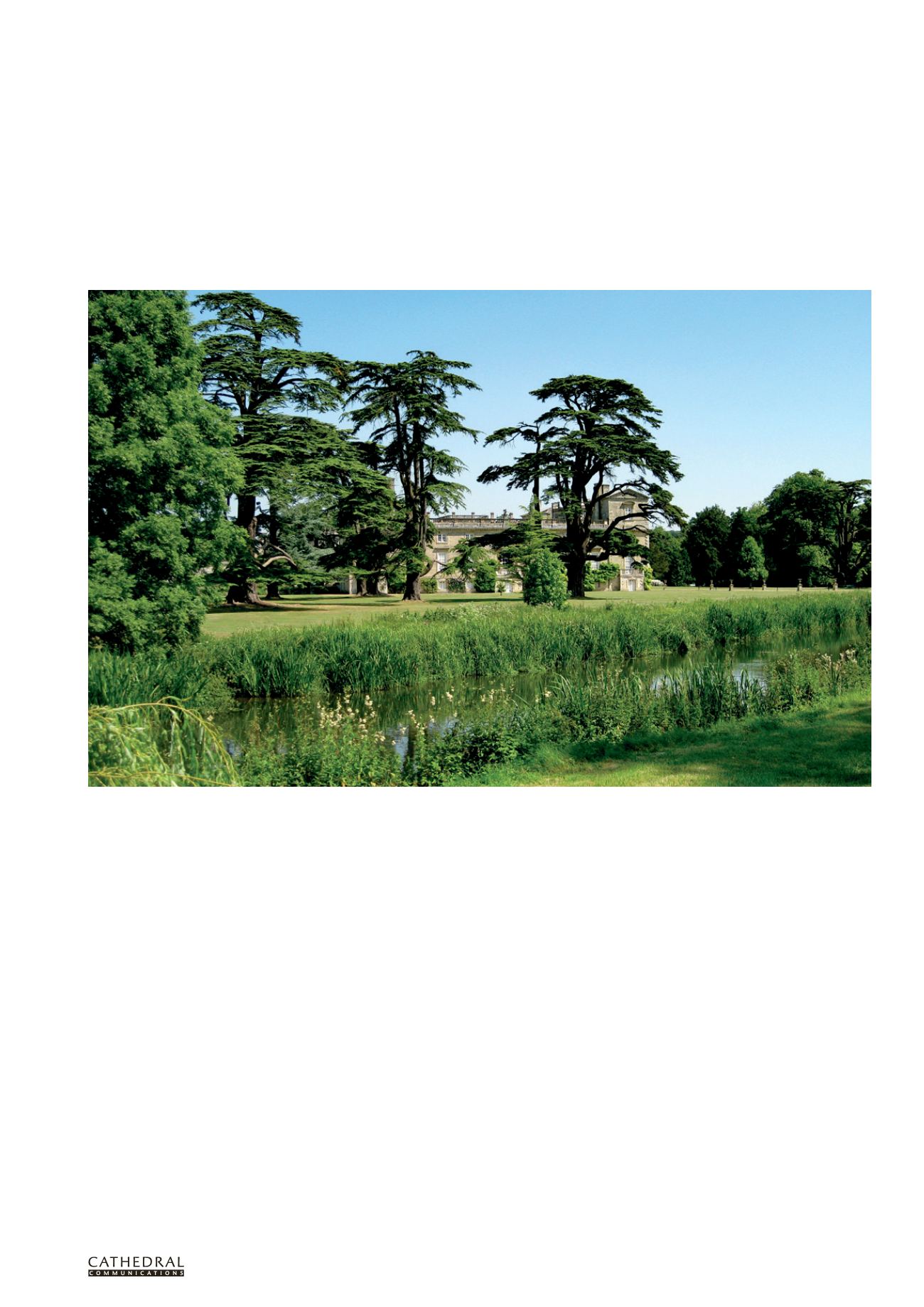

Parkland at Wilton House near Salisbury, Wiltshire (All photos: LUC)