1 3 6

T H E B U I L D I N G C O N S E R VAT I O N D I R E C T O R Y 2 0 1 4

T W E N T Y F I R S T E D I T I O N

SERVICES & TREATMENT :

PROTEC TION & REMEDIAL TREATMENT

4.1

CLEANINGMARBLE

MONUMENTS

ANGUS LAWRENCE

M

ARBLE HAS

long been an important

material for sculpture and

monumental compositions, notably

in religious settings. Whether related to a

significant event or as a mark of remembrance,

a monument will often become an important

focal element in an architectural space.

As with all natural materials, marble

is prone to varying degrees of soiling and

deterioration which in turn can be detrimental

to the appearance and appreciation of a

piece, detracting from its significance as

a work of art. Therefore cleaning aimed at

refreshing or restoring a marble surface is

often considered appropriate. As soiling

may also hide evidence of deterioration,

cleaning is often carried out as a precursor

to conservation and repair work, in order to

fully understand the condition of the piece.

Cleaning, then, often forms a necessary

and desirable part of a well-designed

conservation specification. This should

involve the simple removal of damaging

or disfiguring deposits from the surface.

However, cleaning is an irreversible

process and so the choice and application

of the right materials and techniques are

vital. Well-intentioned but damaging

cleaning has sometimes been carried out

in the past with the use of inappropriate

processes, tools and materials.

Faced with an ever-expanding group

of specialist marble cleaning products

(in the form of powders, liquids, gels,

pastes, etc) it is important to approach

the cleaning of marble monuments with

sound conservation principles and an

awareness that a historic marble surface

should be properly examined and assessed

before any programme of cleaning.

THE MATERIAL

Marble (from the Greek marmaros meaning

a white, shining stone) is a metamorphic

rock formed from limestone (CaCO

₃

) which

has been broken down under pressure and

heat to recrystallise and produce a granular

mosaic of calcite crystals of roughly equal size.

During this process, the original sedimentary

elements of a limestone are lost and a pure

marble is therefore monomineralic, free from

fossils and white in colour. The vast range of

coloured marbles is a consequence of small

amounts of impurities being incorporated

with the calcite during this metamorphism.

Marbles are found across the globe but

the best known and most desirable come from

Italy, Greece and Turkey. There are a handful

of true British and Irish marbles, but they are

relatively rare and most are only of geological

interest. Most notable are the rocks from the

Scottish islands of Iona, Skye and Tiree and

Connemara Marble from the west coast of

Ireland. Other stones that take a polish, such

as Purbeck, are often called marbles but are

in fact largely fossiliferous limestones, shale

stones and other varieties.

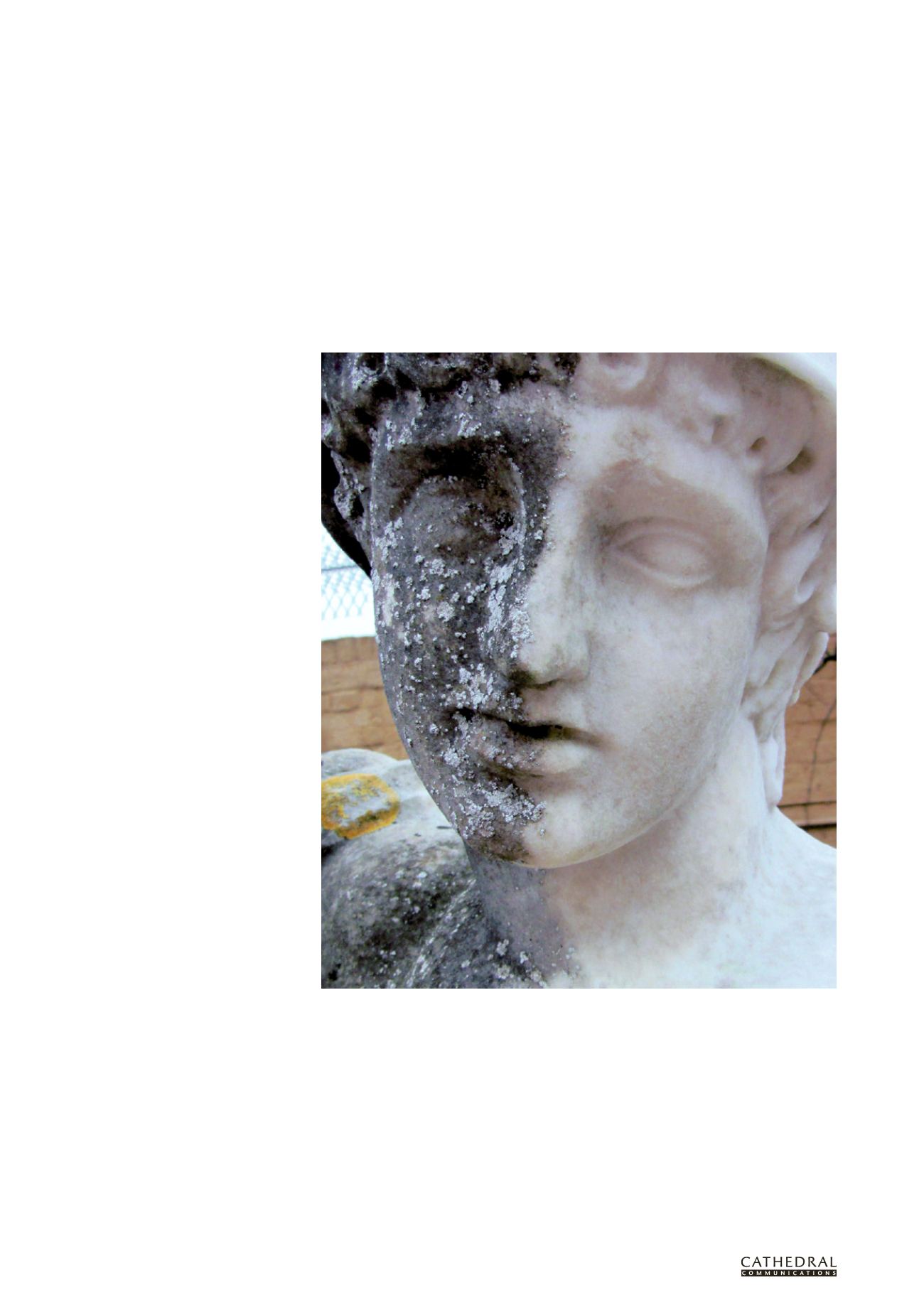

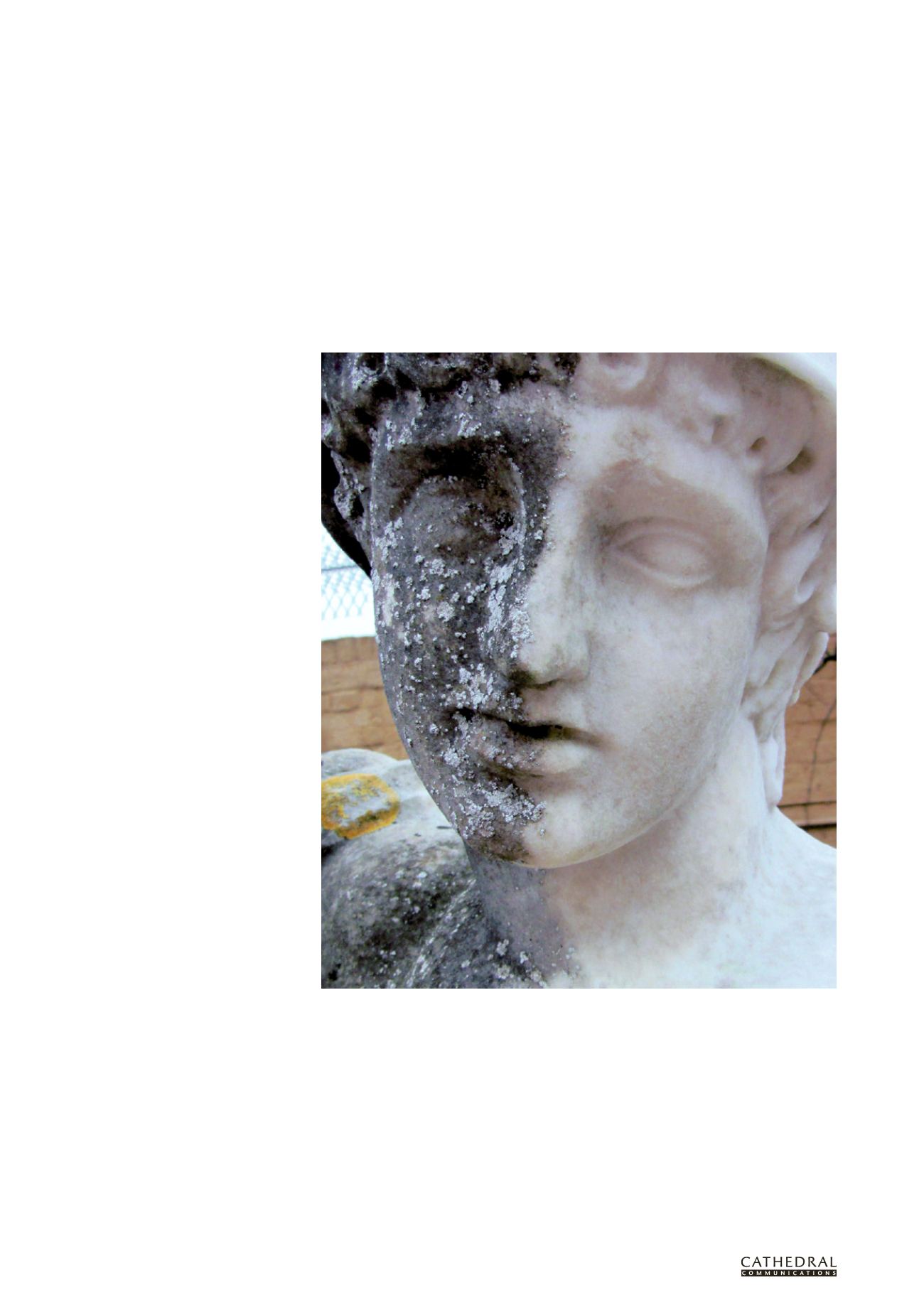

Eroded and soiled garden statuary marble, half of which has been cleaned using a controlled nebulous spray system

HISTORY AND USE

Since indigenous marbles are both difficult

to quarry and largely unsuitable for carving,

marbles from abroad have been an important

decorative and sculptural material in Britain

since the Roman occupation. Although the

architecture of ancient Rome is equated in

the popular mind with the use of marble,

the Roman buildings of Britain consisted

mainly of timber, local building stones,

and fired terracotta bricks and tiles, all

cemented together with lime mortars and