T W E N T Y F I R S T E D I T I O N

T H E B U I L D I N G C O N S E R VAT I O N D I R E C T O R Y 2 0 1 4

1 3 7

SERVICES & TREATMENT :

PROTEC TION & REMEDIAL TREATMENT

4.1

renders. Marble was, however, imported

around the Roman Empire in the form of

statuary, sculpture and monumental pieces to

furnish temples, public buildings and private

dwellings. Fine marble remains associated with

the 3rd-century AD Temple of Mithras, which

was excavated in 1954 in the City of London,

are on display in the Museum of London.

The use of marble tesserae in mosaic

flooring is also well recorded and in the

Middle Ages Italian craftsmen imported

material from archaeological remains in Italy

to reuse with indigenous stones in order to

achieve the decorative patterns and colour

combinations of the Cosmati pavements

at Westminster Abbey and Canterbury

Cathedral (both 13th century).

Alabaster was the main stone used

for religious sculptures and monuments

in Britain from the mid 14th century.

A vibrant and profitable industry grew up

in London, Nottingham, York and Burton

upon Trent and mass-produced sculptures

based on stock themes and imagery were

exported in large numbers to mainland

Europe. Sometimes mistakenly identified

and referred to as marble, alabaster is

geologically very different, being a form of

gypsum – hydrated calcium sulphate.

The 17th century saw the eventual

replacement of alabaster with marble as

the main material for church and other

monuments. Sculptural and architectural

styles based on European examples were

studied, copied and then developed in Britain

and the demand for marbles increased as

monuments became more exuberant and

ambitious in breaking free of the staid

conventions of the alabaster workshops.

A typical example of this development can be

seen at St Mary’s, Bottesford in Leicestershire,

where the use of alabaster for the fine

memorials to the Dukes of Rutland was

phased out in the middle of the 17th century in

favour of statuary marble.

Realistic portraiture became a

key component of many monumental

compositions with the finest statuary marble

being sought out to produce sculpture of

the very highest quality. Marble funerary

monuments were important commissions

for the top sculptors and carvers during

the late 17th century through to the late

19th century, with sculptors such as Gibbons,

Rysbrack, Westmacott, Flaxman and others

producing a range of monuments often

comprising large and complex architectural

arrangements. At the same time, fairly simple

marble wall tablets with incised and gilded or

painted inscriptions became commonplace

throughout the British Isles

.

The start of the 17th century also saw the

beginning of the use of marble as a decorative

feature for internal floors and walls, again

influenced by the architecture of Europe.

One of the earliest examples in Britain is at

the Queen’s House, Greenwich, where Inigo

Jones, who had returned from Italy in 1614,

used marble for the flooring in 1635. Dark and

brightly coloured marbles, which were deemed

unsuitable for sculpture, were often used to

decorate and enrich grand interiors.1

DURABILITY AND DEFECTS

Statuary marble has been used externally for

garden statuary and sculpture, churchyard

monuments and mausolea but its relative

vulnerability to frost and other atmospheric

conditions meant that limestones, sandstones

and granites became established as the

preferred materials for external stone pieces.2

Even in an internal location, marble

monuments are subject to a range of processes

that can cause deterioration. Moisture

is usually the key agent of decay, with

condensation or penetrating and rising damp

(often the result of a poorly maintained roof

or rainwater goods) leading to direct surface

erosion, soluble salt action and corrosion of

iron fixings.

It should be emphasised that the most

immediate consideration with any monument

is the structural integrity of the piece which,

if compromised, may constitute a significant

health and safety risk to users of the building

or surrounding area. Of major concern is

the corrosion and sometimes disintegration

of iron fixings, which can occasionally lead

to catastrophic failure. Larger monuments

may contain dozens of metal fixings, all

playing a role in keeping the various parts in

balance and uniting the whole as a coherent

Dust and soiling on a church monument caused by a

combination of atmospheric pollutants, waxes and

other applied surface materials

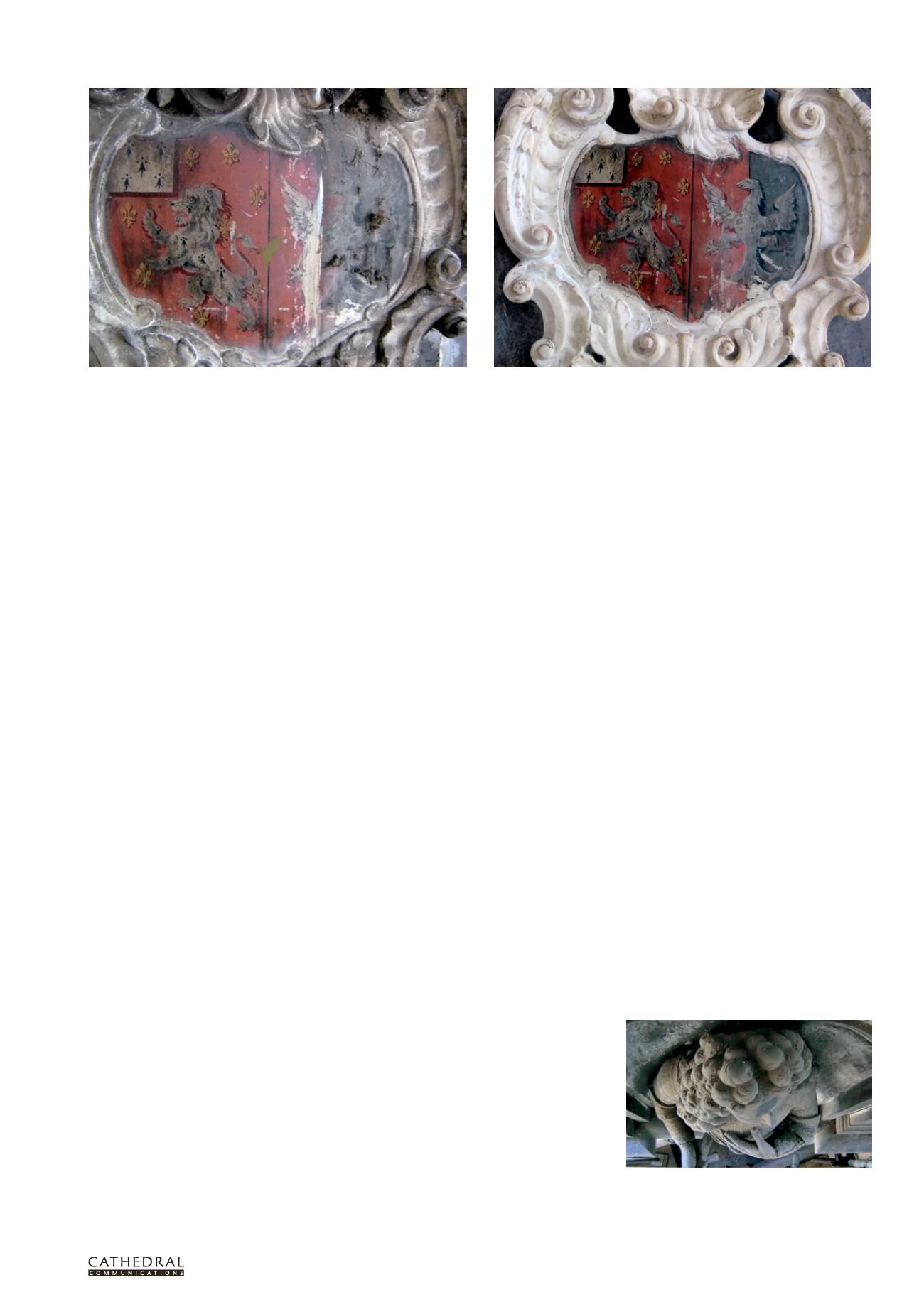

A finely decorated marble cartouche on a monument from the 1780s, before and after cleaning to remove dust, decorators paint and surface soiling. The monument had

been divided in two by a stud wall, hence the vertical paint marks. The solvents used included acetone, saliva and deionised water.

composition. Simpler memorials may rely on

just a handful of fixings. Clear indications

of corrosion can be seen in rust staining,

cracking, spalling and movement.

Surface soiling can be attributed primarily

to airborne dust and pollutants, degraded

coatings, staining through condensation or

water ingress, corrosion of metallic elements

and fixings, and human activity (such as

previous maintenance and restoration,

handling and graffiti).

Conservation of monuments may

therefore include partial or total rebuilding,

pinning and repair of breaks and losses,

re-pointing of failed and open joints, and

consolidation of decaying stonework or

decorative finishes.

Surface cleaning may therefore appear

to be low on the priority list for marble

monuments. However, it can enhance a

monument and allow a clearer reading of

both fine detail such as inscriptions and

the sculptural whole. There is also the

understandable desire to maintain a piece in

its best possible condition as a memorial to

an event or person and as a work of art in its

own right.

CLEANING ASSESSMENT

Before any cleaning is undertaken, careful

assessment and recording should be carried out.

As part of this initial process, an

assessment of the surfaces to be cleaned must

be made to get a better understanding of what

might be removed by cleaning and what may be

left. This must also take into consideration the

residues that could be left on the surface from

the cleaning process/material.