T W E N T Y F I R S T E D I T I O N

T H E B U I L D I N G C O N S E R VAT I O N D I R E C T O R Y 2 0 1 4

1 8 3

USEFUL INFORMATION

6

owned by a company registered in Panama,

and only the determined effort of local people

over many years persuaded Hastings Borough

Council, and ultimately the government, to

compulsorily purchase it for a community-led

trust to own and manage, following a major

restoration scheme which is being funded by

the Heritage Lottery Fund, the Architectural

Heritage Fund and many others.

A further, and growing, category of

historic buildings at risk is made up of those

where the use has been deemed redundant

by the owner, often a public body. This

might be a Carnegie library which the local

authority has decided to close and replace

with a brand new glass and steel ‘knowledge

hub’, with banks of PCs and not many books.

Or it could be a fire station, Victorian school,

town hall or swimming baths where the cost

of modernisation and adaptation is seen as

prohibitive. In the ideal scenario the public

body that owns the building has thought

through the ramifications of its decision to

close it and has an asset disposal strategy

in place, involving consultation with the

local community and even giving options to

community and voluntary sector groups to

take on the building for their own uses under

the asset transfer legislation. Sadly this is not

always the case and some public buildings

are simply abandoned while others are sold

on the open market, often to be turned into

expensive flats – far from the civic purpose for

which they were originally intended.

The Architectural Heritage Fund

(AHF) sees many cases where people come

together specifically because of concerns

about a prominent at risk building in their

local area. The AHF then suggests who else

they should talk to, always starting with the

local authority which, as outlined above,

has the powers to try to deal with owners

and can advise on planning issues. The

AHF’s other principal concerns, even at this

early stage, are whether an economically

viable use is likely to be identified for the

building and how the capital works may

be funded. AHF grant funding is geared

towards helping groups to ascertain the

answers to these vital questions, initially

through a short study called a viability

assessment. This should look at the building’s

structural issues, its current and potential

value, ownership and the willingness or

otherwise of the owner to negotiate on a

disposal, and, perhaps most importantly, the

potential use and long-term sustainability.

Of course the AHF is by no means the

only funding body that can help community

groups and others tackling historic buildings

at risk. The Funds for Historic Buildings

website (see further information) is a free

database listing all the major funding sources

and can be searched according to building

type, location and ownership, including

private ownership. Financial help for private

individuals, however, is scarce because most

charitable trusts will only fund other charities

or not-for-profit organisations.

The Heritage Lottery Fund (HLF) is by

far the largest supporter of projects tackling

buildings at risk, and in April 2013 it launched

the Heritage Enterprise scheme, specifically

aimed at encouraging communities to work

with developers to find commercially viable

solutions for large at risk buildings. At the

same time the HLF also introduced start-up

grants of up to £10,000 intended to help new

groups at the outset of their projects.

The Joint Committee of the National

Amenity Societies, which brings together the

likes of the Ancient Monuments Society, the

Victorian Society and the Twentieth Century

Society, runs another valuable website,

Heritage Help (see further information).

This contains short articles on some key

issues for owners of listed buildings,

campaigners and community groups and

also acts as a gateway, signposting users to

the main sources of information on topics

such as planning, maintenance and funding.

Buildingconservation.com also provides an

extensive list of free articles including many

on funding, legislation and the work of the

major heritage amenity societies.

So there is plenty of information and

advice available, but what is the picture like

when it comes to trying to tackle all those

buildings at risk on the various lists and

registers? First of all, it is worth remembering

that many are not ‘buildings’, as such,

but would be more accurately deemed

‘structures’. These might, for example, include

gateposts, walls, fountains, monuments and

consolidated ruins – none of them capable

of what the AHF would term ‘beneficial

reuse’. It is often challenging to persuade

an owner to invest in the maintenance of

such structures and hence they tend to

fall into disrepair and become at risk.

There are also buildings which have

been on these registers since they were

first compiled. These are the ones where

the problems are seemingly so intractable

that a solution seems virtually impossible.

However, in time and with the right

momentum behind them, the seemingly

impossible can become the next major

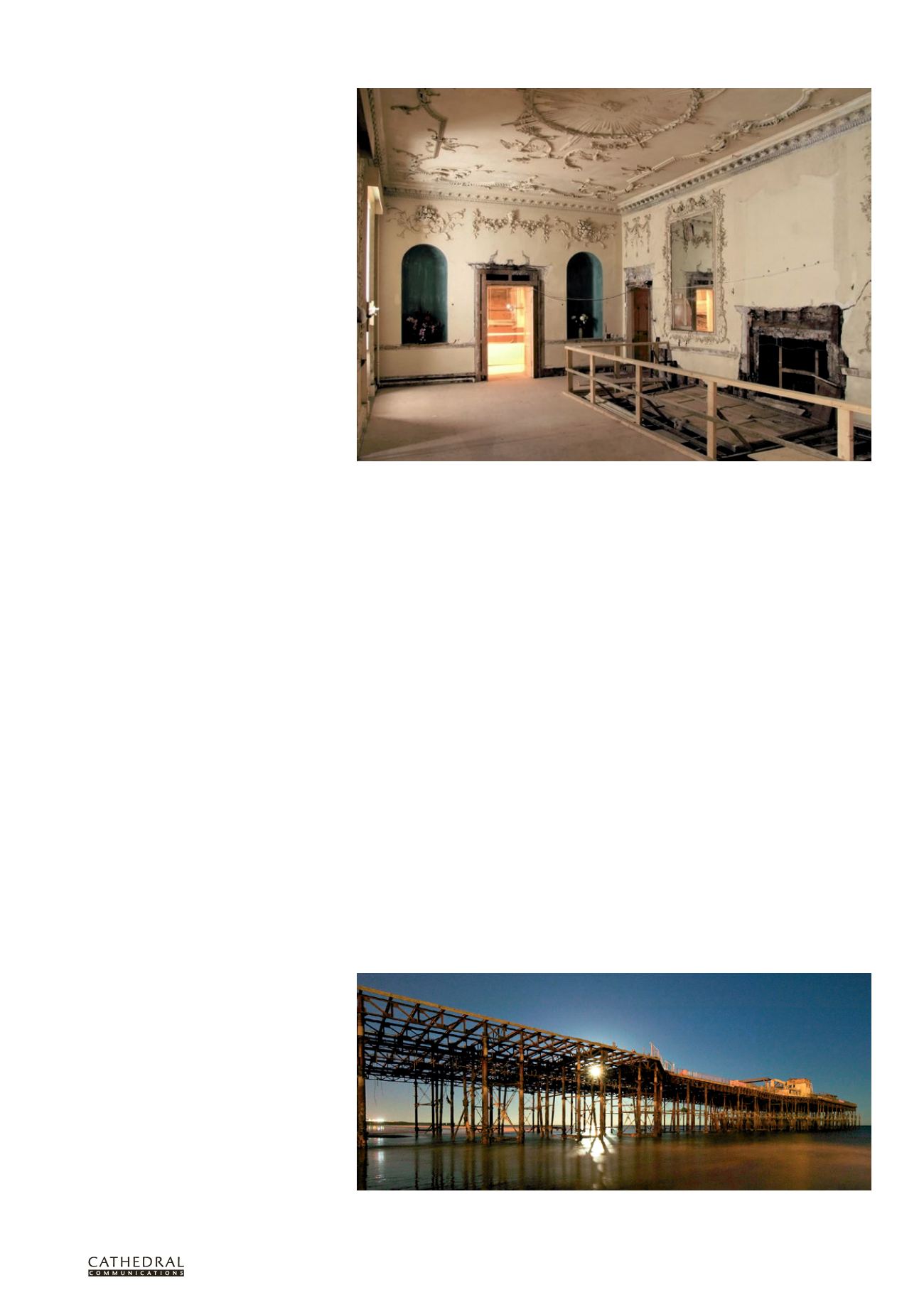

heritage project. Hastings Pier, particularly

after a disastrous fire in 2010, looked as if

it might be consigned to a similar fate to

Brighton’s West Pier, but the determination

of a local trust has ensured a potentially

happy ending to this particular heritage

story. Two other heritage causes célèbres,

Mavisbank House outside Edinburgh, and

Wentworth Woodhouse in South Yorkshire,

are now the subject of renewed schemes

for restoration and reuse, having also been

written off by many over the years.

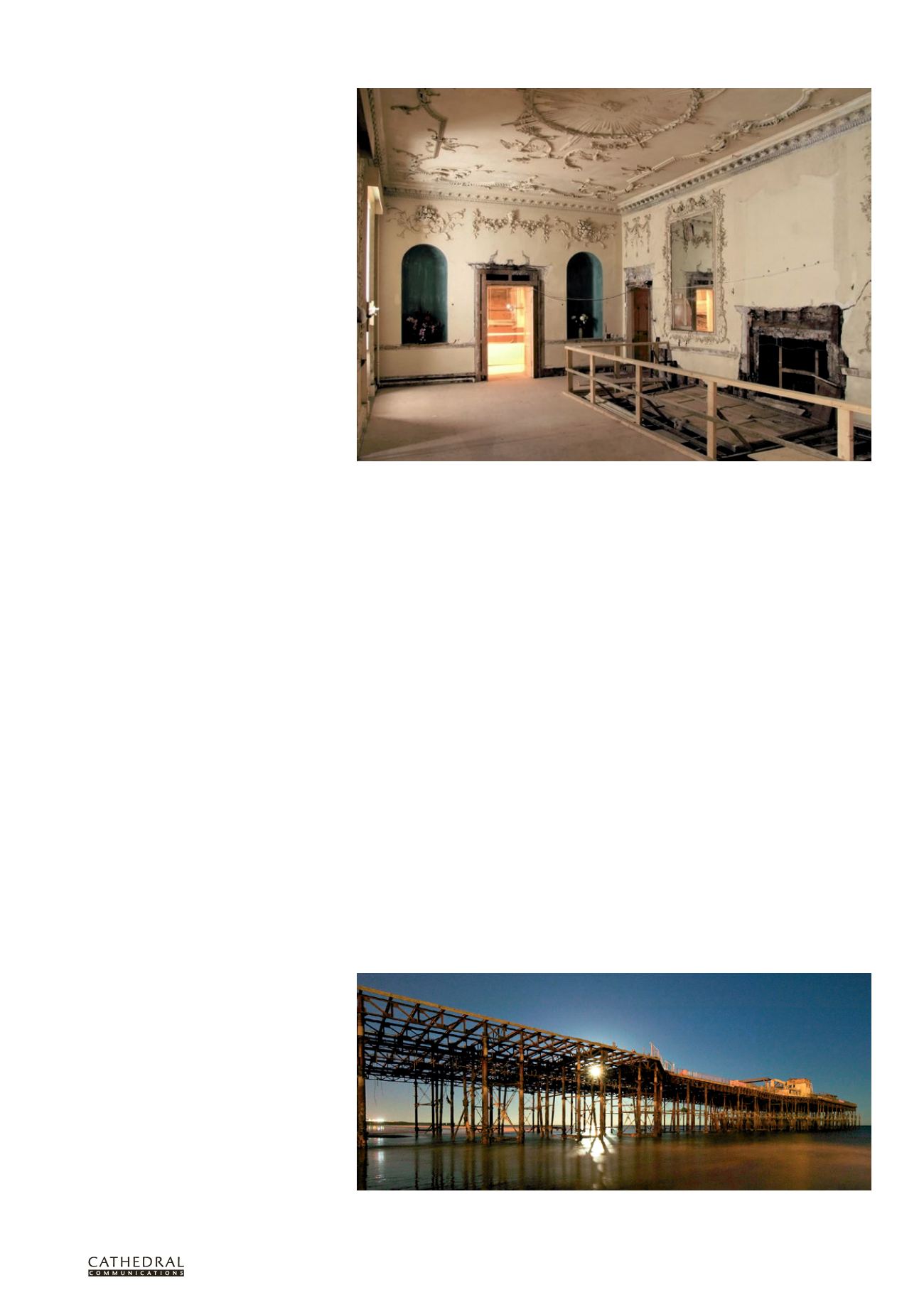

Poltimore House, near Exeter: despite setbacks including the discovery of asbestos, efforts continue to save this

extraordinary Grade II* building.

Hastings Pier following a devastating fire in October 2010