T W E N T Y F I R S T E D I T I O N

T H E B U I L D I N G C O N S E R VAT I O N D I R E C T O R Y 2 0 1 4

3

Foreword

T

he work and industry of the UK’s architectural conservation business

is admired all over the world, and in these pages we meet its great

names. Despite the growing awareness of the importance of historic

fabric and good repair, and the availability of skills, materials and resources

as illustrated in this Directory, buildings continue to fall under threat. Each

generation brings a new set of challenges, whether in the form of ideas such as

the post-war modernising aspirations that cut swathes through the middle of

our cities, or in the form of new projects and policies such as the HS2 railway

line and John Prescott’s destructive Pathfinder housing policy, that we are still

suffering the consequences of. New planning policy also brings new challenges

and, in England, one of the great tests of the new National Planning Policy

Framework has been the question of how to weigh the public benefits of a

scheme against any proposed harm to a listed building or conservation area.

Likewise, changing attitudes and fashions bring new possibilities for

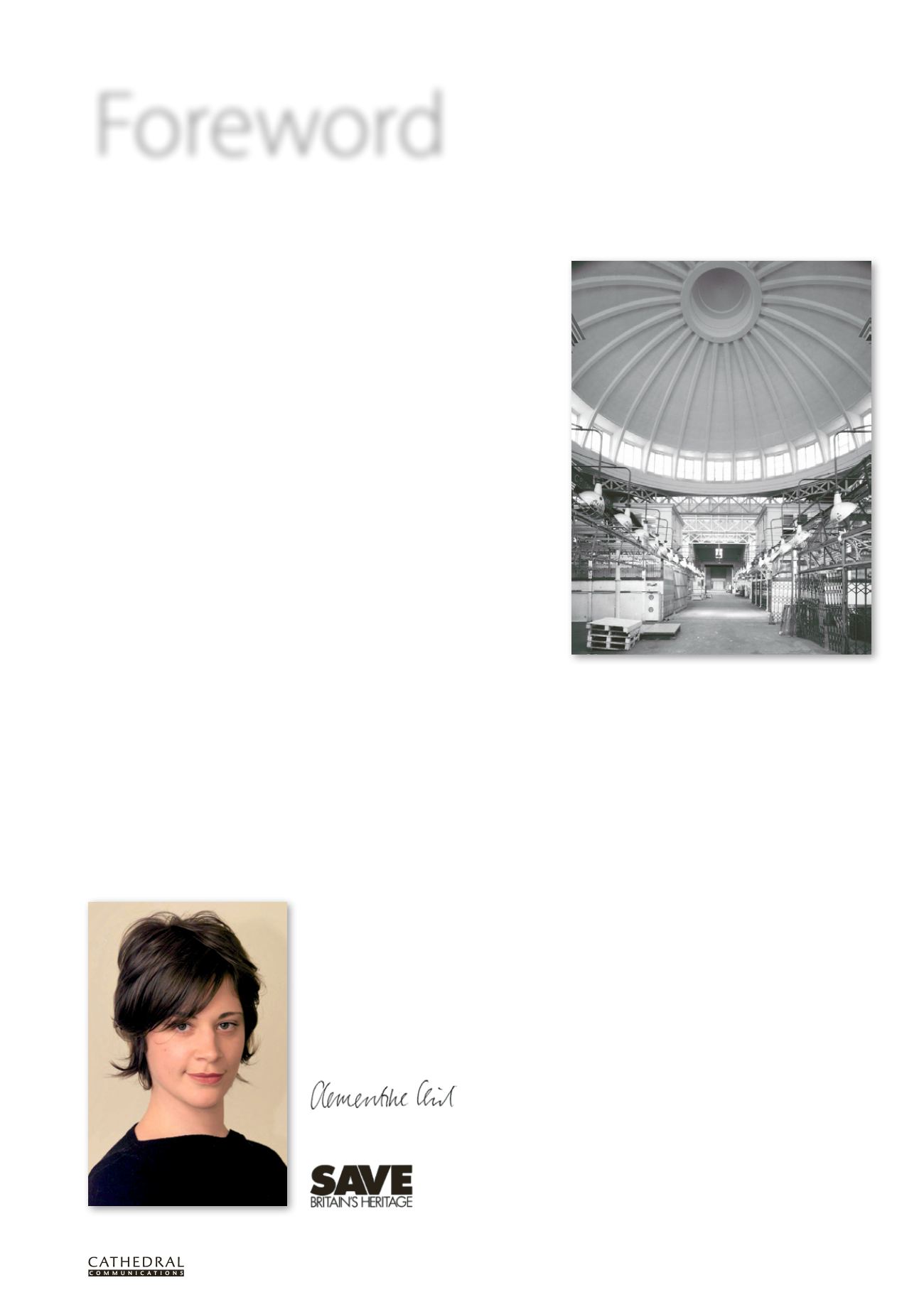

old buildings. One of SAVE’s most challenging campaigns is for Smithfield

General Market, a triumph of Victorian engineering and civic architecture

by former city surveyor Sir Horace Jones. Its magnificent market halls are

under threat of demolition, to be replaced with an anodyne office block. Only

three stretches of street frontage will remain. We had thought that the days

of facadism were behind us but this is one of the cruellest examples London

has seen for some time. Facadism not only knocks the heart out of a building,

it also leaves the remaining parts vulnerable: by losing the substance of the

building they were once a part of, the facades lose their meaning and anchor.

Perhaps the greatest danger of facadism is that heritage is seen as something

skin-deep.

The most successful examples of reuse are those where the right function meets the right historic building. One of the most

effective ways to ensure a positive outcome for a site is to draw up an alternative scheme accompanied by a strong image. Our

conservation-led proposal for Smithfield is for it to become a market once again, framed by shops, bars and cafés.

SAVE works with highly committed local campaigners who do whatever it takes to save a building, from researching its history

and engaging with the local authority, to organising petitions and fundraising to take the case to court if necessary. One of the

essential elements of a campaign is a strong press release that clearly makes the case for a building.

SAVE also occasionally oversees the restoration of buildings. One of these is Castle House

in Bridgwater, Somerset, which SAVE bought for £1 some 15 years ago. Built in the 1850s, the

‘concrete castle’ is a unique example of the early use of concrete. Due to the highly experimental

nature of the building, the urgent works demand meticulous planning and are quite risky. For

this reason we are working with leading conservation architects and structural engineers. Once

the funding is in place the building will be handed over to the local carnival charity, who will

use it as their headquarters.

There is a myriad of ways to save buildings, but the starting point is a passion for the site –

everything stems from that.

Clem Cecil

Director

Smithfield General Market, currently under threat of

demolition and the subject of an ongoing SAVE campaign

(Photo: SAVE Britain’s Heritage)