8

T H E B U I L D I N G C O N S E R VAT I O N D I R E C T O R Y 2 0 1 4

T W E N T Y F I R S T E D I T I O N

Heritage Training Group: this suggests that

over 100,000 people are already employed

within the sector to work on maintaining and

regenerating heritage buildings.

Within the wider education sector,

heritage sites and contexts provide rich

opportunities for learning, both inside and

outside the classroom, on a daily basis.

There is not a subject in the curriculum

which cannot use aspects of heritage in

demonstrating ideas or practical applications,

and schools benefit from diverse educational

resources provided by large and small

organisations on different types of site (from

understanding the structures of buildings

using physics to using the settings of historic

properties to generate creative artistic

responses or creative writing). Formal

education sees heritage at the heart of history,

art, archaeology, architecture and many other

subjects in secondary and tertiary education

environments, and subjects allied to heritage

remain popular with students. Academic

outputs (journal articles, reports, books, etc)

associated with heritage subjects continue

to grow year on year. The opportunities that

heritage provides as a glue which binds us

to locations in the world around us have far-

reaching value for aspiration, inspiration and

creativity as part of the wider cultural sphere.

One of the major values which is

accorded to the built heritage is through the

generation of tourism revenues from visits

to individual historic visitor attractions

and larger entities, characterised by their

historic buildings and streetscapes. Again,

there is a wealth of statistics and evaluation

of impacts from tourism, and yet there

continues to be a surprising amount of

distrust in the relationship between the

sectors. The heritage sector often considers

that tourism is exploitative and fails to

invest in the asset base, and that the tourism

experience and engagement with the visitor

is often undemanding, with visitors unable

to fully appreciate the cultural value of the

resource. Conversely, the tourism sector

considers the heritage sector to be far too

precious and purist about the management

and interpretation of its resource, and

un-businesslike in its operation.

This is perhaps taking some stereotypical

views to an extreme, but the tenor of these

views persists, despite heritage tourism being

one of the most successful growth markets

in the global economy, and Britain being

consistently in the top destination brands

for its cultural heritage offer. The heritage

tourism experience in Britain is generally

excellent, and soundly based on the important

work of the craftspeople and conservation

professionals who maintain the heritage fabric

of our buildings and places.

However, the industry cannot be

complacent: the visitor offer must compete in

a crowded and competitive market for leisure

time and spend from both global and domestic

consumers. The experience and service must

therefore be constantly enhanced, and therein

lies the tension between the areas. Regardless,

heritage, often through tourism-led initiatives

such as festivals or events, has clearly moved

into the realm of ‘lifestyle experience’, a fact

borne out by continued heritage society and

organisational membership, and the extension

of heritage as a theme into the branding of

consumer goods, foods and other products:

the appetite appears unabated.

This brings us back full circle to heritage

being very much a mainstream theme

within society and the way it behaves,

socially, politically and economically.

Wherever people are looking after and

engaging with the fabric of our heritage,

longer term outcomes and spin-off benefits

are emerging that the sector has really

only just begun to quantify, including

improvements in health and quality of life.

More could be said about developments

in technological approaches to heritage

preservation, maintenance and interpretation,

and the changing frameworks for managing

heritage as new models of management and

enterprise embed themselves in a fast-

changing economy, and as civil society takes

on more responsibility from what was once

expected as a public service function. More

too could be said of the divergent approaches

in policy between England and Scotland

towards heritage which are quickly emerging.

However, from the perspective of an academic

sitting in a university business school,

surveying the industry as a whole, the over-

riding impression is that the heritage industry

has already emerged as a clearly defined sector

with business complexity and a varied set of

value propositions that start with the fabric

and reach far beyond.

Further Information

Ecorys/Heritage Lottery Fund, The Economic

Impact of Maintaining and Repairing

Historic Buildings in England, HLF,

London, 2012

Heritage Counts

Heritage Lottery Fund, New Ideas Need Old

Buildings, HLF, London, 2013

Historic Environment Advisory Council for

Scotland, Report and Recommendations

on the Economic Impact of the Historic

Environment in Scotland, HEACS,

Edinburgh, 2009

National Heritage Training Group

Scotland’s Historic Environment Audit

UK Heritage Research Group

ukhrg.wordpress.com

IAN BAXTER

PhD FRSA FSA FSAScot

PIfA is the head of division of Tourism,

Heritage & Events at University Campus

Suffolk Business School. He has worked in

heritage management for 25 years, and

has contributed to the development of

the Heritage Counts and Scottish Heritage

Audit programmes as well as other policy

development initiatives in Scotland and

England. He is currently developing heritage

management as a strategic subject area for

UCS (see

).

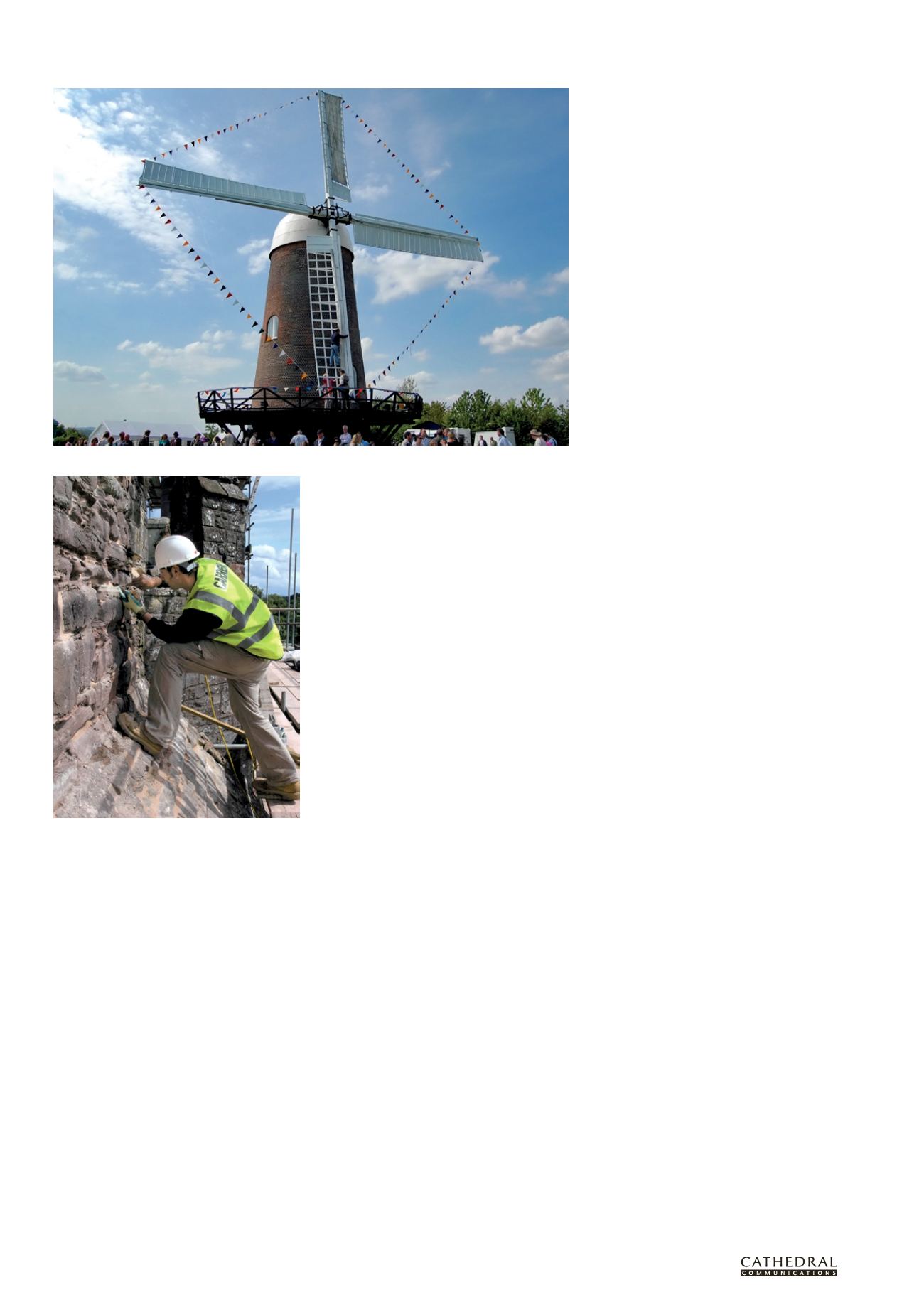

A Heritage Open Day at Wilton Windmill, Wiltshire (Photo: Susie Brew)

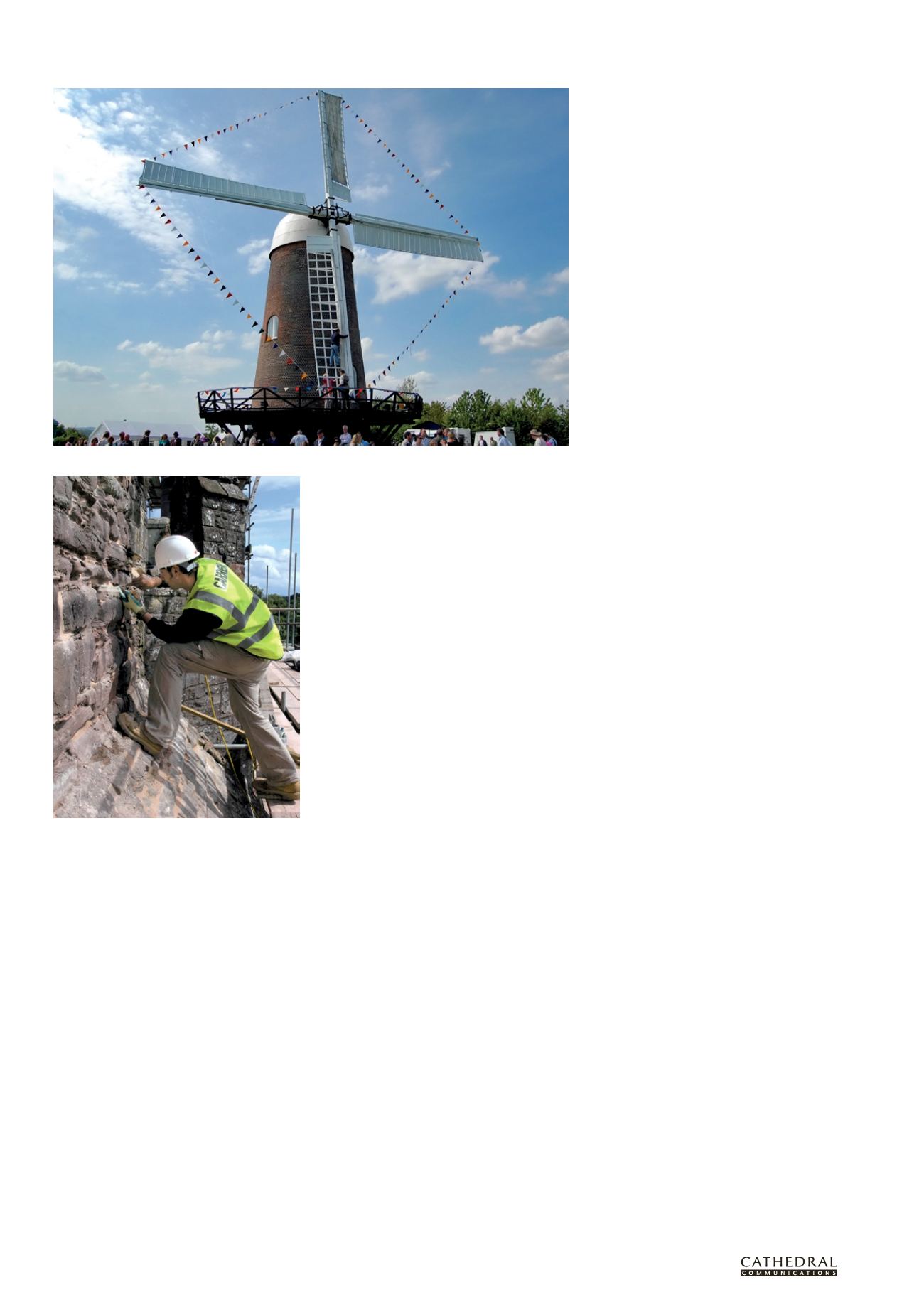

A conservator carries out masonry repairs at

Berkeley Castle, Gloucestershire