1 4

T H E B U I L D I N G C O N S E R VAT I O N D I R E C T O R Y 2 0 1 4

T W E N T Y F I R S T E D I T I O N

1

PROFESSIONAL SERVICES

staircases in a building may denote differences

in status between different areas and help

to identify the ways in which a building was

occupied and used. The means by which a

staircase is constructed may also demonstrate

historic methods of joinery and craftsmanship.

The fabric of the staircase not only

provides the tangible evidence upon which an

understanding of it is based but may also yield

further information through more in-depth

investigation. It is sometimes possible to date

a staircase by dendrochronological means but

more frequently the potential to learn more

lies in concealed historic fabric which may be

exposed through repair or alteration work.

Significance might also be derived

through association, for example if the

staircase is known to have been designed by

a particular architect or commissioned by

a well-known person or family. It may also

derive significance by virtue of its belonging to

a particular building.

Where a staircase is not bounded on both

sides by a wall, there is an obvious need to

provide a safety barrier. The incorporation

of a balustrade not only satisfies this basic

function but, frequently being located in the

main entrance or thoroughfare of a building,

also provides the perfect opportunity to use

design to impress. As such, there is often

substantial scope to ascribe significance on

account of a staircase’s aesthetic value.

COMMON DEFECTS, MANAGEMENT

AND MAINTENANCE

Most defects are likely to arise through

general wear and tear, accidental damage,

inadequate control of damp, repeated

exposure to fluctuations in temperature and

relative humidity, or inappropriate repairs.

Many of these risks can be minimised

and their consequences delayed through

appropriate management and maintenance,

which will prolong the structural safety of

a staircase and safeguard sensitive historic

fabric for as long as possible.

A degree of wear and tear is usually

inevitable but the volume of traffic can be

reduced in some buildings, particularly those

with more than one staircase or where there

is the potential to add another one in a less

historically sensitive part of the building. If

traffic cannot be reduced, other protective

measures might prove viable, such as the use

of a carpet to form a protective layer. However,

care must be taken when choosing and

fitting a carpet to avoid causing harm to the

underlying structure. An appropriate cleaning

regime will also serve to prevent the build-up

of harmful agents of decay.

Excessive moisture and poor ventilation

can facilitate fungal decay (wet or dry rot)

or provide ideal conditions for wood-boring

beetles. Particularly susceptible areas include

those where a staircase borders an outer wall

or a void over a cellar. Good general building

maintenance will minimise the risks but some

issues, such as moisture in cellars, remain

notoriously problematic.

Frequent fluctuations in temperature

and relative humidity can exacerbate

problems with damp but also lead to problems

associated with the drying-out of timber,

including loosening of components, splitting

and cracking. This is most likely to be a

problem where a staircase is close to a main

entrance, where the repeated opening and

closing of doors to the exterior, coupled with

modern central heating is likely to cause

frequent fluctuations. The general aim here

is to maintain a temperature and relative

humidity within a more stable range, which

might be achieved by lowering heating

controls, or perhaps employing humidifiers or

dehumidifiers.

Prior to the late 16th century, most

staircases were composed of solid timber

or stone treads. Medieval timber staircases

characteristically had triangular-section

treads but these are now rare and the vast

majority of surviving timber staircases are of

composite form, with treads and risers formed

of individual pieces of timber. These are

generally secured by a series of timber wedges

which serve to tighten up the individual

components. Sometimes these become loose

through general wear and tear, or through

fluctuations in atmospheric conditions.

However, if the underside of the stair is readily

accessible it is relatively easy to tighten-up the

joints by tapping the wedges back into place.

REINFORCEMENT, REPAIR AND RENEWAL

Even with appropriate cleaning and

maintenance, a staircase which is in regular

use will eventually need some strengthening

or repair work. This is particularly important

where the safety of the stair is compromised,

for example where treads or nosings are

unstable or excessively worn, or where

balusters or handrails are damaged.

In accordance with English Heritage

guidance, any repair should involve minimum

intervention. This will ensure maximum

retention of historic fabric but should also

reduce the potential for any conflict with

building regulations, and in the case of listed

buildings may avoid the need to obtain listed

building consent.

In some cases the existing structure can

be reinforced with no loss of historic fabric.

For example, unstable treads can be reinforced

through the addition of secondary support.

Where possible, any reinforcement should

be carried out from the underside of the

stair: this might easily be achieved where the

structure is exposed, for example in an under-

stairs cupboard, or over a cellar access, but in

some cases might require removal of discrete

areas of a historic lath and plaster finish.

In such cases, the area of plaster removed

should be kept to a minimum and should be

reinstated in a like-for-like manner. If the

underside of a stair is intended to be seen, the

sweep of the treads forms an essential element

of its design aesthetic so secondary support to

the underside is unlikely to be appropriate.

Some repairs can be undertaken in situ,

for example the gluing of a split baluster or

damaged nosing, while other repairs might

require the fabrication of new pieces, such as

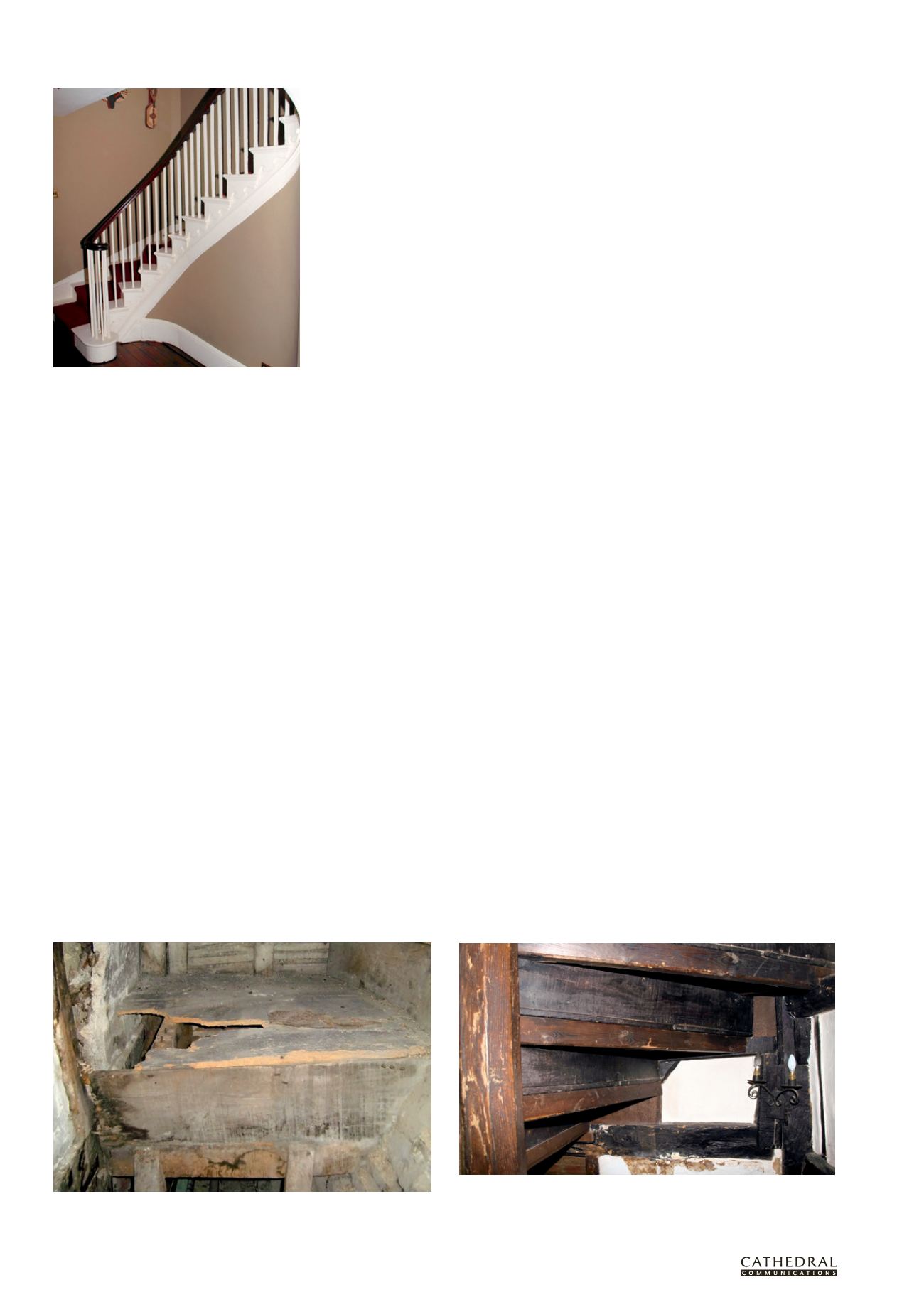

This simple but elegant late 18th-century balustrade

provides a pleasing visual effect. (All photos:

Archaeology South-East)

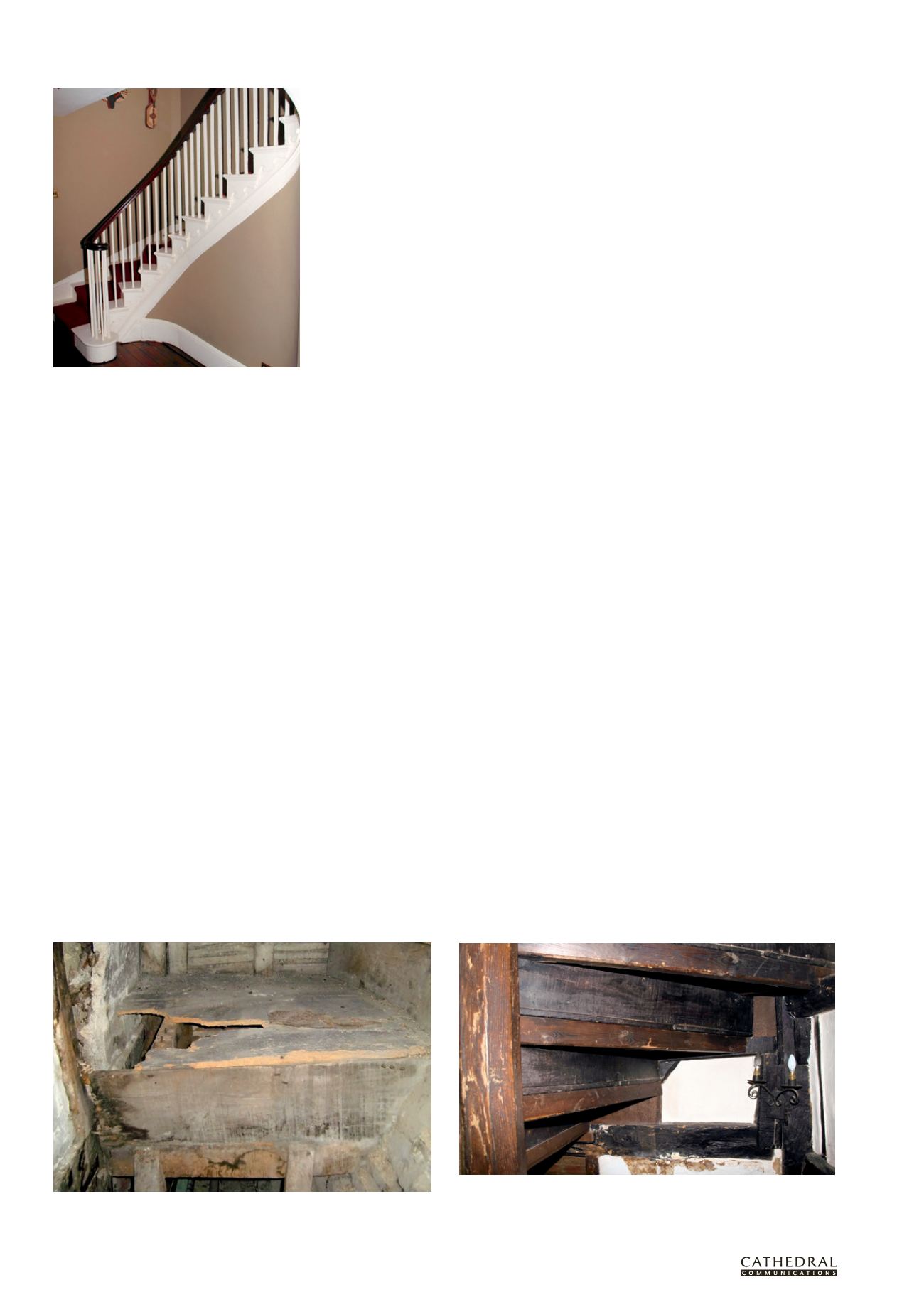

A decayed stair tread caused by wood-boring beetle infestation

The secondary supports introduced beneath this existing staircase structure have

not resulted in any loss of historic material.