T W E N T Y F I R S T E D I T I O N

T H E B U I L D I N G C O N S E R VAT I O N D I R E C T O R Y 2 0 1 4

1 5

1

PROFESSIONAL SERVICES

potential to severely compromise the aesthetic

of a stair or result in the unregulated loss of

historic fabric which, in the worst cases, might

extend to total loss.

NEGOTIATING THE ISSUES

Anyone involved in the conservation of

historic buildings will recognise that it is

not always easy to find a path through the

minefield of competing issues that commonly

arise. However, being in possession of good

information at an early stage will help to

guide the process and allow the impact of any

proposals to be evaluated so that the building

or component will hopefully remain in use

and retain those qualities that make it special.

Recommended Reading

C Brereton, The Repair of Historic Buildings:

Advice on Principles and Methods, English

Heritage, Swindon, 2012

Cadw, Conservation Principles for the

Sustainable Management of the Historic

Environment in Wales, Cadw, Cardiff, 2011

JWP Campbell and M Tutton (eds), Staircases:

History, Repair and Conservation,

Routledge, London, (forthcoming)

English Heritage, Conservation Principles:

Policies and Guidance for the Sustainable

Management of the Historic Environment,

EH, London, 2008

A Jackson and D Day, Period House, Harper

Collins/English Heritage, London, 2005

M Jenkins, Timber Staircases, Historic

Scotland Inform Guide, Edinburgh, 2010

D Urquhart, Conversion of Traditional

Buildings: Application of the Building

Standards, (Guide for Practitioners 6),

Historic Scotland, Edinburgh, 2007

AMYWILLIAMSON

BA is senior historic

buildings archaeologist at Archaeology

South-East

), part of the Centre

for Applied Archaeology at University

College London. Her work involves

recording, assessing and advising on a wide

variety of historic buildings ranging from

medieval vernacular buildings to 20th-

century concrete structures, for a wide

variety of public and private clients.

a new baluster or section of handrail, or the

insertion of replacement treads and risers. The

composite nature of the construction of most

staircases means that it should be possible to

replace individual treads and risers without

undue disturbance of surrounding fabric. It

should also be possible to re-fix the triangular

blocks that help to hold the treads and risers in

place. Where new timber is to be introduced,

fully seasoned timber should always be used, as

this will minimise the potential for shrinkage

and warping which might compromise the

effectiveness and longevity of any repairs.

Where components important to the

aesthetic of a staircase need to be replaced, it

is important that these conform to the existing

ones so as not to compromise the overall

effect, for example by interrupting the pleasing

repetition of a well-designed balustrade.

If any required repair or renewal works

are likely to involve substantial loss of

material, or are likely to radically alter the

appearance of the staircase, the conservation

officer may require that a written,

photographic and possibly drawn record be

made of it prior to work commencing. If works

have the potential to reveal previously unseen

historic fabric, then it might be appropriate

to use the opportunity to carry out further

analysis and/or recording work.

BUILDING REGULATIONS

Issues concerning building regulations

typically arise when there are proposals under

way to make changes to a building, particularly

when these involve a change in use.

Compliance with building regulations is often

a thorny subject when dealing with historic

buildings. Because most historic buildings

were constructed by local craftspeople before

the introduction of standardised regulations,

changes that might be desirable in terms of

modern safety standards are often difficult to

achieve without compromising those parts of

a historic building or component that make it

significant in heritage terms.

Building regulations dictate minimum

standards for new work, which includes

alterations to existing fabric. In England and

Wales Approved Document K: Protection

from falling, collision and impact outlines the

requirements for stairs, including pitch, step

construction, headroom, width and length of

flights, and requirements for the guarding of

stairs, including the form and height of any

guarding. The equivalent Scottish building

standards are set out in Technical Handbook –

Domestic, Section 4 Safety (2013).

Simple vernacular staircases are among

the most vulnerable. They often lack a

handrail, tend to rise very steeply either as

a straight flight, or incorporating half or

three-quarter turns, and often have restricted

headroom. Because of these traits owners of

historic buildings sometimes seek to alter

this type of staircase – a proposal that would

probably be encouraged by the building

control officer but would cause dismay among

many conservation professionals.

There is some scope for the relaxation

of the requirements of building regulations

for historic buildings where doing so can be

shown to be necessary in order to preserve

the architectural and historical integrity of

the building. However, the extent to which

the requirements will be relaxed depends

on how the staircase is used. For example,

if it is in a workplace or publicly accessible

building, the potential risks might be deemed

greater than in a domestic dwelling. In cases

where there are likely to be conflicting issues,

early discussions involving both the building

control officer and conservation officer can be

particularly helpful.

Unfortunately, the many historic

staircases in undesignated buildings do not

generally enjoy the same level of protection

as their listed counterparts so alteration

works will usually be subject to the full force

of the regulations. In addition, health and

safety legislation applies to all buildings,

including listed ones, placing on the occupiers

of a property ‘a duty to take such care as

is reasonable in all the circumstances to

see that visitors will be reasonably safe for

the purposes for which they are invited

or permitted to be there’. In cases where

alterations cannot be avoided, modern safety

measures such as additional handrails,

contrasting nosings and firebreaks have the

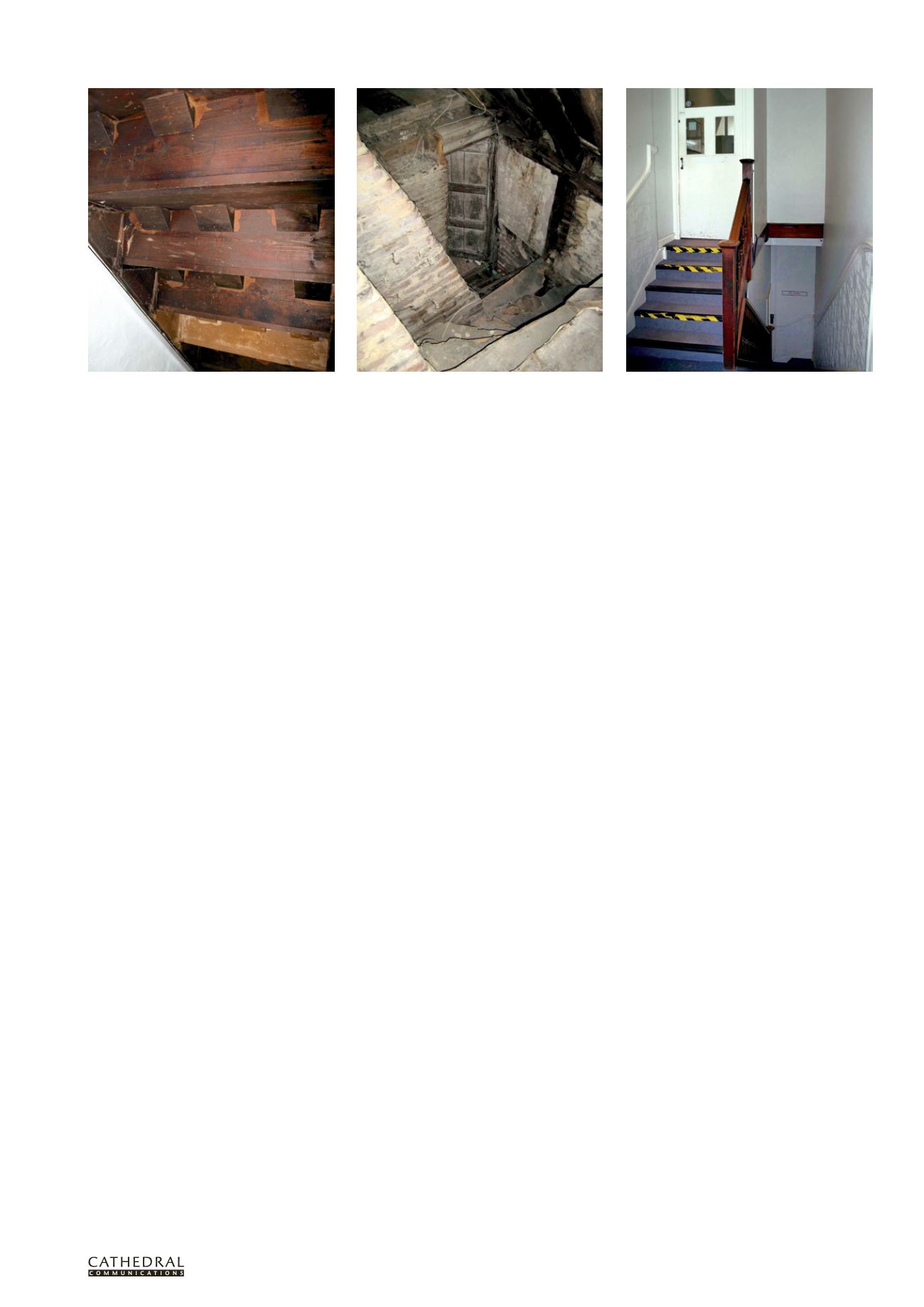

The replacement of individual components has been

achieved here with little or no disruption to the

surrounding fabric (note the re-fixed triangular wedges).

A typical 18th-century attic staircase, tucked into the

space afforded by the narrowing of a chimney stack: it is

steeply pitched with winding treads and has no handrail

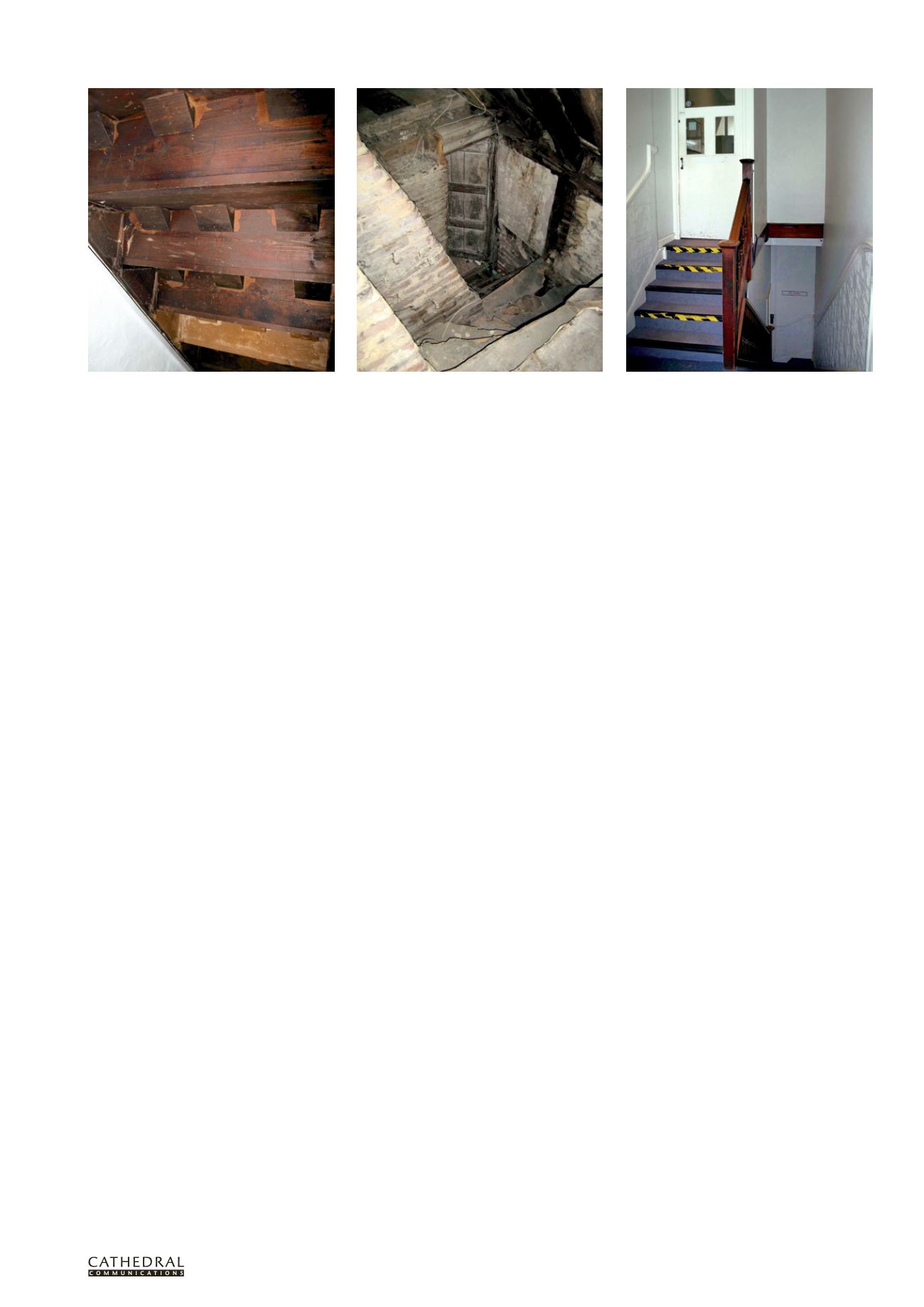

The aesthetic of this staircase (c1900) has been diminished

by the introduction of modern safety measures,

including the fire-walls and contrasting nosings.