T W E N T Y F I R S T E D I T I O N

T H E B U I L D I N G C O N S E R VAT I O N D I R E C T O R Y 2 0 1 4

5 9

2

BUILDING CONTRACTORS

CRIMINAL DAMAGE

JONATHAN TAYLOR

I

N 2011

a survey commissioned by English

Heritage found that 19 per cent of all listed

buildings in England were affected by

criminal damage in that year alone (see www.

english-heritage.org.uk/heritagecrime). The

‘heritage crimes’ recorded ranged from graffiti

and unauthorised alterations to the theft of

metal roof coverings and arson, and in almost

half the cases the damage was substantial.

Although the study was limited to

England, criminal damage to historic

buildings is common throughout the UK.

Most at risk are buildings which are known

to be unoccupied at night, such as churches

and building sites where historic buildings are

vacated and scaffolded, and the biggest single

threat is metal theft.

CAUSE AND EFFECT

Damage to historic buildings is often

incidental and a consequence of ignorance.

Damage by owners and developers acting

without listed building consent is usually made

in ignorance of the law or of the importance

of having specialist advice – or both. In some

cases it is simply that the owner or the building

contractor is unaware that every element of a

listed building is protected by law, and that it

is a criminal offence to carry out most work

without listed building consent. In other cases

the owner or contractor may consider that

the works are relatively minor, and that listed

building consent is simply unnecessary red

tape which will serve only to delay work.

Most owners and contractors do not set

out to intentionally harm the building they are

responsible for, but without the scrutiny of the

conservation officer mistakes happen.

Ignorance of the consequences also

contributes to the harm caused through

graffiti and some acts of vandalism, as

outlined by Lucy Branch on page 93. Historic

buildings and monuments are a finite

resource, and over time the cumulative impact

of repeated cleaning, repair, damage and loss

can be devastating.

High rates of theft, graffiti and arson

are often prevalent in specific urban areas,

reflecting a wider context of social problems.

The visible impact on the environment can

discourage investment in the buildings

of that area, compounding the problem.

Without prompt action by key stakeholders

and the local authority, historic buildings and

residents can be caught in a vicious cycle of

urban decline.

The high price paid for some recycled

materials and architectural salvage has

encouraged thefts from historic buildings.

In recent years lead roofs have been the

most common targets for thieves, fuelled

by soaring demand for scrap metal, but

other items are often stolen too, including

decorative features such as fireplaces

and sculptures. Even clay tiles have been

stripped from the roofs of remote farm

buildings, and scaffolds can provide easy

access to a wide variety of equipment and

materials in unoccupied buildings.

According to the research commissioned

by English Heritage, one in seven religious

buildings had been affected by lead theft. Not

only roofs are affected, but also gutters and

downpipes. Whether the material is plain and

modern or hundreds of years old and of great

architectural and historic interest, it all ends

up in the melting pot. When hidden flashings

and parapet gutters are stolen, often the first

sign of the theft is a leaking roof following a

storm, and the consequent water ingress adds

to the damage already caused.

All burglaries from historic buildings

contribute damage to historic fabric, and in

the most appalling cases, burglars have been

known to set fire to the building in order to

hide evidence.

Fabric and components introduced to

replace those which have been damaged or

lost are of course new, not historic. Repairs

and replacements will help to secure the

integrity of the building or monument, and

may be beautiful in their own right, but the

connection with the past is diminished.

PREVENTION

All historic buildings should have a risk

assessment carried out to identify which

elements are most likely to be the targets of

vandalism or theft, when they are most at risk,

and how access is likely to be gained. In most

cases this is not complex and may be carried

out by either the owner or the professional

with the advice of the police, but in the more

complex and most important cases it may be

necessary to bring in a security consultant

with specialist expertise. Specific risk

assessments should also be carried out when

major works are undertaken or the building is

to be vacated for a long period.

Key areas to be considered include:

Perimeter protection

– ideally, it should be

possible to exclude all vehicular access when

necessary, to prevent the removal of large

objects: notices at the principal access points

can also help to deter intruders by advising

them of the deterrence measures in place

(such as the security marking systems used),

and by asking visitors to report any suspicious

activity to the police

Surveillance

– intruders and others

should feel watched in all areas immediately

around the building: consider security lighting

(which need not be ugly) and visible indicators

of surveillance such as cameras, and lights

inside the building

Access to tool stores

etc – implements

which might be useful to a burglar, arsonist or

other miscreant must be well secured

Building envelope protection

– all likely

access points should be identified, secured

and, where possible, alarmed, including doors,

windows and their related access routes such

as walls, drainpipes and roofs (anti-climb

paint may be used above two metres with

appropriate warning notices)

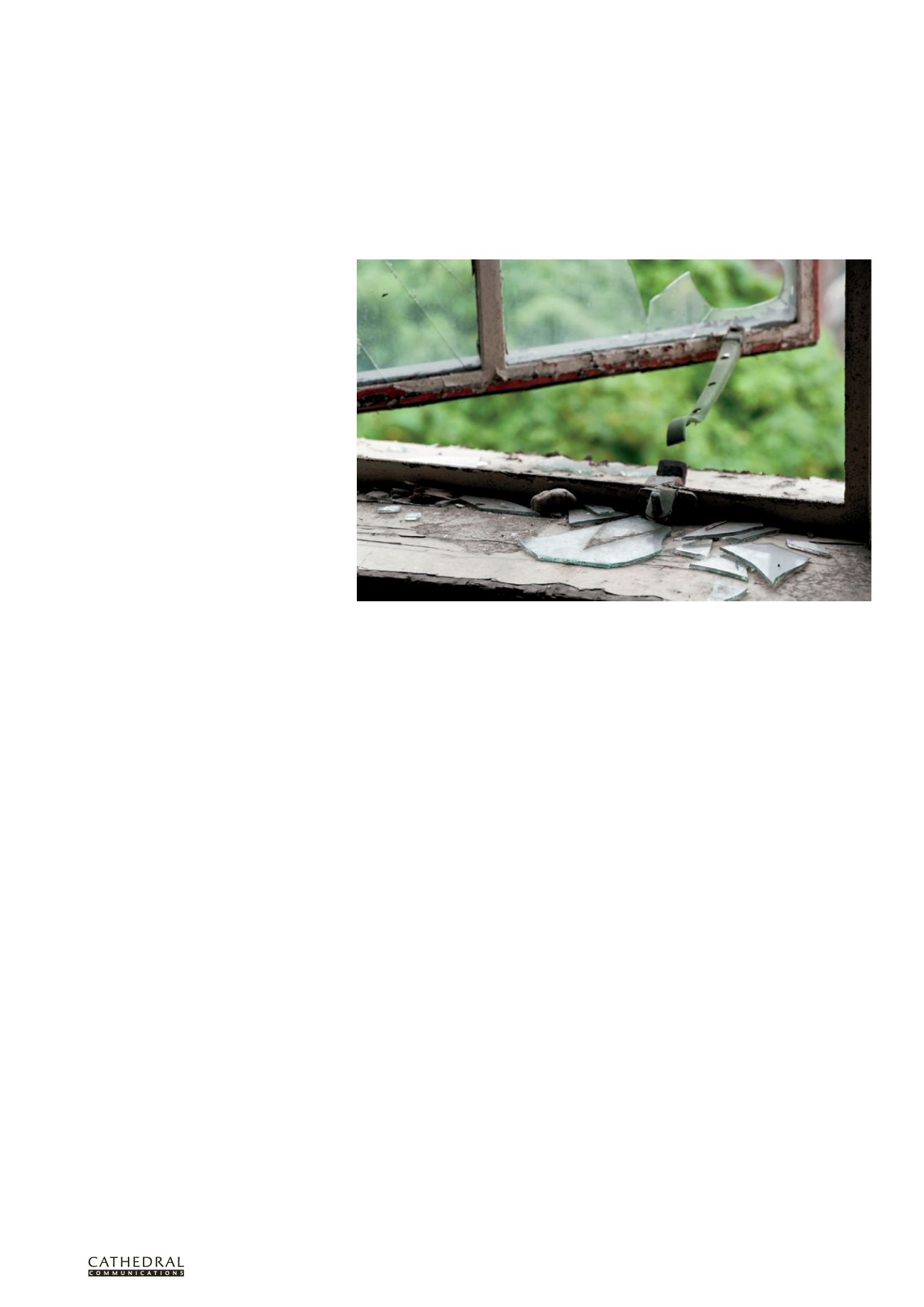

(Photo ©iStock.com/zmeel)