T W E N T Y F I R S T E D I T I O N

T H E B U I L D I N G C O N S E R VAT I O N D I R E C T O R Y 2 0 1 4

9 3

3.2

STRUCTURE & FABRIC :

MASONRY

‘I WOZ ERE’

REPAIRING PUBLIC MONUMENTS AND SCULPTURE

LUCY BRANCH

T

HE VANDALISM

and theft of monuments

has never been more topical. In July

this year the BBC reported nine news

stories on the vandalism of heritage compared

to none in the whole of 2008. The launch of

initiatives such as the Alliance to Reduce

Crime Against Heritage, the Heritage Crime

Programme and the Association of Chief

Police Officers’ Metal Theft Working Group,

suggests that the conservation community

is concerned that the stories that hit the

headlines are just the tip of the iceberg. There

is a strong sense that this is a critical time

and that steps must be taken to prevent the

problem escalating further.

Because so few acts of vandalism or theft

result in prosecution, few firm statistics exist

and it is hard to track annual changes in the

nature and frequency of this type of crime.

However, press coverage over the last decade

indicates that the most high profile statues

have regularly attracted abuse while theft

within this group has also risen.

According to the Public Monuments and

Sculpture Association (PMSA), although the

theft of public sculpture has certainly become

more appealing to criminals since the price of

copper alloys increased, it is by no means clear

that scrap value is the only reason for this

worrying trend.

There is a common assumption that the

motivation for all the theft and vandalism

associated with our heritage can be summed

up in two words: money and ignorance.

Taking the trouble to consider carefully why

an object has been vandalised makes for

better conservation decisions, and sometimes

reveals a slightly less bleak picture of the

human race, which must be good for any

conservator’s soul.

Iconoclasm

The destruction of cultural

property for political or religious ideals. This

type of vandalism is probably as old as art

itself. A current exhibition at Tate Britain, ‘Art

under Attack: Histories of British Iconoclasm’,

explores such attacks on art in Britain since

the 16th century. The objects on display

demonstrate that this type of vandalism is not

a modern phenomenon.

In March 2011, anti-cuts protests took

place following a TUC rally which left

Trafalgar Square and other parts of central

London in a mess. The damage cost tens of

thousands of pounds to repair according

to a council official. Protesters daubed red

and black paint on monuments and on the

Olympic countdown clock in Trafalgar Square.

Celebration

Sometimes out of sheer

exuberance, people feel the need to ‘decorate’

a sculpture or climb to its highest point. This

may take the form of applying lipstick or

placing a jaunty traffic cone on a monument’s

head. Particularly during sporting events and

even elections, the desire to climb sculptures

seems to be overwhelming for some.

Riots may be hard to predict but we can

anticipate many of the sporting events that

will excite the nation and often have advance

warning about demonstrations and protests.

Temporary hoarding of monuments that

have a history of being targeted can help to

prevent further serious abuse. Although not

particularly aesthetically pleasing, there are

examples of innovation in this area such as

protecting London’s Shaftesbury Memorial

from New Year’s Eve revellers by enclosing it

in a protective plastic dome which was styled

to imitate a snow globe.

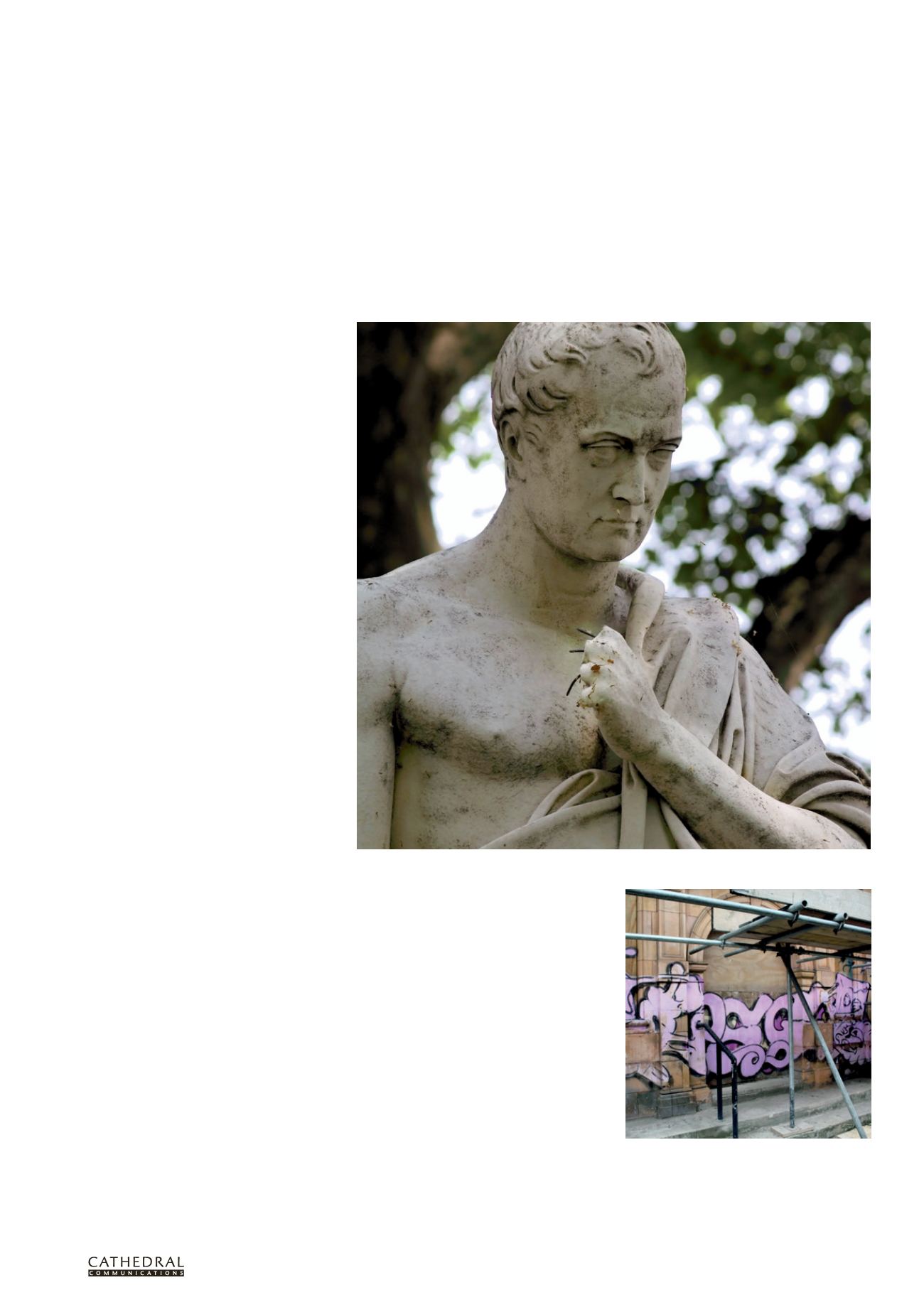

Statue of William Huskisson in Pimlico Gardens, London, which was repeatedly targeted by vandals

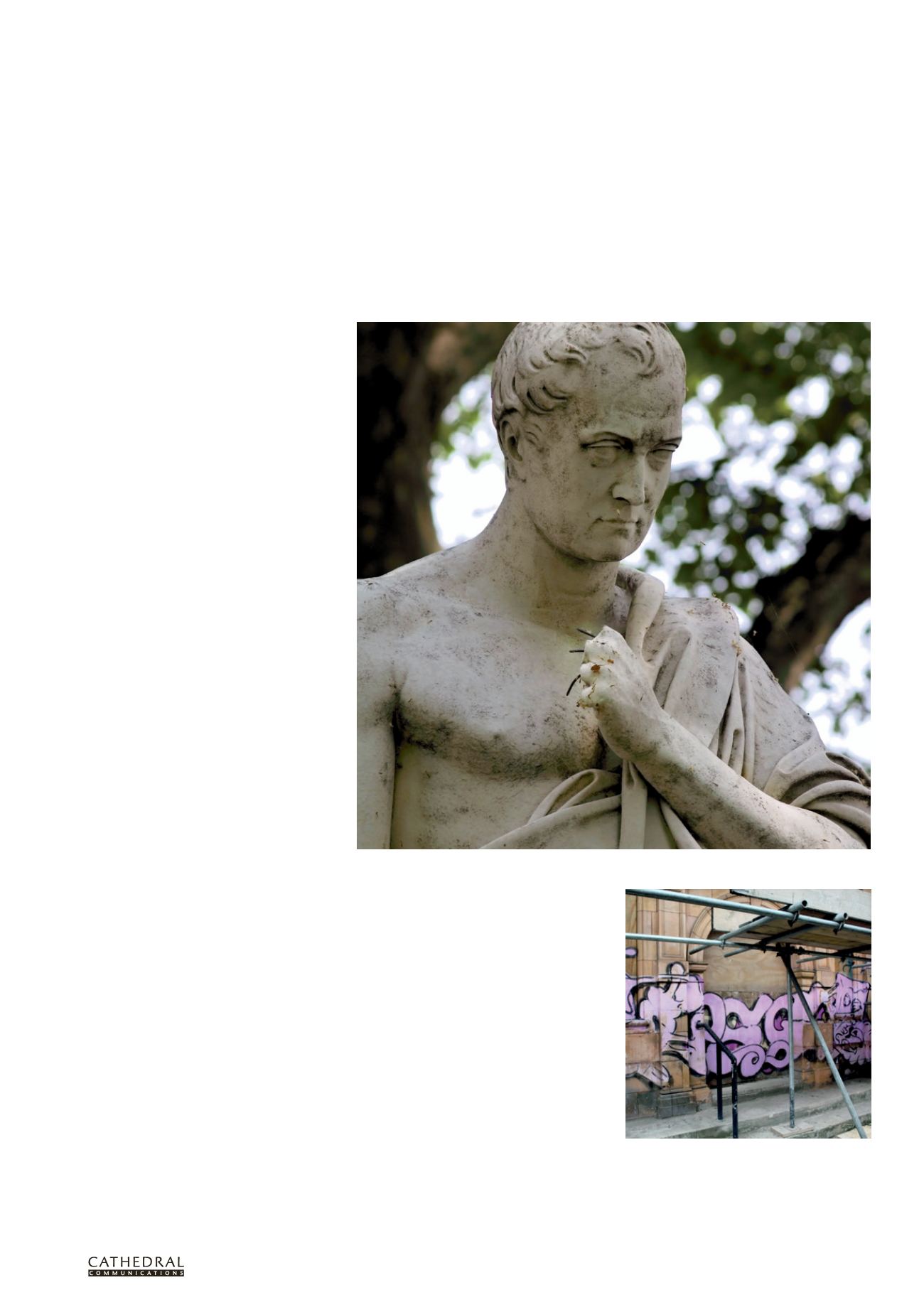

The swift removal of graffiti tags undermines the

tagger’s objective of self-advertisement while also

reducing the likelihood of damage being caused by

the paint remaining in contact with the surface over

a period of time. (Photo: Restorative Techniques)