9 4

T H E B U I L D I N G C O N S E R VAT I O N D I R E C T O R Y 2 0 1 4

T W E N T Y F I R S T E D I T I O N

3.2

STRUCTURE & FABRIC :

MASONRY

Tagging

The addition of a unique

signature or ‘tag’ to an object is about being

seen. Some types of tagging reportedly relate

to gangs marking territory.

In the case of repeated attacks,

encouraging the client towards a programme

of swift tag-removal quickly undermines those

people who have chosen to target a particular

monument. The purpose of being seen is

futile if the tag is removed within hours of

its creation. Swift removal also reduces the

likelihood of damage being caused by the

paint remaining in contact with the surface

over a period of time.

Attention seeking

This kind of vandalism

can often result in breakages. Commonly,

sculptures are climbed and the weaker points

suffer damage. The statue at the top of the

Shaftesbury Memorial (popularly known as

Eros although it actually depicts his brother

Anteros) is a common target for people who

want to get noticed. Each year, there is usually

at least one ascent resulting in some kind

of damage. The delicate bowstring is often

snapped and sometimes the bow is bent out of

alignment and requires careful manipulation

under moderate heat to return it to its

intended shape.

Theft

It is not just the successful theft

of metal statues for scrap that results in the

loss of historic fabric. The thieves are often

opportunists who lack suitable tools. Sadly

their efforts can still cause extensive damage.

Encouraging clients to have their statues

and monuments checked regularly is one of

the best ways of preventing theft. If fixings

are loose or broken, or joints are exposed

allowing tools to be forced in behind the

object, theft is much easier and therefore

more likely.

Vendettas

Bizarre as it may sound, some

statues have their own enemies. Vandalism

in such cases is targeted and undertaken

repeatedly. This type of vandalism can take

the form of graffiti or less superficial damage.

A white marble monument to the

Georgian statesman William Huskisson

in Pimlico Gardens, London suffered

repeat attacks over a number of years

during which one of the figure’s hands

was smashed repeatedly. This type of

vandalism was also suffered by the dolphins

on Shakespeare’s Memorial in Leicester

Square. One approach to conservation in this

context is to delay the proper conservation

treatment until the perpetrator is caught

or eventually loses interest and to make

a temporary repair in the meantime.

In the case of the Huskisson monument,

the ultimate goal was to reinstate the fingers

in the high-grade marble that the statue

was made from. In the shorter term, the

aim was to remake the fingers in a medium

that was very close in colour and texture to

the original but by a means that was easily

reproducible if they were smashed again.

It was important to make these temporary

fingers in a material that was soft enough

to break easily when hit so that the existing

marble was put under the least possible strain

when under attack.

Making a pattern of the fingers and

taking a mould served this situation well.

Casting the fingers in a marble dust mix

meant that the fingers were fragile enough to

almost disintegrate when struck and cost very

little to replace. Eventually, the fingers were

re-carved and reattached to the original stubs

with small non-ferrous pins.

Random attacks

This type of damage

can be the most difficult to deal with. Quite

often, the decision to vandalise has been

entirely unpremeditated and so a person uses

anything they might have on them such as a

penknife or key.

Social problems

Statues often provide a

focal point for people to gather around and

in some areas statues seem to be a magnet

for people with social problems such as

alcoholism, drug abuse or mental health

issues. Vandalism in this category is often

prolific and may take a variety of forms, from

graffiti to arson.

Encouraging custodians of sculpture

to understand the importance of good

housekeeping in the surrounding area is

a good preventive measure. Graffiti and

antisocial behaviour very often occur when

there is a neglected site, weeds, damaged

stones and other graffiti on buildings. If areas

look uncared for, an assumption can be made

that vandalism in that area is acceptable.

REMOVING GRAFFITI

Usually, the first method trialled to remove

graffiti from stone is steam, soap and a nylon

brush. This is often successful, although

ghosting can be left behind. This is the

result of the intense pigment density of the

paint which has penetrated the stone. When

this type of ghosting occurs, repetition and

patience can yield a positive result in time.

However, if the object in question is a famous,

high profile monument this adds an extra

dimension of pressure to any conservation

works, especially if there is intense public and

media interest.

Dichloromethane (DCM) worked

successfully with ghosting in most cases but

DCM was banned from use outside industrial

installations under EU REACH (Registration,

Evaluation, Authorisation and restriction of

Chemicals) regulations in 2012. Other solvent

poultices have since become available but

their performance is mixed. In some cases wet

abrasion using a low-pressure system such as

TORC can be effective against ghosting.

Removal of paint-based graffiti from a

bronze statue is relatively simple provided it

is done promptly. Steam is usually the first

method attempted but there is also an array

of solvents which can be tried without fear

of affecting the underlying patina. Unlike

varnish layers on paintings, it is not necessary

to worry about removing one material

without dissolving another. However, the

aftermath of graffiti left on for months at a

time is usually more challenging.

Often, the drying agents or binding

agents in paint contain an acidic component

and if the graffiti is left on for a period of

time, this will etch the patina. This means

that although the paint can be removed,

the underlying patina is lightened in the

exact pattern of the graffiti. In this case, a

conservator will try to blend out the damage

using re-patination in a very localised way.

This is an over-patination technique where

the lightened colour is used as a foundation.

Increasing the depth of colour without

overpowering one area can take as much time

as patinating a large area as it involves very

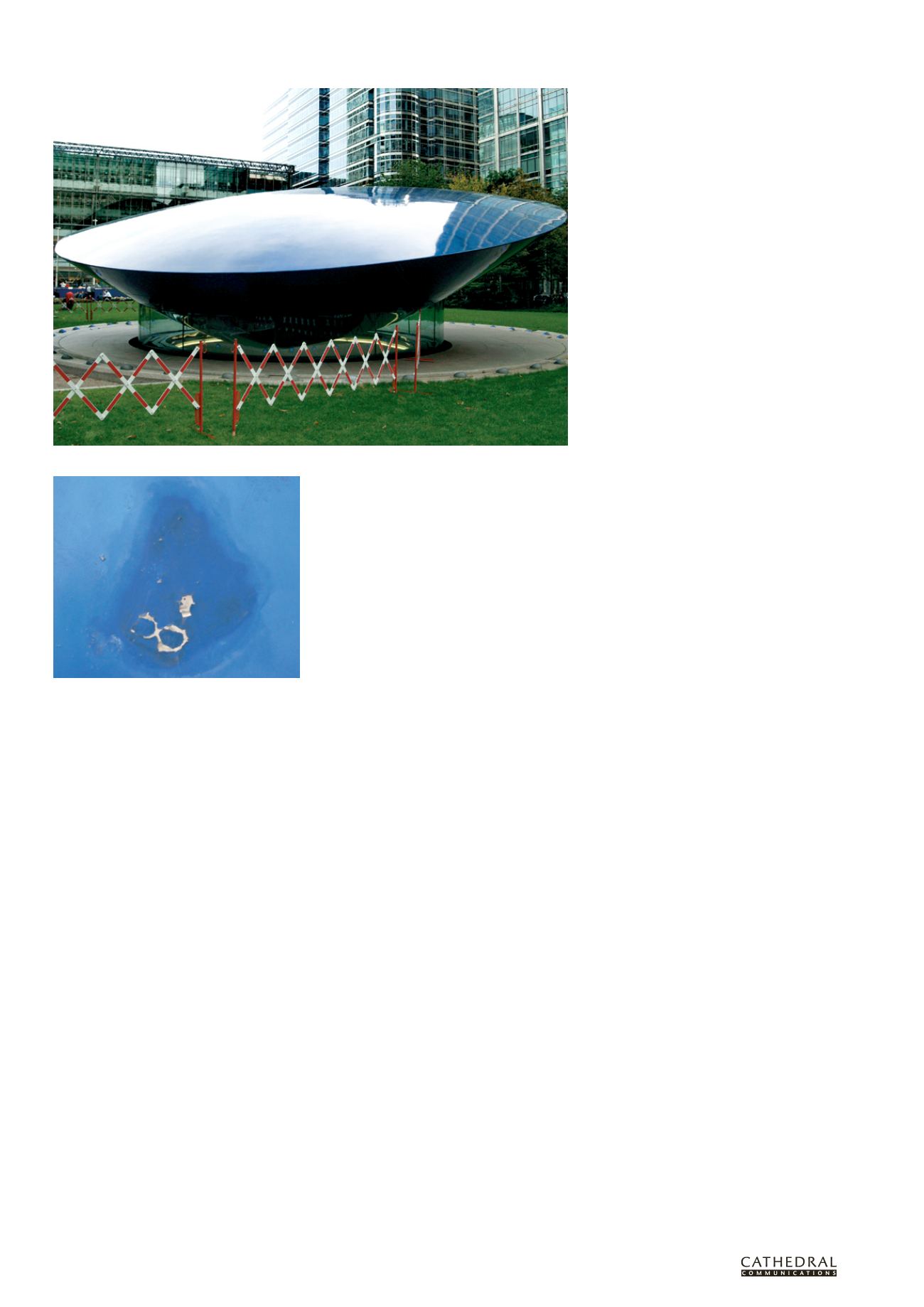

‘Big Blue’ by Ron Arad, Canary Wharf, London and, below, surface damage caused by football fans