10

BCD SPECIAL REPORT ON

HISTORIC CHURCHES

21ST ANNUAL EDITION

PROTECTIVE GLAZING

Tobit Curteis and Naomi Luxford

D

ESPITE ITS

fragile and brittle nature,

stained glass has survived in many

churches and cathedrals from as early

as the 12th century. Often it is the last vestige

of the rich colourful decoration that covered

walls, fittings and furnishings in the medieval

church interior, and early examples are of

huge significance. Unlike other works of art,

stained glass also forms an integral part of

the structure and envelope of the building.

As such, it is of particular importance that

stained glass of all periods should be conserved

in situ wherever possible, an approach which

often requires the use of protective glazing.

As part of an initiative to improve the

understanding of protective glazing systems,

a detailed research project commissioned by

the Building Conservation and Research Team

at English Heritage is currently under way.

DETERIORATION

Seen from a distance inside a church, historic

stained glass can look remarkably well preserved.

However, distance and transmitted light often

disguise problems which are only apparent

on much closer inspection. Medieval stained

glass, and some later painted decoration, are

often chemically unstable as a result of the

materials and techniques used to create them. In

particular, the leaching of potassium and sodium

ions from the glass in the presence of water can

cause severe physical deterioration of the glass

body. Stained glass windows are also subjected

to wind-loading which can damage the entire

structure. The risk of vandalism and deliberate

damage add further weight to the arguments

for protecting the exterior face in particular.

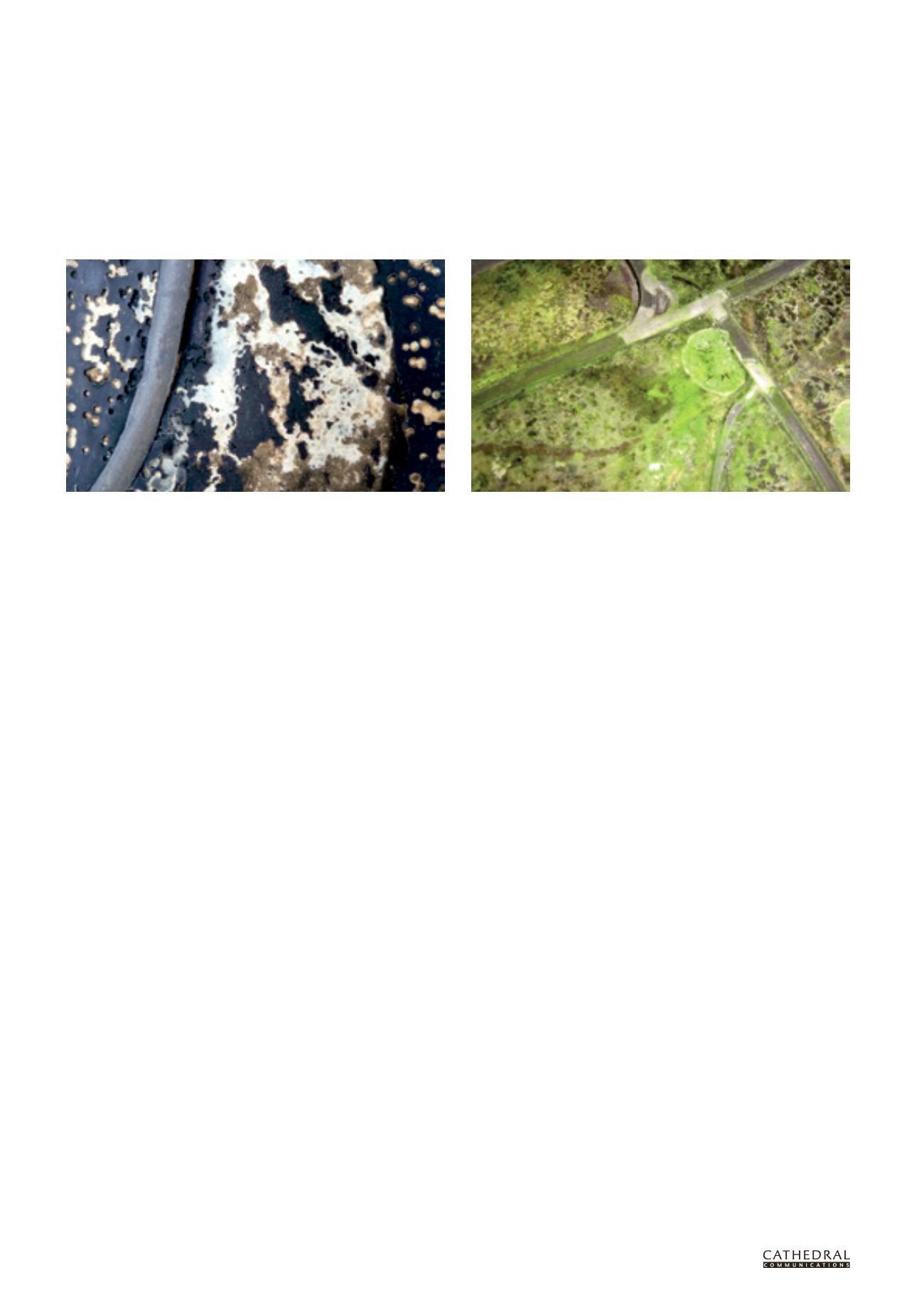

In addition, the internal face can

be damaged by repeated high levels of

condensation, which facilitate the dissolution

of soluble compounds within the glass paint

and body causing pitting. Differential thermal

stresses can lead to delamination of paint and

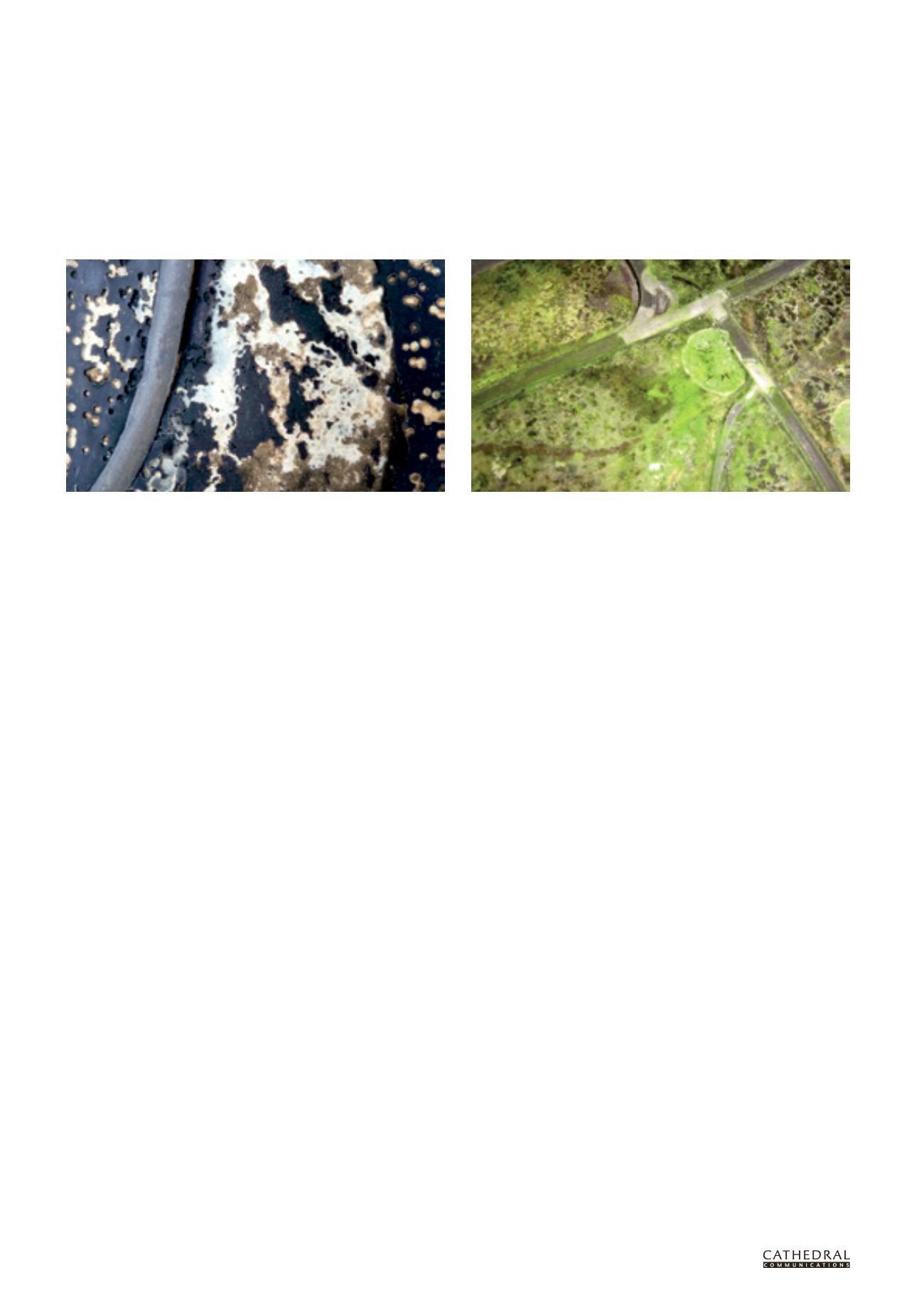

enamel layers. High levels of condensation

can also lead to substantial microbiological

growth on the surface of the glass. Not only

can this growth be disfiguring but it can

also retain moisture and the physical and

chemical side-effects of the lifecycle of the

organisms can cause further damage.

OPTIONS FOR PROTECTION

Although there are a number of ways of

protecting stained glass from physical

damage and vandalism, for example the

use of wire mesh, the only system which

can control chemical and environmental

deterioration in situ is protective glazing.

Protective glazing has a long history:

it was used at York Minster from 1856 and

Lindena church in Germany from as early as

1796. However, the benefits of this approach

were first recorded during the 1960s in Bern

Minster in Switzerland, where some of the

stained glass had been reinstalled in frames

behind new glazing after the war. These

were in noticeably better condition than

the panels that had been reinstalled in their

original positions, which were unprotected.

Protective glazing is now widely used to

conserve important and vulnerable stained

glass. However, just as no two windows or

churches are the same, no two protective

glazing systems are the same. As a result

it has been difficult to determine the best

design features for specific installations.

CURRENT PRACTICE

Protective glazing involves the installation of a

layer of new glass on the exterior of the window.

In some cases the historic glass is left in situ,

while in others it is moved forward (towards the

interior) on a metal support with the new glazing

installed in the original grooves in the tracery.

In most cases the gap between the original

glass and the protective glazing is ventilated at

the top and bottom, which allows air to pass

through the interspace between the two. Some

systems are vented to the outside (externally

ventilated), some to the inside (internally

ventilated) and some combine the two.

In some cases sealed units that are more

similar to double glazing have been used.

However, due to the difficulty in creating

an effective seal, significant condensation

can occur and this approach is now rare.

Most current protective glazing is internally

ventilated, allowing the historic glass to

be surrounded by air from within the

building, which also, generally, has the

advantage of lower levels of pollution.

AESTHETICS

One of the main concerns with the use of

protective glazing is its impact on the appearance

of the building. A wide variety of approaches

can be considered to modify the external

appearance of the protective glazing, including

glass type, glass surface treatment, and whether

the glazing is constructed in panels or is leaded

to imitate the original glass and mounting.

However, change in appearance is nothing

new. Corroding 20th-century metal mesh is

often tolerated because it appears always to have

been there. Increasing opacity and distortion

of the original glass is tolerated because it

occurs gradually. However, both cause at least

the same level of visual impact as protective

glazing when viewed externally. Internally,

the shadows cast by grilles are particularly

damaging to the appreciation of works of art.

PREVIOUS RESEARCH

Over the past 40 years research has been

carried out, mostly in France and Germany,

into the efficacy of different protective glazing

systems. Between 2002 and 2005 an EU-funded

project (VIDRIO) studied protective glazing

in a number of churches and cathedrals across

Europe. This project looked at how windows

were ventilated, the amount and duration of

condensation periods, pollution levels within

The effects of moisture: left, pitting caused by the dissolution of soluble components (Photo: Tobit Curteis Associates) and, right, microbiological growth (Photo: Holy Well Glass)